Author: Jennifer Shoemaker

Edited by: Kristina Welsch

Following a series of attacks and rise in religious extremism across the European Union in the years of 2015 and 2016, terrorism combatance and crime prevention has continuously been a priority across the member states, with a wide range of new security implementations and deradicalization efforts.

The distinctions of terrorist organizations and causes (ideological, social, religious, amongst others) make it difficult to put forward a single definition. The nature of terrorism is shifting and unstable, and most labelled terrorist organizations reject the label, preferring instead to refer to themselves as combatants or revolutionaries for their causes. France was one of the first countries to legally define terrorism in 1986: “an individual or collective enterprise whose objective is to gravely disrupt public order through intimidation and terror” (Defining Terrorism, n.d.). Terrorism often involves a variety of categorizations, generally being divided between: jihadist/religious extremism, right-wing extremism, left-wing/anarchist, ethno-nationalist/separatist, and others that may fit into other social categories (Terrorism in the EU: Facts and Figures, n.d.). The radicalization process has been used by various researchers and governments, initially proposed by Randy Borum, and can often be generally observed through social and psychological processes such as: pre-radicalization, identification, indoctrination, with the final step of action being when an individual or a group executes the act of violence (What Does Radicalisation Look Like? Four Visualisations of Socialisation Into Violent Extremism, n.d.).

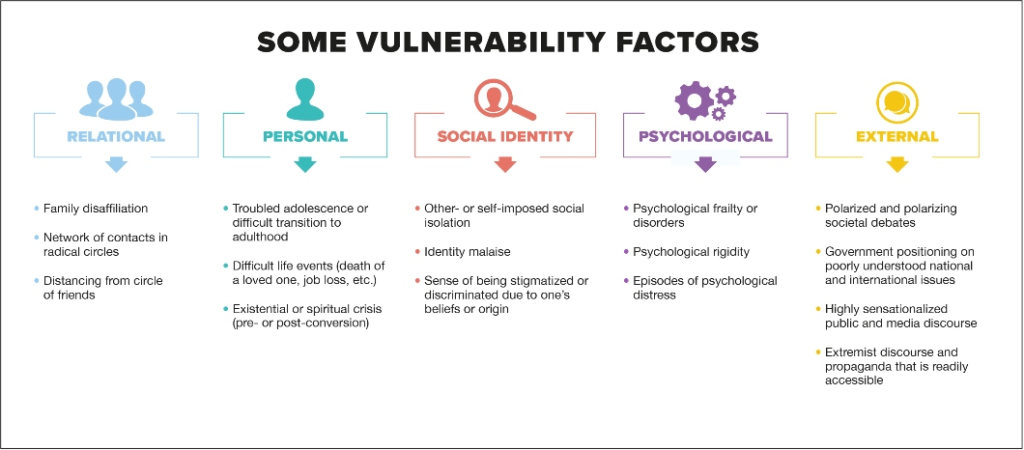

Following 9/11, widespread misinformation contributed to the flawed identification of terrorism on the basis of race, religion, or political markers. Religion is not a direct cause of violence, though it can often be used as a justification. While religion may help some people cope with their difficulties, it is not the primary cause of their radicalizations (Maysun, 2023). Radicalization is non-linear and may involve multiple factors and spaces where an individual begins to reinterpret their religious, moral, and social beliefs. Some individuals are more at risk than others, though anyone could become a target. Risk factors include but are not limited to: struggling with identity and a sense of belonging, mental health issues, a traumatic life event, , family/community views, perceived or actual social deprivation and discrimination, and the feeling of being wronged by either domestic or worldwide events. Some may feel isolated from their community in real life, and attempt to seek community in online spaces (What Does Radicalisation Look Like? Four Visualisations of Socialisation Into Violent Extremism, n.d.).

©Vulnerability Factors for radicalization, summarised by Centre de prévention de la radicalisation menant à la violence (CPRMV),, retrieved from URL https://info-radical.org/en/the-radicalization-process/

The Current Threats: Europol Findings of 2024

- A total of 120 terrorist attacks were carried out in seven Member States in 2024, 98 of them completed, nine failed, and 13 were intercepted. This marks an increase compared to previous years – from 28 attacks in 2022 and 18 in 2021.

- The highest number of terrorist attacks were perpetrated by separatist terrorists (70), followed by left-wing and anarchist actors (32, of which 23 were completed), and 14 jihadist terrorist attacks (of which 5 were completed).

- Out of all the attacks, jihadist terrorist attacks were the most lethal, resulting in six victims killed and twelve injured. 426 individuals were arrested for terrorist offences across 22 EU States and most arrests were for offences related to jihadist terrorism (334).

Economic, social, and political developments across the world influence terrorist and violent extremist narratives and conspiracy theories to circulate, especially through social media and end-to-end encrypted applications (E2EE) (Europol, 2022).

Addressing the Youth

Terrorist and violent extremist groups of all ideologies strategically target young audiences, particularly on social networks. The problem runs deep, as online radicalization includes not only potential violent attackers, but a range of roles including supporters, facilitators, recruiters, propagandists. These groups can still pose a substantial danger to society even if they are not the ones carrying out the violent attacks (Binder & Kenyon, 2022). As seen in multiple investigations, some of those arrested were in contact with each other online and spent time on the same channels and messaging groups where they accessed propaganda, training, and other resources that can be used to plan and carry out an attack. Many radicalized individuals were not sponsored by any particular group, but were within online communities of like minded individuals seeking to take action in real life (Europol, 2022).

Young adults and minors are involved in planning attacks, producing terrorist propaganda, and inciting violence, as younger consumers are often attracted by the aesthetics of today’s propaganda rather than its messages, which is leading to extremist views that lack ideology, but have violence as their common denominator (Europol, 2022). Terrorist and violent extremist groups have adapted their outreach techniques by integrating songs, images and video content. Jihadist networks within the EU remain fragmented, generally lacking hierarchical leadership, and regional or transnational links are often based on the common origin and language of members (Europol, 2022).

The Role of Religious Communities: Potential and Challenges

“Religion is part of the solution, and not part of the problem” said Dr. Douglas Johnson, President of the International Center for Religion and Democracy (ICRD), in a United Nations Commission on Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice session in Vienna in 2016 (DCN21: Defusing Religious Extremism, n.d.). Involving Europe’s religious communities in deradicalization efforts can be crucial for fostering trust, preventing extremism, and rehabilitating individuals influenced by radical ideologies. Religious leaders and communities often hold significant moral authority since religious identity is important for many. It is still a part of daily and cultural life for many people across Europe.

Despite decreasing attendance rates, the importance of identity and the platform religious leaders have can be used to support those struggling and at risk in their communities, both during services and beyond. Religious communities can help people feel a sense of personal security which can positively impact their social identity, and some may not seek community in radical online forums as a result. An analysis of case studies of deradicalization programmes (political and religious) revealed several general and common characteristics of programmes that have demonstrated some levels of success: creating a sense of hope and purpose, building a sense of community, providing individual attention and regimented daily schedules, and sustainable, long-term commitment/care following completion of the programmes (Popp et al., 2020). In a 2017 report by the United States Institute of Peace, conversations that involved religious leaders and the ways they can contribute to deradicalization efforts often brought up issues around training – some religious actors requested physical safety training, noting their high risk and vulnerability when they work to counter violent extremism in their communities. Others stated that they want better training in technology, social media, and communications to help them expand their reach and messaging to their younger religious demographics. In 2020, Imam Hassen Chalghoumi, head of Drancy’s mosque in the Paris suburbs, called on community leaders and parents to speak out against extremism and foster religious tolerance following the extremist attack on Samuel Paty, a school teacher who was beheaded by an Islamic extremist for his class on freedom of expression (Paone, 2020). Though he has been met with threats for some of his views that are deemed ‘moderate’, public voices such as prominent Imams have the capacity to reach many in their communities and work on efforts together with governments and organizations. Some religious actors have expressed interest in expanding their roles as mediators and counselors in their communities through specific skill-based training. Additionally, those religious representatives expressed a need for training in religious literacy across their community but also literacy between policy makers and government officials (Mandaville et al., 2017). Religious literacy should be addressed in various forums, to include community members, local leaders, and government officials, as religious literacy can assist understanding and the capacity to think critically and contextually. In the long term, being skilled in religious literacy and critical analysis could prevent people from becoming vulnerable to radicalization and the misinterpretations of religious texts (Mandaville et al., 2017).

Across Europe there have been attempts and several deradicalization programmes implemented including religious communities, aiming to prevent and reverse radicalization through community engagement, education, and support. In Germany, The Wegweiser Program across North Rhine-Westphalia is an expanding state-run programme that collaborates with local Muslim leaders, schools, and families to prevent youth radicalization. It offers counselling, multilingual social support, events, and religious education to address grievances and counter extremism. The success rates are not published, but programmes and outreach remains active (Aachen, n.d.).

© Programme Guide | City of Aachen https://www.aachen.de/:translation/en/stadt-aachen/de/in-aachen-leben/gesellschaft-soziales-wohnen/integration/programm-wegweiser/

In 2018 in Kosovo, the Ministry of Justice partnered with the Islamic Community of Kosovo to involve Imams in rehabilitating incarcerated individuals convicted of terrorism. The programme included psychological support and religious counselling, aiming to facilitate reintegration into society. The Imams were selected and began lecturing in Kosovo prisons with the aim of deradicalizing prisoners. However, the programme had limited success due to the resistance of prisoners who were sentenced with terrorism offences to take part in the lectures, and an Imam noted that the prisoners did not deem them as legitimate figures who could interpret religious scripture (Orana et al., 2022). In France, the PAIRS (programme d’accompagnement individualisé et de réaffiliation sociale) program was launched in 2018 to support individuals convicted of terrorism-related offenses or those identified as radicalized. The program provides personalized support, psychological counselling, social reintegration assistance, and religious guidance – aiming to prevent reoffending and facilitate reintegration into society. In early 2021, reports indicated that among 64 individuals convicted of terrorism offenses that were enrolled in the PAIRS program, none had reoffended for terrorism-related crimes (Les Résultats Encourageants Du Programme De Déradicalisation Pairs | Ifri, 2021). However, in 2023 a former participant of the program, Armand Rajabpour-Miyandoab, committed a terrorist attack in Paris after a prior 2016 conviction of terrorism (LOEK, 2023).

Conclusion

The inclusion of religious leaders will not immediately solve the problems posed by extremists due to the multitude of factors that lead to radicalization, but their voices of authority and education are valuable and could be necessary – if properly equipped and moderated – in the early preventive/pre-radicalization stages. In particular, they could support people navigating potentially risk-enhancing life situations such as identity struggles, a lacking or diminishing sense of belonging, perceived or actual discrimination, and a family or community. . Religious leaders can provide support on an individual basis, which could step-by-step decrease the amount of people searching for belonging in radical online forums. While certain deradicalization programmes across Europe have shown promising results in preventing recidivism amongst former radicalized people, there are still challenges in deradicalization efforts. Lack of trust in religious authority that is deemed ‘moderate’ by the community may make community members question their legitimacy. This highlights the need for continuous evaluation and adaptation of such programmes to address potential shortcomings, enhance effectiveness, and strengthen religious community involvement through training, allocation of resources, and both religious and media literacy.

References

Binder, J. F., & Kenyon, J. (2022). Terrorism and the internet: How dangerous is online radicalization? Frontiers in Psychology, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.997390

DCN21: Defusing religious extremism. (n.d.). United Nations : Office on Drugs and Crime. https://www.unodc.org/unodc/ngos/dcn21-defusing-religious-extremism.html

Defining terrorism. (n.d.). Musée-Mémorial Du Terrorisme. https://musee-memorial-terrorisme.fr/en/defining-terrorism

European Union Terrorism Situation and Trend report 2022 (TE-SAT) | Europol. (n.d.). Europol. https://www.europol.europa.eu/publication-events/main-reports/european-union-terrorism-situation-and-trend-report-2022-te-sat

Europol. (2024). European Union Terrorism Situation and Trend Report 2024. Publications Office of the European Union. https://doi.org/10.2813/4435152

Les résultats encourageants du programme de déradicalisation Pairs | Ifri. (2021, January 2). https://www.ifri.org/fr/presse-contenus-repris-sur-le-site/les-resultats-encourageants-du-programme-de-deradicalisation

LOEK, A. (2023, December 6). Attaque terroriste à Paris : qu’est-ce que le programme de “déradicalisation” Pairs ? TF1 INFO. https://www.tf1info.fr/societe/attaque-terroriste-a-paris-qu-est-ce-que-le-programme-de-deradicalisation-pairs-suivi-par-l-assaillant-2278286.html?

Mandaville, P., Nozell, M., & United States Institute of Peace. (2017). Engaging religion and religious actors in countering violent extremism. In SPECIAL REPORT (pp. 2–12) [Report]. United States Institute of Peace. https://css.ethz.ch/content/dam/ethz/special-interest/gess/cis/center-for-securities-studies/resources/docs/USIP-Engaging-Religion.pdf

Maysun, J. A. (2023). Are religious beliefs truly the root cause of terrorism? Journal of Global Faultlines, 10(2), 252–263. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48750207

Orana, A., Perteshi, S., & European Foundation for South Asian Studies. (2022). On the Right Path. https://qkss.org/images/uploads/files/Kosovo_report31_03_22.pdf?__cf_chl_tk=7PeuO.rCiJtbanpRJkX6F0sjTBZit_C6bRWtDnZGo7A-1748257922-1.0.1.1-1H9tw4pJbU_4VIGO8z1zYfObVvuVMvCde0bIzAZLcWM

Paone, A. (2020, October 20). French imam says beheaded teacher is martyr for freedom of speech. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/world/french-imam-says-beheaded-teacher-is-martyr-for-freedom-of-spee%20ch-idUSKBN2750AA/

Popp, G., Canna, S., Day, J., & NSI, Inc. (2020). NSI Reachback report [Report]. https://nsiteam.com/social/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/NSI-Reachback_B2_Common-Characteristics-of-Successful-Deradicalization-Programs-of-the-Past_Feb2020_Final.pdf

Terrorism in the EU: facts and figures. (n.d.). Consilium. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/infographics/terrorism-eu-facts-figures/

Terrorism in the EU: trends, terror attacks and arrests in 2023 | Topics | European Parliament. (n.d.). Topics | European Parliament. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/topics/en/article/20250124STO26468/terrorism-in-the-eu-trends-terror-attacks-and-arrests-in-2023

The ’Ndrangheta’s Infiltration and Threat to European Institutions

The ’Ndrangheta’s Infiltration and Threat to European Institutions  From Paper to Practice: How Grassroots Norms Undermine Gender Rights in Pakistan

From Paper to Practice: How Grassroots Norms Undermine Gender Rights in Pakistan  Exploited Childhoods: The Role of Global Corporations in Perpetuating and Mitigating Child Labour

Exploited Childhoods: The Role of Global Corporations in Perpetuating and Mitigating Child Labour  Human Rights Challenges in Addressing SLAPPs in Media, NGOs and Journalism in the EU

Human Rights Challenges in Addressing SLAPPs in Media, NGOs and Journalism in the EU