Written by Vasilis Psarras

In the 2021 Eurobarometer, 80 percent of respondents thought that the euro is a good thing for the EU, reaching a new high rate of approval (Eurobarometer, 2021). The introduction of the common currency twenty years ago, in January 2002, was a clear example of political and economic integration, which so far seems like a success in people’s minds. In order to understand the necessity of the euro and the European Monetary Union (EMU), we must first go back to 1979 when the Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) was established by the European authorities, which defined a range for the exchange rate of the members of the European Economic Community (EEC). This fixed exchange rate regime was the cause of great speculative movements as it was mentioned by Buiter, Corsetti & Pesenti (1998), due to the continuous policies of “sterilization” followed by the monetary authorities, in which mainly the Bundesbank intervened directly in the exchange market in order to keep domestic money supply stable. Because of the policy mix followed by Germany in 1992 after its unification and the speculative attacks of 1992 in European currencies the ERM collapsed, creating currency crises in all its members (Buiter, Corsetti & Pesenti, 1998).

European leaders noticed that this monetary system was unsustainable and systemically dangerous, which is why they had laid the foundations for the monetary unification introduced by the Maastricht Treaty in 1992. The third and final stage of EMU stipulated that a single currency should have been created by 1 January 1999 at the latest, when the euro was given in the book-entry form. It is reasonable that the introduction of the single currency has collectively helped the transactions between citizens within the member-states of the Eurozone and has boosted trade (Babalioutas and Mitsopoulos, 2014, p.108-19). Babalioutas and Mitsopoulos (2014, p. 108-19) mentioned that the opportunity provided by the freedom of movement of capital, goods, and people was sealed by the introduction of the common currency, which eliminated any exchange costs that previously existed between countries and greatly facilitated trade

Alongside the primary advantage of the freedom of movement of goods thanks to the common currency, it is also worth noticing the effectiveness of conducting monetary policy. Although the monetary authorities of the euro area member states gave up the national sovereignty they had before EMU, the objective of the European Central Bank (ECB) makes monetary policy particularly effective and consistent. As it was mentioned by Ilzetzki, Reinhart & Rogoff (2017) until 2008 the ECB pursued a Taylor-style policy rule, a monetary policy rule explaining how interest rates derive from fluctuations in the output and inflation, as an extension of the regime of the German Bundesbank, which has always followed tough monetary practices to keep inflation low. For countries such as Greece, which in the past had experienced strong inflationary pressures and in the early 1980s had the finance minister appointed also as the Central Banker, the introduction of the EMU and its commitment created a safer monetary environment and improved its monetary policy (Alogoskoufis, 2021).

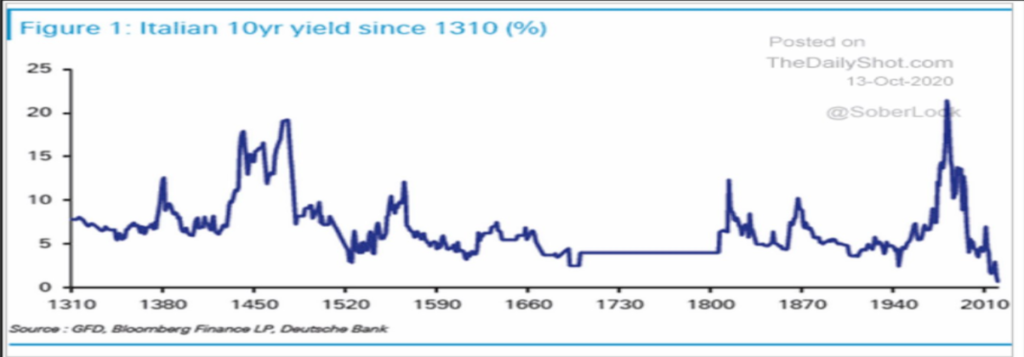

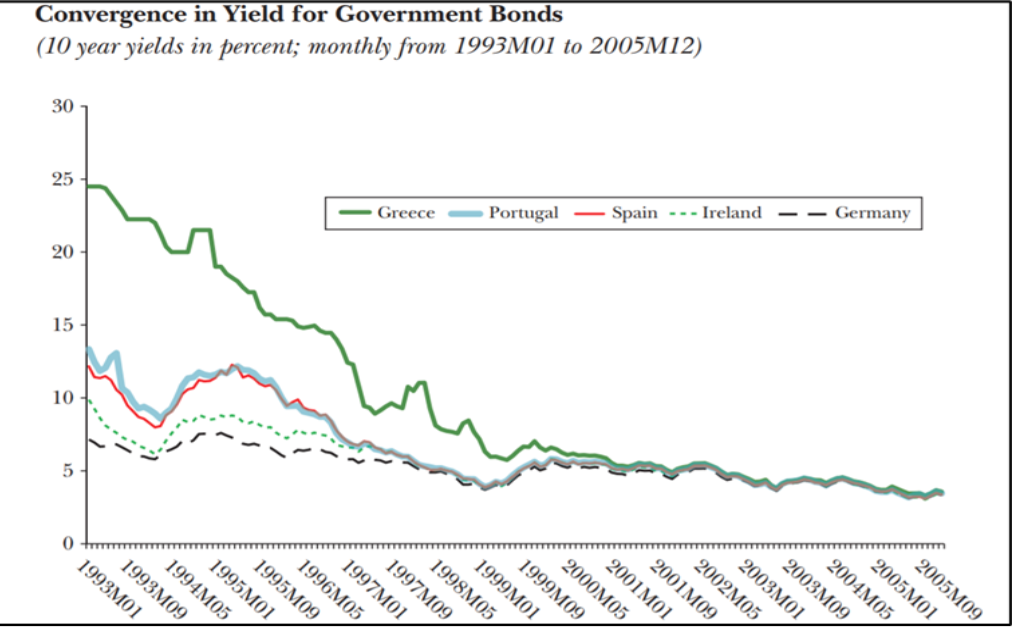

In addition, the common currency has accomplished to bring down interest rates in the banking sector and bond yields of the Eurozone countries to unprecedented levels, thus providing member states with opportunities for more effective fiscal and structural policies. As it is shown in Figure 1, no Italian public body in the last 700 years has been able to issue 10-year bonds with such low yields as those achieved by the euro. Apart from the case of Italy, however, we see from Figure 2, deriving from Fernadez-Villaverde, Garicano & Santos (2013), that after the implementation of the Maastricht Treaty, the yields of 10-year bonds of 4 countries that entered bailouts in 2010 began to decline significantly, while with the implementation of the euro they fully converged with German bond yields.

Figure 1

Despite the effective and successful convergence of interest rates of the Eurozone member states seen over the last 20 years, the euro has created many structural and institutional divergences mainly in the productivity and competitiveness of member states. It is estimated by Eggertsson, Ferrero & Raffo (2013) that the real exchange rate in Greece appreciated by 10% in the first five years of widespread circulation of the euro, automatically making the Greek economy 10% less competitive vis-à-vis Germany and France. Many analysts in recent years have expressed their doubts about a two-speed euro, which we see has made periphery economies less competitive than those of the core (Kudera, 2019).

Figure 2

The single currency not only causes economic divergence, but it also simultaneously prohibited the authorities of the Eurozone member states to implement exchange rate policies to absorb possible shocks caused to the economy. Milton Friedman, who had long been an advocate of flexible exchange rates, said that monetary integration would create political problems for the Eurozone as its countries would not be able to respond to asymmetric shock with the implementation of monetary devaluation (Friedman, 1997). In the case of the single currency, the authorities of the countries can implement policies of internal devaluation or appreciation of wages, but these policies can be particularly difficult to implement because of the conditions in the labour market and harmful to citizens, due to falling pressures on wages (Krugman, 2012).

Milton Friedman has always been a supporter of flexible exchange rates and it was reasonable to oppose the proposal to introduce the euro, but I think that even if Keynes was alive, who was opposed to the gold standard followed by countries until 1930 he would disagree with the creation of a single economic zone in Europe. The architecture of the monetary union was built on Mundell’s (1961) proposal for the creation of Optimum Currency Areas (OCA), but the Eurozone is an example of an imperfect currency zone, as we have not succeeded in creating a single fiscal authority and moreover, we have not reached the optimal levels of capital and labour mobility (Krugman, 2012).

Finally, it is worth noting that apart from the structural weakness of the monetary union, the common currency project has inherent institutional weaknesses. As it was mentioned by Pistor (2020) the recent example of the decision of the German Constitutional Court to declare as “illegal” the policies of buying government bonds on the part of the ECB raises basic questions about the legality of these policies, their consistency, and the sustainability of the euro itself. Let us remember as Pistor (2020) points out, the case where a member of the Governing Council of the ECB, the Governor of the Bundesbank, Jens Weidmann, testified in this case against the legitimacy of these policies, thereby demonstrating the fundamental lack of credibility and sustainability of the monetary union.

This year we commemorate 20 years of the euro in circulation and this article tries to provide some of the benefits and drawbacks of the common currency. There are great challenges ahead for Eurozone policymakers with the most important one being increasing inflation and normalisation of monetary policy alongside the fear of future recession because of war in Ukraine. Despite the flaws and fragmentations of the currency union, the euro remains a tool of political, social, and economic necessity, and recalling Draghi’s famous remark “we are going to do whatever it takes to save the euro…and believe me it will be enough”.

References

Image credits: ECB Instagram Account

The ’Ndrangheta’s Infiltration and Threat to European Institutions

The ’Ndrangheta’s Infiltration and Threat to European Institutions  From Paper to Practice: How Grassroots Norms Undermine Gender Rights in Pakistan

From Paper to Practice: How Grassroots Norms Undermine Gender Rights in Pakistan  Exploited Childhoods: The Role of Global Corporations in Perpetuating and Mitigating Child Labour

Exploited Childhoods: The Role of Global Corporations in Perpetuating and Mitigating Child Labour  Human Rights Challenges in Addressing SLAPPs in Media, NGOs and Journalism in the EU

Human Rights Challenges in Addressing SLAPPs in Media, NGOs and Journalism in the EU