Written by James Balzer

Introduction

The nexus between climate change and water security provides a unique challenge for policy around climate resilience in the 21st century. In particular, the underlying fragilities and determinants for resilience infer the likelihood of sustained stability and prosperity, or lack thereof, in the Anthropocene (Velasco et. al, 2018). Notably, the European, Middle East and North Africa (EMENA) regions face multidimensional influences underpinning the extent of their climate security (King & Lehanne, 2021). These dimensions include inequality, judicial inefficacy, social incohesion, vulnerability to natural disasters, lack of provision of basic services and microeconomic insecurity (see Boer et. al, 2016). The present threat of climate change on EMENA’s water supply demonstrates these vulnerabilities, and has implications for EU foreign policy.

According to the IMCCS (2020) water scarcity and the lack of sustainable water management are already having significant negative effects on both agriculture and drinking water in the Middle East and Africa. The World Bank is spending $1.5 billion to fight climate change in the region, and estimates 80-100 million people will be exposed to water stress by 2025 (Broom, 2019).

The EU, being the wealthiest power in the region, should consider inter-governmental collaboration opportunities as a mitigant to climate-induced regional instability, as well as the long-term implications of such for its foreign policies, especially including aid provision. This is to bolster capacity building across EMENA; achieved through various means.

The Syrian Civil War as a Pretext

The enduring civil unrest in Syria was arguably instigated by water insecurity (Femia & Werrell, 2012). The drought from 2007-2010 was driven by a long-term warming trend in the Eastern Mediterrenean, exacerbating existing vulnerabilities across Syrian society. This, compounded by discriminatory water policies under the Assad regime, caused widespread disgruntlement, hence being an instigator for civil conflict (King & Lehanne, 2021). The near future presents increased severity in drought and water stress, conjoined with transboundary water conflict and politics. This has adverse implications for regional stability and security (King & Lehanne, 2021; Kelley et. al, 2015).

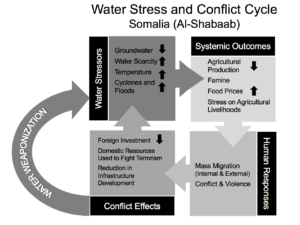

This discussion contributes to speculation of the nexus between water and security across the broader EMENA region (King & Lehanne, 2021; National Intelligence Council, 2020). Figure 1 presents the ‘water-conflict’ cycle, which King (2019) believes also contributed to water-stress induced conflict in Iraq, Nigeria and Somalia.

Figure 1 – Water-Conflict Cycle, proposing causal pathways for conflict due to water stress Source: King & Lehanne, 2021

The impact of climate change on food supply, both local and imported, also poses significant threats to climate security. In 2010-2011, a ‘once-in-a-century’ winter drought in China led to a global wheat shortage, with a huge spike in global wheat prices, including exorbitant bread price increases in Egypt, the world’s largest wheat importer (Sternberg, 2012). Certain commentators believe this demonstrated ‘hazard globalisation’, becoming an instigator for accentuating underlying disgruntlement in Egypt, hence contributing to the socio-political upheaval that was the Arab Spring (see Revi et. al, 2014; Femia & Werrell, 2013).

This demonstrates the vulnerabilities of global food systems, with elongated supply chains and a ‘just-in-time’ model for distribution, especially in countries without appropriate reserves and sovereign food production capacities (Clapp & Moseley, 2020). Contemporary food systems are “within a system driven by economic growth and risk-averse, efficiency-oriented practices” (Rogers et. al, 2020 p. 4). The EU needs to observe this trend, and incorporate such into their long-term foreign policy, so as to mitigate adverse flow-on effects for the EU. Flow-on effects from water insecurity include migration crises, conflict over resource scarcity and dynamic exacerbations in existing inadequacies in societal governance and functionality (Galgano, 2019; IMCCS, 2020).

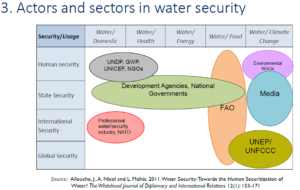

Additionally, Figure 2 indicates the varied facets of water security related conflict, and the diverse range of actors involved in addressing such. The breadth and depth indicated by this highlights the need for expeditious and targeted action, addressing root causes with far reaching impacts (see Allouche et. al, 2011).

Figure 2 – The various typologies of water security, and actors involved

Source: Allouche et. al (2011)

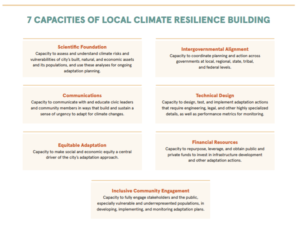

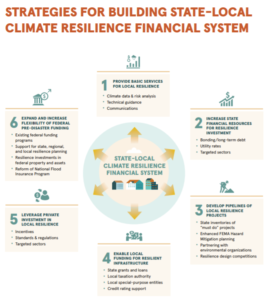

Furthermore, Figure 3 and 4 demonstrate the dimensions of climate resilience foreign aid and climate financing should target, in order to address root cause dimensions to complicated problems. Plastrik et. al (2020) strongly reinforces this notion.

Figure 3 – The 7 Capacities of Local Climate Resilience Building

Source: Plastrik et. al (2020)

Figure 4 – Strategies for Building State-Local Climate Resilience Financial System Source: Plastrik et. al (2020)

The Role of the EU: Financial Means of Addressing Vulnerabilities?

The EU needs to consider the broader engenderment of climate-water insecurity nexus into their longer-term foreign policy. The aforementioned dimensions of state-local climate resilience provide a possible framework by which they may seek to do so. Regional conflicts and possible climate refugee crises may derive from multifaceted dimensions of resource scarcity across the EMENA region (King & Lehanne, 2021; Oxfam, 2019). As seen in the refugee crisis of 2015, arguably instigated by the climate-water insecurity nexus, this has long reaching socio-political implications, and shapes EU foreign policy in various ways (see Kelley et. al, 2015; Bennett, 2015). Rather than be reactive to this emergent threat, the EU ought to consider more proactive approaches to mitigating this risk.

Climate resilience depends on an amalgamation of various dimensions of resources, purposes and mechanisms, possibly derived from public and private funds at all scales. In some contexts, the EU public sector can take responsibility, but in others, the EU private sector, including the EIB and ECB, may be the most beneficial actors (see Plastrik et. al, 2020). Figure 4 demonstrates the ‘7 capacities’ of climate resilience that municipalities should engender through climate resilience financing.

Additionally, MENA countries have policies and structures to collect revenue and invest in public infrastructure, support local governments, drive private investment, and leverage other public funding opportunities. Despite this, many jurisdictions in this region do not have strategies and resources to achieve climate resilience strengthening, nor have they been reinforced with extra revenue that will be needed (Plastrik et. al, 2020). In addition, there are some significant funding gaps due to some emergent necessities of resilience building (Plastrik et. al, 2020). Figure 5 highlights 6 strategies for ‘state-local’ climate resilience financial systems, which can be leveraged by governments to engender climate resilience, and therefore, security.

In an interview with Dr Peter Mollinga, from SOAS University of London, discussion and insights around the role of political instability in relation to the climate-water insecurity nexus were gleaned. As Dr Mollinga stated, “that question assumes there is political insecurity associated with climate change…I think we need to be very careful by what we mean by that”. He further went on to say “attributing cause with climate change in a material sense to particular events at particular times…I think the attribution of cause is particularly difficult”.

This brings into question the exact scope of climate resilience financing, and how a misguided understanding of cause-effect relations can lead to ineffective, wrongly focused policy measures. This is also regarding matters such as governance and management of climate change related threats, including aversion to ‘top-down’ financing, especially from international sources and traditional aid providers (Leichenko, 2011). This includes ‘bottom-up’ decision making and innovation, including through the lens of ‘experiments’ for adaptation and resilience, hence acknowledging central government and aid bodies themselves cannot be the primary solution providers, and are sometimes at the core of the problem. Accordingly, Boyd & Juhola (2014) emphasise polycentric, multi-scalar and adaptive governance through multiple actors in different settings. Additionally, siloed technological, ecological and political solutions are largely ineffective, and hence, systems thinking needs to be a key outcome from climate financing (Boyd & Juhola, 2014). This avoids the misattribution of causal relationships, and therefore guides effective policy.

Reinforcing this sentiment, Dr Mollinga questioned the possible efficacy of ‘technical fixes’ in foreign aid and development, citing “we all like technical fixes, and we all like to believe, very desperately, that wouldn’t it be nice if we had a technical fix…such a seductive thought…but if you honestly look at the literature of development discourse…then you cannot say this is a simple matter”. Regarding overall governance processes for climate-water security, he claimed “we like to simplify, and thereby overrate the strength of the connection…I think the weakness is…we don’t have two things: most of these approaches have been statist, or top-down…and we’ve very little involvement in governance processes”. Water is hence locked in nationalist and transboundary stiflement and conflict, meaning deeper geopolitical problems could be much harder for EU foreign policy to address. We are also “stuck in a statist development” pattern, depending on top-down public sector driven foreign policy and resilience engenderment, with highly varied success. Furthermore, complementing the argument of Leichenko (2011) and Boyd & Juhola (2014), Dr Mollinga believes it is important to understand markets as “social relations”, that when understood, allows development actors to properly “frame” these investment processes.

Hence, the EU needs to consider what avenues it might seek to achieve in pursuing regional climate security through the lens of water security. It may be plausible for the EU to use more private sector investment vehicles, including possibly through the EIB and ECB. This could finance equity and debt finance climate resilience projects through different instruments, and hence be innovative in its provision of climate-water security across EMENA. Conversely, there is notable concern towards the use of private capital, and there has been a growing contestation and aversion to the use of it in the space of water security. Additionally, as suggested by Dr Mollinga, simple hypotheses of causal relationships cannot guide any EU foreign policy seeking to address the often propagated climate- water security nexus. Instead, well scoped and implemented aid must be at the core of effective EU climate resilience financing.

Conclusion

Climate change is an internationally recognised threat to stability, prosperity and security. Hence, it will guide regional and national foreign policy, especially in the realm of geostrategy. Discourse suggests the climate-water security nexus is pertinent in the EMENA region, and accentuates existing vulnerabilities, while leading to adverse and multi-dimensional flow-on effects. Climate Change related drought allegedly contributed to the Syrian civil war and subsequent refugee crisis of 2015. Likewise, the Arab Spring of 2011 was arguably instigated by climate change related drought, not just in the MENA region, but also in China.

Therefore, the EU should preemptively develop long term regional security strategies in alignment with this propagated reality. However, there is contention over the extent of attribution water crises have on regional security and conflict, and also its causes and solutions. Therefore, the EU must consider in-depth evaluation and assessment of causal pathways and attributions before developing this long-term strategy. This is both regarding the problem and the solution, therefore having correctly targeted financing strategies.

Reference List

Allouche, J., Nicol, A., & Mehta, L. (2011). Water Security: Towards the Human Securitisation of Water?. The Whitehead Journal of Diplomacy and International Relations, 12(1), 153-171.

Bennett, C. (2015, September 7). Failure to act on climate change means an even bigger refugee crisis. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2015/sep/07/climate-change-global-warming-refugee-crisis.

Boer, J., Muggah, R., & Patel, R. (2016). Conceptualising City Fragility and Resilience. United Nations University Centre for Policy Research. https://ocw.tudelft.nl/wp-content/uploads/2Conceptualising-city-fragility-and-resilience.pdf.

Boyd, E., & Juhola, S. (2014). Adaptive climate change governance for urban resilience. Urban Studies, 52(7), 1234-1264.

Broom, D. (2019, April 5). How the Middle East is suffering on the front lines of climate change. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/04/middle-east-front-lines-climate-change-mena/.

Clapp, J., & Moseley, W. (2020). This food crisis is different: COVID-19 and the fragility of the neoliberal food security order. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 47(7), 1393-1417.

Femia, F., & Werrell, C. (2013). Syria: Climate Change, Drought and Social Unrest. The Center for Climate and Security. https://climateandsecurity.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/syria-climate-change-drought-and-social-unrest_briefer-11.pdf.

Galgano, F. (2019). The Environment-Conflict Nexus: Climate Change and the Emergent National Security Landscape, Springer.

International Military Council on Climate and Security (IMCCS) (2020). The World Climate and Security Report 2020.

Leichenko, R. (2011). Climate change and urban resilience. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 3(3). 164-168.

Kelley, C., Mohtadi, S., Cane, M., Seager, R., & Kushnir, Y. (2015). Climate change in the Fertile Crescent and implications of the recent Syrian drought. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 11(112), 3241-3246.

King, M., & Lehanne, R. (2021, April 30). Drought is leading to instability and water weaponization in the Middle East and North Africa. The Center for Climate and Security. https://climateandsecurity.org/2021/04/drought-is-leading-to-instability-and-water-weaponization-in-the-middle-east-and-north-africa/.

King, M. (2019). Dying for a Drink. American Scientist. 107(5), 296-298.

Muller, M. (2007). Adapting to Climate Change: Water Management for Urban Resilience. Environment and Urbanization, 19(1), 99-113.

National Intelligence Council (2020, July 10). Water Insecurity Threatening Global Economic Growth, Political Stability. https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/2020-Nov-NIC-Memo-re-Water-Insecurity-Final.pdf.

Oxfam (2019, December 2). Forced From Home: Climate-fuelled Displacement. https://oxfamilibrary.openrepository.com/bitstream/handle/10546/620914/mb-climate-displacement-cop25-021219-en.pdf.

Plastrik, P., Coffee, J., Bernstein, S., & Cleveland, J. (2020). How State Governments Can Help Communities Invest in Climate Resilience. The Summit Foundation. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5736713fb654f9749a4f13d8/t/5f80e0ee6c7e12422ef0793e/1602281714556/Plastrik+Coffee+State+Resilience+Investment+Framework+2020.pd

Revi, A., Satterthwaite, D., Aragón-Durand, F., Corfee-Morlot., J., Kiunsi, R., Pelling, M., Roberts, D., Solecki, W. (2014). Urban Areas in Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability, Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/275035197_Urban_Areas_in_Climate_Change_2014_Impacts_Adaptation_and_Vulnerability_Part_A_Global_and_Sectoral_Aspects_Contribution_of_Working_Group_II_to_the_Fifth_Assessment_Report_of_the_Intergovernmental_Pane

Rogers, P., Bohland, J. and Lawrence, J. (2020). Resilience and Values: Global perspectives on the values and worldviews underpinning the resilience concept. Political Geography, 83(n.a.), 1-9.

Sternberg, T. (2012). Chinese Drought, Bread and the Arab Spring. Applied Geography, 34(n.a.), 519-524.

Velasco, M., Russo, B., Martinez., M., & Malgrat, P. (2018). Resilience to cope with climate change in urban areas – A Multisectorial approach Focusing on Water – The RESCCUE Project. Water. 10(10). 1356-1367.

The ’Ndrangheta’s Infiltration and Threat to European Institutions

The ’Ndrangheta’s Infiltration and Threat to European Institutions  From Paper to Practice: How Grassroots Norms Undermine Gender Rights in Pakistan

From Paper to Practice: How Grassroots Norms Undermine Gender Rights in Pakistan  Exploited Childhoods: The Role of Global Corporations in Perpetuating and Mitigating Child Labour

Exploited Childhoods: The Role of Global Corporations in Perpetuating and Mitigating Child Labour  Human Rights Challenges in Addressing SLAPPs in Media, NGOs and Journalism in the EU

Human Rights Challenges in Addressing SLAPPs in Media, NGOs and Journalism in the EU