Written by: Hannah Staudenherz, Working Group on Migration

Edited by: Nadine Power

Abstract

This paper investigates how different forms of anti-immigration accommodation by centre parties influence the electoral performance of radical-right parties (RRPs) in Europe. While previous research often treats accommodation as a uniform or one-dimensional phenomenon, this study uses both principal component and cluster analysis on data from the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES) (Jolly et al., 2021) and the Manifesto Project (MARPOR) (Lehmann et al., 2024) to identify four distinct accommodation profiles: “Moderate rhetoric, unity, structurally restrictive,” “Anti-Islam, unity, low integration salience,” “Anti-immigration, high dissent,” and “Strongly anti-immigration, assimilationist.” A subsequent regression analysis demonstrates that only the profile marked by explicit cultural-religious framing (“Anti-Islam, unity, low integration salience”) is significantly associated with higher RRP vote shares (+8.4 percentage points). Profiles based primarily on restrictive policy changes or internal division show weaker and statistically insignificant effects. These findings suggest that rhetorical convergence around cultural and religious issues plays a crucial role in legitimising and amplifying radical-right support. Furthermore, they challenge supply-and-demand logics of convergence and instead support issue-ownership theories: when mainstream parties accommodate radical-right narratives, they risk amplifying the salience of these issues.

1. Introduction

Angela Merkel, at the height of Europe’s refugee influx, declared “Wir schaffen das” (“we can do this”), and set a tone of reassurance and solidarity in Germany. Friedrich Merz, however, took the opposite stance ten years later: “In coordination with our European neighbours, we will reject people at our shared borders, including asylum seekers” (Rinke et al., 2025). While such rhetoric might have long been associated with radical-right parties (RRPs), it now illustrates a shift within the immigration discourse among centrist political parties across the European Union.

Indeed, Abou-Chadi & Krause (2020) demonstrate that the emphasis on anti-immigrant and protectionist positions is itself a response to the electoral success of RRPs. In doing so, these parties follow the logic outlined by Meguid (2005), who argues that niche parties become less electorally successful when established parties pursue accommodative strategies. Following this reasoning, RRPs should be less successful when centre parties adopt restrictive immigration positions.

However, empirical evidence has increasingly questioned this strategy’s effectiveness, suggesting instead that adopting radical-right positions can actually strengthen RRPs. According to this perspective, when mainstream parties adopt restrictive immigration stances, they legitimise radical-right positions and boost their salience. At the same time, voters might see RRPs as more authentic on this issue, thus discouraging them from voting for centre parties (Arzheimer & Carter, 2006; Dahlström & Sundell, 2012; Mudde, 2019; Krause et al., 2022).

Given this mixed academic debate, it remains crucial to understand accommodation dynamics in more detail. Recent studies have predominantly treated accommodation as a one-dimensional phenomenon, typically as a simple shift in position. However, the micro-level perspective remains underexplored. One aspect worth investigating further is how centre parties differ in the ways they accommodate anti-immigration positions – not merely along a simple left-right scale but also through distinct rhetorical frames – and whether these strategies affect RRP vote shares differently. Therefore, this paper addresses the following research question: what distinct “profiles” of anti-immigration accommodation exist among centre parties, and how do these different profiles affect the electoral performance of RRPs?

To answer this question, the paper proceeds as follows: first, existing research on anti-immigration accommodation and voter behaviour is reviewed to develop the theoretical framework and clarify the concept of accommodation profiles. Second, the data and methodological approach are explained. The third section presents the empirical findings, followed by a discussion of their broader implications.

2. Literature Review

To fully understand the increased anti-immigration accommodation among centre parties, it is useful to first look closer at the phenomenon of the increased radical-right success in European electoral politics, which has acted as both the starting point and driving factor behind this accommodation (Abou-Chadi & Krause, 2020). Political scientists have extensively studied the reasons behind this phenomenon, primarily focusing on three explanatory frameworks: voter grievances, issue salience and ownership, and voter behaviour related to party competition.

First, the supply-and-demand perspective attributes the success of RRPs to the grievances of voters who feel marginalised or “left behind” by globalisation and societal change. Economic insecurity, rising unemployment, and cultural anxieties related to immigration and multiculturalism create fertile ground for radical-right electoral gains (Norris & Inglehart, 2019; Mudde, 2007; Betz, 1994). RRPs capitalise on voters’ feelings of economic disenfranchisement, cultural threat, and loss of national identity, translating such grievances into electoral support.

Second, scholars point to issue salience and ownership as crucial for understanding the electoral success of RRPs. This perspective argues that new or niche parties can succeed if they effectively claim ownership of salient political issues. In the case of RRPs, it is particularly immigration. When voters perceive these parties as authentic and credible in advocating restrictive immigration policies, RRPs gain electoral traction (Mudde, 2019; Dahlström & Sundell, 2012). Consequently, mainstream parties attempting to mimic RRP positions often fail to persuade voters due to perceived deficiencies in competence and authenticity, thereby reinforcing RRPs’ ownership of these issues rather than diminishing it (Arzheimer & Carter, 2006).

Third, studies focusing on voter behaviour suggest that ideological convergence among mainstream parties contributes to the rise of RRPs. As established parties increasingly move towards the political centre, voter volatility and dissatisfaction grow, pushing voters towards parties that offer clearer, more distinct ideological positions. According to Bartolini and Mair (1990), and more recently Spoon and Klüver (2020), when mainstream parties converge ideologically, electoral volatility increases, benefiting niche or radical-right parties as voters seek alternatives with clearly differentiated policy positions.

Given the sustained electoral success of RRPs, mainstream parties face strategic dilemmas regarding their responses. Meguid (2005, 2008) distinguishes three main strategies: aversion (distancing), dismissal (ignoring), and accommodation (adopting niche party positions). Among these, accommodation, especially in the domain of immigration policy, is frequently chosen by centre parties to address the electoral threat posed by RRPs (Han, 2014; Abou-Chadi & Krause, 2020). This aligns with the initial approach of Meguid (2005), who argues that accommodation would enable the centre party to “steal” both the topic and potential voters from the RRP, aligning with the supply-and-demand arguments.

Yet, recent studies question this assumption and exemplify the difference between Meguid’s theory and its application to reality. Krause et al. (2022) demonstrate that accommodating anti-immigration positions does not systematically diminish radical-right support. In fact, their findings indicate that mainstream parties adopting restrictive immigration stances tend to legitimise the radical-right agenda and further increase its salience, a result that aligns with issue-ownership theories rather than supply-and-demand logic. Their macro-level analysis shows that accommodating rhetoric by mainstream parties has, at best, no significant effect on radical-right vote shares and, at worst, amplifies them. At the micro-level, the data reveal that accommodation often catalyses voter switching from mainstream to radical-right parties, resulting in larger gains for the radical right than losses for mainstream parties. These effects are particularly pronounced where radical-right parties have already established a robust presence and where a cordon sanitaire is enforced by mainstream competitors. Consequently, the research suggests that accommodation by mainstream parties can backfire, inadvertently boosting radical-right support rather than containing it.

Taken together, these studies (Krause et al. 2022; Abou-Chadi & Krause 2020) reveal that for centre parties, accommodation strategies on immigration issues are a high-risk and often counterproductive response to radical-right competition. This suggests that while such strategies may seem logical in a supply-and-demand framework, they may actually backfire by legitimizing radical-right discourses and intensifying issue salience, rather than mitigating the radical right’s electoral appeal.

However, these studies treat accommodation as a rather uniform and one-dimensional phenomenon, focusing only on the fact that far parties move to the right on a left-right scale without considering the different rhetorical frames, policy emphases, or underlying motivations involved. Odmalm and Bale (2014) highlight that immigration policy debates in mainstream parties involve more than just positional shifts. They reveal that parties vary in how they integrate concerns about security, cultural identity, economic impacts, and integration, and these tensions shape not just policy stances but also rhetorical frames.

Thus, despite extensive debate, the question of how exactly mainstream parties accommodate anti-immigration positions and the distinct electoral consequences of different forms of accommodation remain underexplored. The current literature typically treats accommodation as a one-dimensional strategic shift, overlooking nuanced differences in rhetorical framing and policy emphasis. Addressing this gap by investigating distinct profiles of accommodation offers valuable insights into the conditions under which mainstream parties’ accommodation profiles strengthen or mitigate RRP electoral support.

3. Theoretical Framework

This section clarifies how this paper conceptualises “accommodation profiles” as multi-dimensional variations in how centre parties engage with radical-right immigration stances. While previous studies have generally examined accommodation as either rhetorical alignment or policy repositioning, Bale et al. (2009) provide a more nuanced understanding. They argue that centre parties’ responses to radical-right pressures vary not just in whether they shift, but in how extensively, how quickly, and with what mix of talk and action these shifts occur. Their study of four social-democratic parties, Denmark’s Social Democrats, the Dutch PvdA, Norway’s Labour Party, and Austria’s SPÖ, shows that rhetorical signals, actual policy reforms, and the breadth of policy change can follow very different patterns. For instance, the Danish Social Democrats shifted both rhetoric and policy in tandem, moving quickly and comprehensively to adopt restrictive stances in the late 1990s. In contrast, Norway’s Labour Party enacted far-reaching restrictions quietly, without public fanfare or dramatic rhetorical hardening. The Dutch PvdA hardened its language in response to the electoral surge of Pim Fortuyn, but policy reforms lagged behind. Meanwhile, Austria’s SPÖ displayed various signals: periods of restrictive policy-making alternating with rhetorical moderation to appease left-libertarian allies and internal critics.

These examples confirm that rhetoric and policy as part of the accommodation discourse are not uniform. Based on the insights of Bale et al. (2009), three dimensions of accommodation emerge: first, substance, which is the degree to which actual policies change, beyond rhetorical adjustments. Scope defines whether reforms are limited to a single area (e.g., asylum rules) or span multiple policy domains (e.g., citizenship, welfare, labour market access). Third, pace describes the sequence and speed with which rhetoric and policy evolve, either preemptively, reactively, or in a staggered, stop-go pattern. While Bale et al. (2009) do not present these as an explicit typology, their case studies suggest that these dimensions are central to understanding how parties adjust to radical-right pressure. These dimensions map directly onto the theoretical question that this paper poses: when centre parties accommodate radical-right stances on immigration, how do they do so, and in what ways do these approaches differ? Crucially, how might these different forms of accommodation shape the electoral success of RRPs?

Building on the insights of Bale et al. (2009), this paper develops a framework for classifying centre party accommodation along the dimensions of policy substance and scope. In addition, Bale et al. (2009) show how rhetorical signals are deeply intertwined with accommodation, often diverging from actual policy changes. They observe that parties can “talk tough” without acting, “act tough” without loudly advertising it, or do both simultaneously. Thus, their analysis repeatedly shows that rhetorical signals are a central part of party accommodation.

This observation reveals an important gap in the existing literature: while the focus has often been on policy shifts alone, rhetorical framing can independently shape issue salience, radical-right legitimacy, and electoral competition. To address this gap, this paper treats rhetorical framing as an additional, standalone dimension alongside policy substance and scope. By including rhetoric explicitly, the framework captures not only what parties do in terms of policy change but also how they communicate and frame these actions to voters.

However, rather than imposing a fixed typology, this framework aims to provide a heuristic guide for comparing and understanding observed accommodation patterns. The empirical analysis will rely on cluster analysis to identify underlying patterns in the data, ultimately resulting in profiles that can then be analysed with respect to their influence on the radical right’s success. This flexible framework ensures that the classification of accommodation profiles remains empirically grounded while staying sensitive to the multi-dimensional nature of party responses.

Based on the framework outlined and the literature discussed, this paper formulates the following hypotheses to guide the empirical analysis:

- H1 (Salience-Legitimisation Hypothesis): Higher levels of rhetorical hard-line accommodation, independent of substantive reform, are associated with higher subsequent RRP vote shares.

- H2 (Containment Hypothesis): Greater substantive restriction accompanied by low rhetorical salience is associated with lower (or stable) RRP vote shares.

- H3 (Unity Hypothesis): Accommodation profiles exhibiting inconsistent or fragmented cues, either within the party or across the positions, are associated with higher RRP vote shares than profiles showing coherent signals.

In sum, this section has outlined a comprehensive theoretical framework for understanding accommodation as complex, multi-dimensional strategies that centre parties adopt in response to radical-right pressures on immigration. Building on the nuanced work of Bale et al. (2009) and integrating insights from issue-ownership and strategic response theories, this framework distinguishes rhetorical framing, policy substance, and scope as key dimensions along which accommodation varies. By using this framework as a heuristic guide, the subsequent empirical analysis will identify and interpret accommodation profiles and test the hypotheses concerning their distinct impacts on RRP vote shares.

4. Data

To investigate the complex nature of party accommodation strategies in response to radical-right pressures, this study integrates data from two complementary sources: the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES) and the Manifesto Project Database (MARPOR).

The CHES dataset (Jolly et al., 2021) offers expert assessments of parties’ policy substance through analysing immigration policy and multiculturalism (coded as IMMIGRATE_POLICY and MULTICULTURALISM, respectively). Both variables are key indicators of whether parties actually shift their stances on immigration and multiculturalism. To ensure that the analysis only evaluates parties already showing some degree of accommodation, the sample was restricted to those parties whose standardised IMMIGRATE_POLICY score exceeds zero. CHES also includes salience measures (IMMIGRATE_SALIENCE and MULTICULT_SALIENCE), which reflect the prominence parties give to these issues in their public messaging; this is crucial for capturing rhetorical framing and how these issues are prioritised. Importantly for capturing rhetorical framing, CHES also includes the variable ANTI_ISLAM_RHETORIC, indicating the extent to which party leadership engages in explicit anti-Islam discourse, an increasingly salient dimension of radical-right appeals. Finally, measures of internal dissent (IMMIGRATE_DISSENT, MULTICULT_DISSENT) allow this paper to assess internal unity, an important facet of scope in Bale et al.’s (2009) framework.

Meanwhile, the MARPOR dataset (Lehmann et al., 2024) complements this by systematically coding manifesto statements about immigration and integration. The variables PER601_2 (restrictive immigration framing) and PER602_2 (liberal framing) capture the policy substance of how parties position themselves in official platforms. The multiculturalism-related indicators PER607_2 and PER608_2 similarly provide evidence of pro-diversity versus pro-assimilation stances, offering additional leverage for measuring scope, i.e. whether parties’ accommodation extends beyond border control to broader questions of integration and national identity.

By integrating both datasets, this paper can empirically differentiate between rhetorical accommodation (high salience or explicit framing without necessarily enacting restrictive policy), substantive accommodation (actual policy shifts as recorded in manifestos and expert judgements), and the scope of these responses (whether they are broad-based or limited to asylum, for instance).

Furthermore, the focus is on EU countries, consistent with the broader context of radical-right electoral dynamics and mainstream accommodation in Europe and the empirical analyses discussed above (Krause et al. 2022; Abou-Chadi & Krause 2020; Bale et al. 2009). To capture the most relevant period for assessing accommodation profiles, the analysis focuses on the year 2018 as the primary time point because it marks the latest wave of data from the CHES expert survey (Jolly et al., 2021). For the MARPOR dataset (Lehmann et al., 2024), party manifestos from 2018 are used where available. In cases where no 2018 manifesto exists – a total of 36 – the closest available year within a maximum two-year window (2016–2020) is selected. While this approach allows for maximum coverage and comparability, it introduces minor risks of temporal mismatch: party platforms may shift meaningfully even within a few years, especially in volatile electoral contexts. However, limiting the window to four years minimises this risk while avoiding a trade-off in sample size or representativeness. In terms of party selection, the analysis focuses on parties of the political centre: Social Democratic parties, Liberal parties, Christian Democratic parties and Conservative parties. This classification follows standard CHES and MARPOR coding conventions but is cross-checked to avoid misclassification of radical-right parties as centre.

After data cleaning and exclusion of cases with excessive missing information across both CHES and MARPOR variables, the final sample consists of 47 parties across EU countries.

For electoral outcomes, data on vote shares come from the ParlGov dataset (Döring & Manow, 2024). Where ParlGov data was incomplete, national election authorities’ official data were used to fill gaps. A critical point is that not all countries held national elections in 2018 (the focus year of this analysis). In such cases, the first subsequent election is used. While this approach enables cross-national comparability in electoral outcome data, it does introduce potential challenges: for instance, COVID-19 pandemic disruptions in later elections (e.g., 2021) may have introduced additional volatility unrelated to immigration debates and are acknowledged as important limitations.

To account for broader structural and regional factors that may also influence RRP support, data about GDP growth (World Bank Group, 2025a), unemployment rates (Eurostat, 2025), and immigration rates (World Bank Group, 2025b) are included.

5. Methodology

Principal Component Analysis

To empirically identify and evaluate how centre parties accommodate radical-right positions on immigration, this paper employs a three-stage methodological approach: principal component analysis (PCA), cluster analysis, and regression analysis.

The first analytical step is a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) conducted on the above discussed variables representing policy substance (e.g., IMMIGRATE_POLICY), rhetorical framing (e.g., ANTI_ISLAM_RHETORIC), and scope (e.g., PER607_2). All variables are standardised to z-scores to ensure comparability across different measurement scales. The PCA summarises the most relevant variance in the data into a smaller number of orthogonal components. This ensures that following analyses rely on uncorrelated dimensions of variation, which is especially important for overlapping measures of policy restrictiveness, salience, and dissent. Thereby, it reduces the risk of overfitting and ensuring greater model stability (Jolliffe & Cadima, 2016).

Based on the scree plot and eigenvalue decomposition, the first three principal components are retained for further analysis. These components collectively represent the key underlying patterns of how parties combine policy, rhetoric, and dissent when engaging with the immigration issue, aligning with the paper’s theoretical focus on the substance, scope, and rhetorical framing of accommodation. The loadings of the first three principal components were inspected to ensure that they captured meaningful dimensions consistent with the theoretical framework: rhetorical emphasis, policy substance, and internal dissent. This step confirmed that the components represent coherent patterns of variation in party responses.

Cluster Analysis

Using the scores of the first three principal components, a k-means cluster analysis is performed to identify empirically grounded accommodation profiles among the 47 parties. Cluster solutions ranging from k=2 to k=5 are tested using within-cluster sum of squares and silhouette width to determine the most robust and interpretable number of clusters. Although the silhouette measure suggested that a two-cluster solution would offer the tightest internal cohesion, the within-cluster sum of squares yielded a four-cluster solution. The choice of k=4 also better reflects the study’s goal to capture the nuanced, multi-dimensional variation in accommodation profiles that extend beyond a simple binary distinction. The clusters form the foundation for the subsequent analysis of their electoral effects. A detailed description of these accommodation profiles and their distribution across parties and countries is provided in Section 6 (Interpretation).

Regression Analysis

The final analytical step tests how these empirically identified accommodation profiles shape the electoral success of RRPs. Specifically, ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions are estimated with RRP vote share as the dependent variable. The independent variable of interest is the accommodation profile cluster to which each party belongs.

Additionally, the model includes control variables for regional location (region), economic context (GDP_growth, unemployment_rate), and the net migration rate per 1000 inhabitants (immi_per1k). This ensures that any observed relationship between accommodation profiles and radical-right electoral outcomes is not simply a by-product of regional or economic differences. To account for the varying political weight of each party, the regression model also weights observations by party vote share. This ensures that more electorally significant parties exert a proportionally larger influence on the estimated relationships, providing a more realistic reflection of how accommodation strategies shape radical-right support.

The final regression model takes the form:

RRP Vote Share =0+1cluster4+2region+ 3unemployment rate+4immi per1k+5GDP growth +

To ensure the validity of the regression estimates, standard diagnostic plots (including residual vs. fitted plot, Q-Q plot, and leverage plot) were inspected. These checks indicated that the model broadly met the core assumptions of linearity, homoscedasticity, and normality of residuals, with no extreme outliers or influential points unduly distorting the results.

6. Interpretation

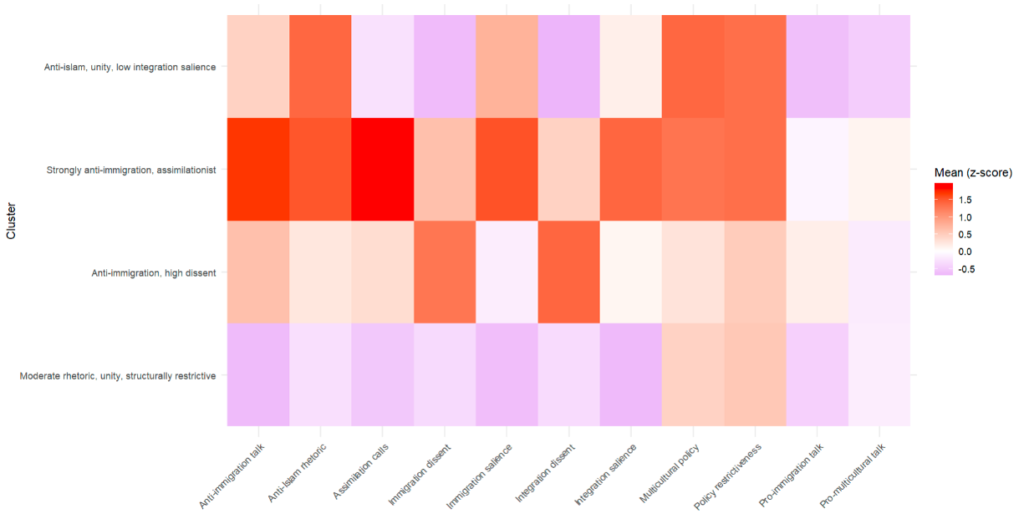

The clustering analysis identified four distinct accommodation profiles among the 47 mainstream centre parties in the EU sample. Figure 1 presents a heatmap showing the average (z-score) values of rhetorical, policy, and dissent variables across clusters.

The resulting profiles are:

- “Anti-Islam, unity, low integration salience”: Comprising 12 parties, this cluster is defined by high levels of anti-Islam rhetoric but relatively low prioritisation of broader integration debates. It indicates an accommodation profile that explicitly engages in cultural and religious framing without giving attention to integration policies.

- “Strongly anti-immigration, assimilationist”: This profile, also containing 12 parties, combines a hardline anti-immigration stance with clear assimilation demands for immigrants and asylum seekers. It also has consistently high scores across rhetorical and policy indicators, showing a coherent, synchronised accommodation profile that mirrors the radical-right’s emphasis on cultural homogeneity and national identity.

- “Anti-immigration, high dissent”: This group of 10 parties is marked by high salience and strong anti-immigration positions but also substantial internal dissent, suggesting that some factions within the party push a restrictive line while others resist or call for moderation.

- “Moderate rhetoric, unity, structurally restrictive”: This cluster consists of 13 parties and is characterised by relatively low salience and rhetorical extremity, combined with moderately restrictive immigration policies and low internal dissent.

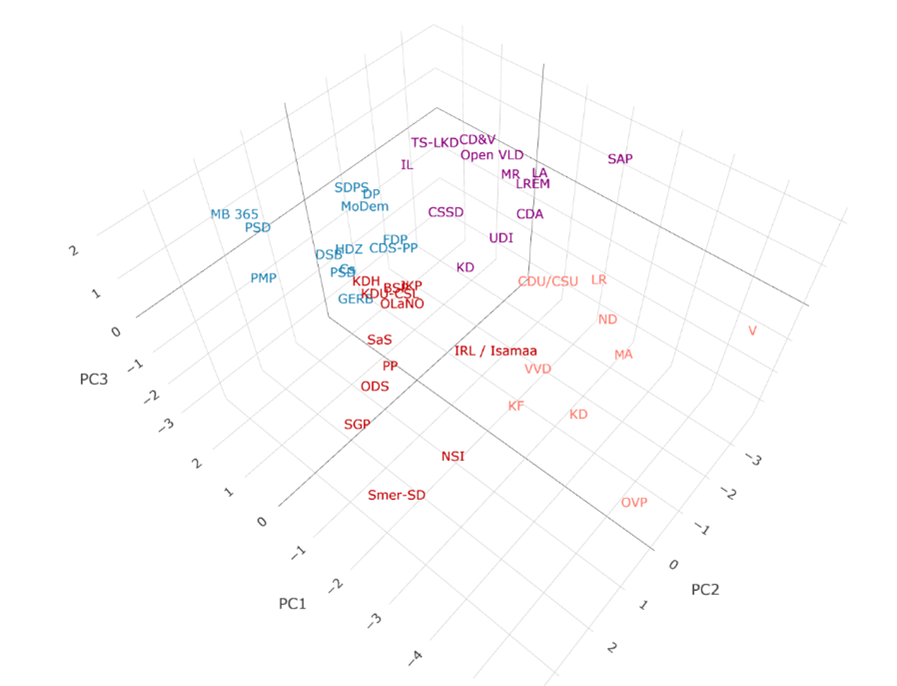

The 3D plot (Figure 2) provides further insights into how these accommodation profiles distribute across countries and party families.

For instance, many centre-right conservative parties cluster in the “Strongly anti-immigration, assimilationist”, while many social-democratic parties fall into the “Moderate rhetoric, unity” group. The “Anti-islam, unity” consists of a high variety of party families, including social democrats as well as liberal and conservative parties. Parties with high internal dissent (Cluster 3) appear more spread out in the principal component space, confirming the less coherent nature of their accommodation strategies.

The nuanced distributions support the theoretical expectation that accommodation is not a linear or uniform process but rather shaped by party-specific ideological traditions, internal factional dynamics, and strategic considerations.

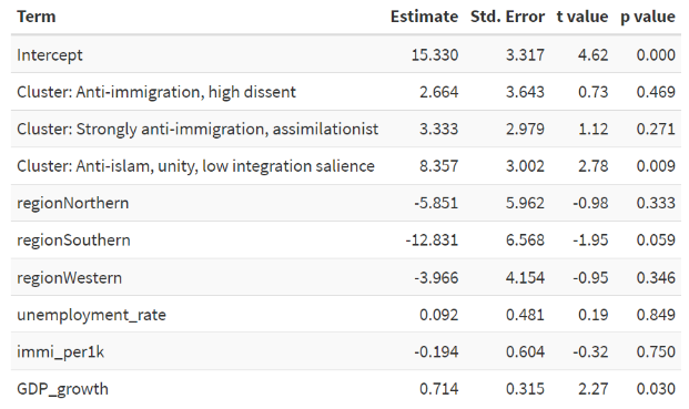

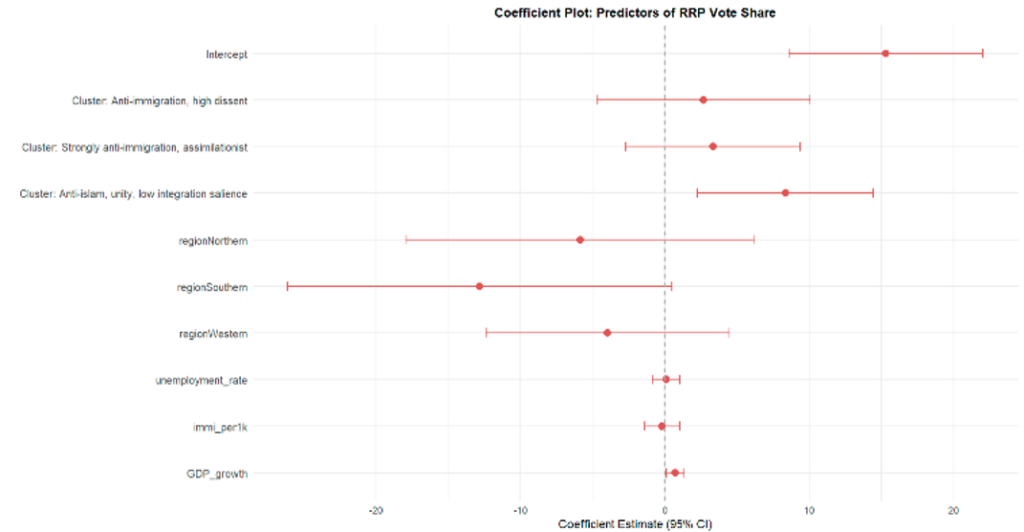

The regression analysis provides further insights into how the accommodation profiles of centre parties shape RRP vote shares. Table 1 and Figure 3 summarise the estimated effects of each accommodation profile, along with regional and economic controls, on RRP electoral success. The overall model explains approximately 51% of the variance in RRP vote share (p<0.001), suggesting that accommodation profiles are a meaningful factor in shaping radical-right outcomes.

The intercept (15.33, p<0.001) represents the expected RRP vote share for parties in the reference group, the “Moderate rhetoric, unity, structurally restrictive” profile, while holding other control variables (region, unemployment, immigration rates, GDP growth) at zero. This positive and significant intercept suggests that for more moderate accommodators, the baseline level of RRP support is around 15 percentage points in the electoral contexts included in the analysis.

A key finding is that the “Anti-Islam, unity, low integration salience” profile is associated with a statistically significant +8.4 percentage point increase in RRP vote share (p=0.008). In practical terms, this profile would be expected to raise RRP support to roughly 23–24%. This highlights how culturally charged rhetorical convergence combined with a neglect of policy initiatives can have a substantial effect on boosting the radical right’s legitimacy and visibility. This finding strongly supports H1: engaging in culturally charged and religiously framed rhetoric, while not providing any policy changes, can lend legitimacy to radical-right narratives and expand their electoral reach.

By contrast, while the other profiles “Anti-immigration, high dissent” (+2.7, p=0.47) and “Strongly anti-immigration, assimilationist” (+3.3, p=0.27) also show positive associations with radical-right vote share, these effects do not reach statistical significance. This suggests that more general anti-immigration positioning or strong policy stances on assimilation, without the specific rhetorical focus on Islam, are less reliably linked to radical-right electoral success. Even though not statistically significant, there is still an indication for support of H3: internal dissent is associated with higher RRP vote shares.

Finally, the results also provide partial support for H2: the “Moderate rhetoric, unity, structurally restrictive” profile (reference category) does not show any significant positive boost in radical-right vote shares, unlike the more rhetorically charged profiles. This suggests that a low-salience, policy-driven accommodation approach does – compared to other accommodation strategies – not fuel radical-right gains.

Among the control variables, only GDP growth emerges as a significant predictor of higher RRP vote shares (p=0.03). This suggests that economic optimism can paradoxically sharpen voters’ focus on cultural and identity issues, heightening the appeal of radical-right narratives. Interestingly, immigration rates as well as unemployment rates or regional factors do not show significant effects in this model, underscoring the importance of accommodation profiles themselves.

7. Discussion and Conclusion

This paper has explored how different forms of centre party accommodation of radical-right immigration positions, captured through data-driven accommodation profiles, shape the electoral performance of RRPs to eventually answer the research question: “What distinct ‘profiles’ of anti-immigration accommodation exist among centre parties, and how do these different profiles affect the electoral performance of RRPs?”. The results revealed four distinct profiles:

- “Moderate rhetoric, unity, structurally restrictive”: a low-salience form of accommodation that does not significantly alter RRP support.

- “Anti-Islam, unity, low integration salience”: marked by explicit cultural-religious rhetoric and associated with a significant +8.4 percentage point increase in RRP vote share.

- “Anti-immigration, high dissent”: a profile with strong anti-immigration signals but internal division, showing positive but not significant associations with RRP support.

- “Strongly anti-immigration, assimilationist”: a hardline stance across rhetoric and policy, which is also positively (though not significantly) associated with RRP support.

These findings suggest that multiple accommodation profiles exist, ranging from moderate to explicit cultural-religious framings. They differ in their effects on RRP performance: while moderate, low-salience profiles appear to stabilise support, culturally charged rhetorical profiles significantly boost radical-right electoral success.

The results underscore that rhetorical convergence, especially when culturally or religiously framed, plays a more decisive role in boosting radical-right success than purely policy-driven accommodation. They also highlight the importance of internal unity: accommodation strategies marked by internal dissent might further bolster radical-right credibility. For parties of the political centre, these findings raise important strategic questions. While accommodation may seem like a promising way to respond to radical-right pressures, the evidence suggests that certain rhetorical approaches can inadvertently legitimise radical-right narratives and boost their electoral support. Even moderate, low-salience forms of accommodation appear to do little to reduce the radical right’s appeal.

Moreover, these results challenge the supply-and-demand logic that simply moving rightward or restricting immigration policy will undercut radical-right support. Instead, they reinforce the perspective of issue salience and ownership theories: when centre parties accommodate radical right agendas, they risk amplifying these issues’ salience and validating the radical right’s claims to authenticity and leadership on immigration.

As already outlined, this analysis relies on a cross-sectional snapshot (around 2018), with some variation in election timings due to data availability. Future research could track how these profiles evolve over multiple electoral cycles. It could also involve the investigation of whether these findings hold in other global contexts beyond Europe.

In sum, this paper demonstrates that accommodation is not a uniform phenomenon: it varies across rhetoric, policy, and scope, with distinct electoral effects. Explicit cultural-religious rhetoric, especially without major policy reforms, can significantly amplify radical-right electoral support, while low-salience accommodations may offer a more restrictive approach. As such, these findings call on centre parties not just to reconsider how they accommodate radical-right narratives, but to question whether accommodation itself serves as an effective strategy to counter radical-right electoral gains.

8. Bibliography

Abou-Chadi, T., & Krause, W. (2020). The causal effect of radical right success on mainstream parties’ policy positions: a regression discontinuity approach. EconStor Open Access Articles and Book Chapters, 829–847. https://ideas.repec.org/a/zbw/espost/198596.html

Arzheimer, K., & Carter, E. (2006). Political opportunity structures and right‐wing extremist party success. European Journal of Political Research, 45(3), 419–443. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2006.00304.x

Bale, T., Green-Pedersen, C., Krouwel, A., Luther, K. R., & Sitter, N. (2009). If you can’t Beat them, Join them? Explaining Social Democratic Responses to the Challenge from the Populist Radical Right in Western Europe. Political Studies, 58(3), 410–426. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2009.00783.x

Bartolini, S., & Mair, P. (1990). Identity, Competition and Electoral availability: The Stabilisation of European Electorates 1885-1985. https://cadmus.eui.eu/handle/1814/7073

Dahlström, C., & Sundell, A. (2012). A losing gamble. How mainstream parties facilitate anti-immigrant party success. Electoral Studies, 31(2), 353–363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2012.03.001

Döring, H., & Manow, P. (2024). ParlGov 2024 Release (Version V1) [Dataset]. Harvard Dataverse. https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/2VZ5ZC

Eurostat. (2025). Unemployment rates by sex, age and citizenship (%) [Dataset]. https://doi.org/10.2908/lfsa_urgan

Han, K. J. (2014). The Impact of Radical Right-Wing Parties on the Positions of Mainstream Parties Regarding Multiculturalism. West European Politics, 38(3), 557–576. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2014.981448

Jolliffe, I. T., & Cadima, J. (2016). Principal component analysis: a review and recent developments. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society a Mathematical Physical and Engineering Sciences, 374(2065), 20150202. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2015.0202

Jolly, S., Bakker, R., Hooghe, L., Marks, G., Polk, J., Rovny, J., Steenbergen, M., & Vachudova, M. A. (2021). Chapel Hill Expert Survey trend file, 1999–2019. Electoral Studies, 75, 102420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2021.102420

Krause, W., Cohen, D., & Abou-Chadi, T. (2022). Does accommodation work? Mainstream party strategies and the success of radical right parties. Political Science Research and Methods, 11(1), 172–179. https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2022.8

Lehmann, P., Franzmann, S., Al-Gaddooa, D., Burst, T., Ivanusch, C., Regel, S., Riethmüller, F., Volkens, A., Weßels, B., & Zehnter, L. (2024). The Manifesto Data Collection. Manifesto Project (MRG/CMP/MARPOR) (Version 2024a) [Dataset]. Berlin: Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung (WZB) / Göttingen: Institut für Demokratieforschung (IfDem). https://doi.org/10.25522/manifesto.mpds.2024a

Meguid, B. M. (2005). Competition between Unequals: The role of mainstream party strategy in niche party success. American Political Science Review, 99(3), 347–359. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0003055405051701

Meguid, B. M. (2008). Party Competition between Unequals: Strategies and Electoral Fortunes in Western Europe. Cambridge University Press. https://assets.cambridge.org/97805218/87656/copyright/9780521887656_copyright_info.pdf

Mudde, C. (2019). The far right today. https://lib.ugent.be/nl/catalog/rug01:002789397

Odmalm, P., & Bale, T. (2014). Immigration into the mainstream: Conflicting ideological streams, strategic reasoning and party competition. Acta Politica, 50(4), 365–378. https://doi.org/10.1057/ap.2014.28

Rinke, A., Eckert, V., & Williams, M. (2025, March 8). Germany’s Merz and SPD clear first hurdle to forming coalition. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/germanys-merz-spd-reach-preliminary-deal-towards-coalition-2025-03-08/

Spoon, J., & Klüver, H. (2020). Responding to far right challengers: does accommodation pay off? Journal of European Public Policy, 27(2), 273–291. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2019.1701530

World Bank Group. (2025a). GDP per capita growth (annual %) [Dataset]. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.KD.ZG

World Bank Group. (2025b). Net migration [Dataset]. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SM.POP.NETM

The ’Ndrangheta’s Infiltration and Threat to European Institutions

The ’Ndrangheta’s Infiltration and Threat to European Institutions  From Paper to Practice: How Grassroots Norms Undermine Gender Rights in Pakistan

From Paper to Practice: How Grassroots Norms Undermine Gender Rights in Pakistan  Exploited Childhoods: The Role of Global Corporations in Perpetuating and Mitigating Child Labour

Exploited Childhoods: The Role of Global Corporations in Perpetuating and Mitigating Child Labour  Human Rights Challenges in Addressing SLAPPs in Media, NGOs and Journalism in the EU

Human Rights Challenges in Addressing SLAPPs in Media, NGOs and Journalism in the EU