Written by: Martina Llobell González-Gallarza

Edited by: Martina Canesi

Keywords: rule of law, conditionality, Hungary, EU governance, cohesion funds, democratic backsliding

1. Introduction

The European Union underwent significant expansion through the 2004 enlargement process, which integrated multiple Central and Eastern European nations. While this historic moment marked a major step toward the reunification of Europe, it also introduced long-term challenges regarding institutional convergence and democratic resilience in post-communist states (Grabbe, 2006).

This paper investigates to what extent the activation of the rule of law conditionality mechanism succeeded in addressing the systemic risks to the EU budget arising from institutional degradation in Hungary.

2. Definition of key terms

Firstly, the concept of rule of law is understood as a structure of government in which all entities, including the State itself, are subject to recognized and codified laws that are enacted and enforced by established processes (O’Neil, 2022). According to the European Commission, the concept of rule of law is defined by six principles: legality, legal certainty, prohibition of the arbitrary exercise of executive power, effective judicial protection, separation of powers, and equality before the law (European Commission, n.d.).

Secondly, the idea of a conditionality mechanism is presented in the Rule of Law Conditionality Regulation (EU, Euratom) 2020/2092, by the European Parliament and Commission, under point no. 2, which affirmed that the Union’s financial interests must be protected in accordance with the values enshrined in Article 2 TEU. In practice, this means that financial support from the Union is conditional upon compliance with foundational democratic and legal standards (European Parliament & Council2020). Regulation (EU, Euratom) 2020/2092).

Thirdly, the term systemic risk, in the context of EU financial governance, refers to institutional failures—such as non-control of corruption, lack of judicial independence, or compromised public procurement—which undermine the EU’s ability to ensure that its funds are being used rightfully and legally. This risk must be sufficiently direct and demonstrable to justify the suspension of funding (Regulation 2020/2092, Article 4).

3. Methodological approach

This paper follows a mixed analytical framework, combining legal and political document analysis with quantitative governance data. The qualitative data relies on the interpretation of EU legal texts, European Council conclusions, and academic literature on democratic backsliding and conditionality. These documents span from 2013 to 2024, covering the evolution of the rule of law debate and the adoption of Regulation 2020/2092. The academic literature consulted includes both foundational theoretical texts and the most recent contributions on democratic backsliding, compliance models, and EU enforcement mechanisms Quantitative data is selected from the Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) developed by the World Bank in 2023, where three indicators are chosen for comparison: rule of law, control of corruption, and government effectiveness. Hungary’s scores are compared to those of Germany, Czech Republic and Poland. These three indicators were selected because they directly reflect a government’s capacity to uphold legal norms, ensure transparency in public spending, and manage EU funds responsibly.

This table serves to support the argument that the risk of misuse of the EU budget is not incidental but structural and provides measurable evidence of a systemic risk posed by Hungary.

4. Background of the problem

Viktor Orbán, the current Prime Minister of Hungary, rose to power in 2010 through the Fidesz party and has since promoted a model of “illiberal democracy” – a coherent ideological backlash against liberal values, promoting majoritarianism, nationalism, and cultural homogeneity under the guise of democratic legitimacy (Laruelle, 2022). Hungary’s internal transformation has triggered increasing concern from EU institutions.

Hungary represents a new challenge for the EU that was not considered in 2004: the democratic erosion of a member state, with potential ripple effects on other member states and the credibility of its external conditionality. In 2022, the European Parliament declared that the country could no longer be considered a democracy, due to corruption, lack of judicial independence, absence of transparency, and attacks on press and academic freedom (European Parliament, 2022).

Orbán defends his political course by asserting that Hungary’s national interests take precedence over supranational EU norms—a stance that lies at the heart of the ongoing legitimacy crisis within the Union (Kelemen, 2020).

5. Theoretical foundations of conditionality and compliance

5.1. Compliance and conditionality models

Scholars have identified two main approaches to interpreting member states’ non compliance with rules: the enforcement approach, which advocates sanctions for involuntary breaches and management approach, which sees violations as strategic and favors dialogue (Czina, 2024). In line with the latter, Priebus (2022) argues that budgetary conditionality is largely ineffective against deliberate political decisions, as in Hungary’s case.

Blauberger and van Hüllen (2021) argue that the creation of this mechanism was an opportunity to reinforce, at least at a symbolic level, the Commission’s credibility after the failure to apply Article 7. Hungary’s case illustrates the challenges of applying the conditionality mechanism to a full member state, where noncompliance is deliberate rather than accidental.

5.2. Why rule of law matters

Why is respect for the rule of law essential within member states’ domestic policies? Several scholars have demonstrated its necessity for the EU’s proper functioning:

- Kochenov’s (2019) argues that the breakdown of mutual trust undermines cooperation in the single market, judicial system, and Schengen area.

- The European Commission (2020) stresses its role in safeguarding equality and independent courts.

- Pech (2022) argues that the rule of law serves as a fundamental pillar of democratic systems.

- The EBC’s 2018 economic bulletin demonstrates that institutions like national banks depend on legal independence and rule of law for their operation.

Hence, the need for a conditionality mechanism that enforces the respect for this principle is key to preserve institutional coherence and protect the EU budget.

6. The activation of the conditionality mechanism

6.1. Origins and Political context of the conditionality mechanism

The idea of a conditionality mechanism was first proposed in the European Union in 2013, when four European foreign ministers suggested it in a letter as a “last resort” to protect the rule of law (Rutte et al., 2013). The political momentum behind the Conditionality Regulation emerged in 2018, when the European Union faced persistent obstacles in enforcing Article 7.2 TEU – “The European Council, acting by unanimity on a proposal by one third of the Member States […], may determine the existence of a serious and persistent breach by a Member State of the values referred to in Article 2,[…]”. Its requirement for unanimity in the final stage rendered it ineffective, as Hungary and Poland protected each other from sanctions (Kirst, 2021).

As a response, the EU adopted Regulation (EU, Euratom) 2020/2092, which allows for the suspension of funds if there are violations of rule of law principles that directly threaten proper management or protection of EU funds (Art. 4). However, final activation took several months as both Hungary and Poland requested its review before the European Court of Justice, arguing it infringed the EU treaties (Baranowska, 2022).

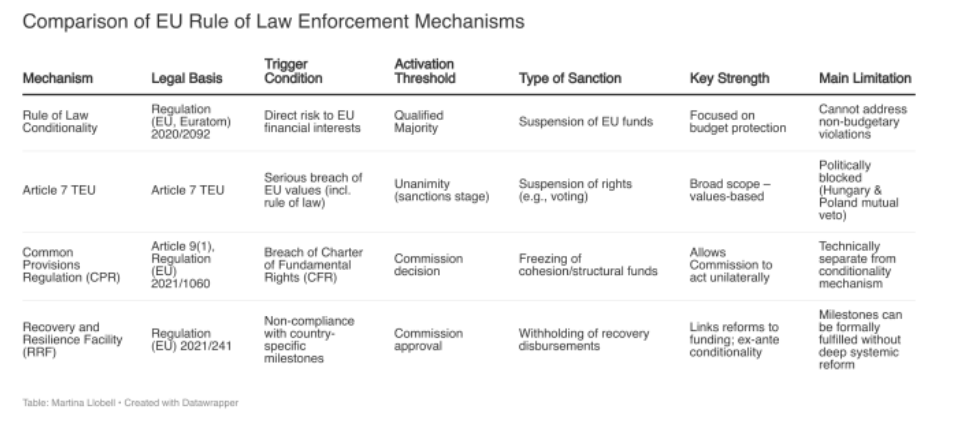

Table 3. Comparison of EU Rule of Law Enforcement Mechanisms Source: Martina Llobell González-Gallarza

6.2. Legal activation: Hungary as the first case

In April 2022, the Commission activated the mechanism against Hungary for the first time on the grounds of corruption risks and deficiencies in European budgetary implementation (Lane and Morijn, 2024). In September 2022, the Commission proposed freezing €7.5 billion, equivalent to 65% of three cohesion programs. However, in December 2022 the Council reduced the suspension to 55%, equivalent to €6.3 billion, acknowledging partial reforms made by Hungary (Csaky, 2025). This resulted in the unfreezing of €10.2 billion in cohesion funds just before the fiscal cost became effective (Csaky, 2025). This strategic shift occurred at a time when the Commission needed Hungary’s vote (2023) to approve aid to Ukraine. Faced with the possibility of a Hungarian veto, the Union allowed the unfreezing of certain funds (Lane and Morijn, 2024).

In fall 2022, the Commission evaluated Hungary’s anti-corruption reforms and found them insufficient to justify unfreezing the funds. While the Council acknowledged some progress by reducing the suspension, this partial recognition raised questions about whether the measures truly addressed the underlying rule of law concerns (Lane and Morijn, 2024). As of February 2025, €19 billion remains frozen — which represents 10.7% of Hungary’s GDP (Csaky, 2025).

This episode of geopolitical bargaining between Hungary and the European Union illustrates that Hungary wields more leverage than commonly assumed. While the rule of law mechanism is legally enforceable, it remains susceptible to political trade-offs that can significantly weaken its intended deterrent effect. Moreover, the UE has complementary tools for the enforcement of conditionality measures. On the one hand, the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) that introduces the concept of “milestones”, of which 27 were established in 2022 for Hungary and whose fulfillment is a requirement for the release of any fund (Csaky, 2025). On the other hand, the Common Provisions Regulation (CPR) governs the management of cohesion funds and allows the Commission to act unilaterally when freezing and unfreezing funds (European Parliament & Council, 2021).

7. Analysis of the results

7.1. Domestic implementation and institutional evasion

Following the implementation of the conditionality mechanism Orbán implemented a set of anti-corruption and fund misappropriation laws in Hungary – largely symbolic and not functionally transformative. The reforms included (Lane & Morijn, 2024):

- A new Integrity Authority whose directing committee was appointed by a fully captured state agency;

- The creation of an Anti-Corruption Task Force, lacking independence and being effectively controlled by pro-government actors;

- The new law against public prosecution can only be activated by those with access to information that the prosecutor’s office is not required to disclose;

- Additionally, the asset declaration system only requires declaration by one member of officials’ households;

- Cooperation with OLAF — the anti-fraud EU agency — was improved on paper, but domestic oversight bodies saw their powers reduced.

According to various NGO(1) reports released in March 2023, Hungary failed to implement any meaningful reforms, with most EU-mandated conditions regarding rule of law and human rights remaining unaddressed, undermining the credibility of these promised changes (Czina, 2024).

Table 4 demonstrates Hungary’s history of veto actions, illustrating its ability to obstruct collective EU decisions. The frequency and thematic breadth of these blockages reinforce the argument that Hungary holds considerable leverage when its vote becomes pivotal in moments of geopolitical crisis.

7.2. Structural and legal constraints on EU enforcement

One of the main limitations denounced by academics in the application of the conditionality regulation is that, according to paragraph (e) of Regulation 2020/2092 the mechanism can only be triggered if a breach of Article 2 TEU has a “sufficiently direct” effect on the EU budget. Furthermore, paragraph (d) requires the Council to consider all other possible alternatives – such as Article 325(4) TFEU, CPR, or financial regulation – before resorting to conditionality (Kirst, 2021). Therefore, if a country violates European rules but not in relation to the use of funds, this conditionality system cannot be used as a weapon (Kirst, 2021).

This situation also raises the question that fund conditionality can only stop, or attempt to stop, countries whose economies depend on them and misuse them, something that while now affects Hungary, would not affect other possible cases of wealthier countries within the Union (Csaky, 2025).

Moreover, paragraph I.1(c) of the Conditionality Regulation delays the application of conditionality until the Commission has implemented guidelines, and the Court of Justice has approved – under Article 263 TFEU – the implementation of such regulations (European Union, 2008). This procedural condition delayed enforcement for nearly two years, severely undermining the Regulation’s deterrent effect and credibility.

The evidence suggests that while the regulatory framework is well-defined, its implementation has had mixed results. Hungary’s strategic approach to compliance has enabled access to certain funds through minimal reforms that meet technical requirements without addressing fundamental concerns. Furthermore, the unintended consequences of these sanctions have primarily affected Hungarian academic institutions and their stakeholders, particularly impacting participants in EU educational and research initiatives such as Erasmus+ and Horizon Europe (Czina, 2024). This reinforces the idea that a legal instrument alone is insufficient without consistent political will.

8. Conclusion

The conditionality mechanism has created strong financial leverage but faces ongoing structural constraints. While experts consider it essential for protecting EU values and integrity, its effectiveness remains limited. Through strategic diplomacy and voting power during key events, Hungary has secured partial fund access despite minimal reforms, highlighting how member states with strategic importance can leverage their position. The EU faces the challenge of developing more effective legal tools to address democratic backsliding, and its strength will rely on better safeguarding democracy within its borders.

9. Bibliography

Baranowska, G. (2022). FREEZING EU FUNDS: An Effective Tool to Enforce the Rule of Law? Max Planck Institute. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4168724

Blauberger, M., & van Hüllen, V. (2021). Responding to democratic backsliding in the EU: Supranational strategies and domestic obstacles. Journal of European Public Policy, 28(3), 369–386.

Czina, V. (2024). The Commission’s approach to rule of law backsliding: Managing instead of enforcing democratic values. In Jakab, A. & Kochenov, D. (Eds.), Enforcing the Rule of Law in the EU. EBSCOhost. https://research-ebsco com.scpo.idm.oclc.org/c/5v7is5/viewer/pdf/5sspb3rq2f?route=details

Csaky, C. (2025). Challenging Conditionality: Who Holds the Real Power—Viktor Orbán or the European Union?

European Central Bank. (2018). Economic Bulletin Issue 5. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/economic-bulletin/html/eb201805.en.html

European Commission. (n.d.). What is the rule of law? https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/policies/justice-and fundamental-rights/upholding-rule-law/rule-law/what-rule-law_en

European Commission. (2021). Rule of Law Conditionality Mechanism: Commission defends the regulation in the Court of Justice. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_21_5801

European Parliament & Council. (2020). Regulation (EU, Euratom) 2020/2092 on a general regime of conditionality for the protection of the Union budget. Official Journal of the European Union, L 433I/1. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32020R2092

European Parliament & Council. (2021). Regulation (EU) 2021/1060 laying down common provisions. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legalcontent/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32021R1060

Grabbe, H. (2006). The EU’s transformative power: Europeanization through conditionality in Central and Eastern Europe. Palgrave Macmillan.

Hughes, J., Sasse, G., & Gordon, C. (2004). Europeanisation and regionalization in the EU’s enlargement to Central and Eastern Europe: The myth of conditionality. Palgrave Macmillan.

Hughes, J., Sasse, G., & Gordon, C. (2008). EU enlargement and the failure of conditionality: Pre-accession conditionality in the fields of democracy and the rule of law. Palgrave Macmillan.

Kelemen, R. D. (2020). The European Union’s authoritarian equilibrium. Journal of European Public Policy, 27(3), 481–499.

Kochenov, D. (2008). EU Enlargement and the Failure of Conditionality. Kluwer Law International.

Kochenov, D., & Pech, L. (2015). Upholding the Rule of Law in the EU: On the Commission’s Pre-Article 7 Procedure as a Timid Step in the Right Direction. EUI Working Papers.

Kirst, N. (2021). Rule of Law Conditionality in EU Funds Regulation: The Added Value of Article 2 TEU. Common Market Law Review, 58(3), 643–668.

Laruelle, M. (2022). Illiberalism: A Conceptual Introduction. Journal of Illiberalism Studies, 1(1), 1–12.

Liboreiro, J. (2024, May 14). EU completes reform of migration rules despite Poland and Hungary voting against. Euronews. https://www.euronews.com/my europe/2024/05/14/eu-completes-reform-of-migration-rules-despite-poland-and hungary-voting-against

O’Neil, S. (2022). Foundations of Comparative Politics. Oxford University Press.

Priebus, S. (2022). The Commission’s response to Hungary’s rule of law violations: Symbolic politics or substantive enforcement? European Constitutional Law Review, 18(2), 203–228.

Rutte, M., Sikorski, R., Westerwelle, G., & Martonyi, J. (2013). Letter of the Ministers for Foreign Affairs of Germany, the Netherlands, Finland and Denmark. https://www.cvce.eu/en/obj/letter_from_the_ministers_for_foreign_affairs_of_germ any_the_netherlands_finland_and_denmark_to_the_president_of_the_european_co mmission_6_march_2013-en-832d54b6-e0c2-4896-89b5-47c5a0042e71.html

Schimmelfennig, F., & Sedelmeier, U. (2004). Governance by Conditionality: EU Rule Transfer to the Candidate Countries of Central and Eastern Europe. Journal of European Public Policy, 11(4), 661–679.

Endnotes:

(1) The NGOs were Amnesty International Hungary, the Eötvös Károly Institute, the Hungarian Civil Liberties Union, the Hungarian Helsinki Committee, K-Monitor, and Transparency International Hungary

SAFE but Not Secure: The Challenge of a Common Defence and EU’s Unity

SAFE but Not Secure: The Challenge of a Common Defence and EU’s Unity  Blind Spots in AI Governance: Military AI and the EU’s Regulatory Oversight Gap

Blind Spots in AI Governance: Military AI and the EU’s Regulatory Oversight Gap  One Crisis, Two Views, One Pact: Political Tensions Behind the EU Migration Pact 2024

One Crisis, Two Views, One Pact: Political Tensions Behind the EU Migration Pact 2024  Selective Solidarity: The Desecuritisation of Migration in the EU’s Response to the Ukrainian Refugee Crisis

Selective Solidarity: The Desecuritisation of Migration in the EU’s Response to the Ukrainian Refugee Crisis