Written by: Sol Rodriguez, Ambassador for the UK

Edited by: Celina Ferrari

Introduction

During the 2015 Paris Climate Change Conference, countries around the world reaffirmed their commitments to limit the average global temperature increase to 1.5 degrees (C2ES, 2015). At the conference, Carlos Moreno, a professor at Sorbonne University, introduced his “15-minute city” concept as a way to rethink urban spaces and functions intending to tackle greenhouse gas emissions. A “15-minute city” or “city of proximity” is characterised by having self-sufficient neighbourhoods where residents can access all essential services within a 15-minute walk or bike ride. These services must fulfil six social functions: living, working, supplying, caring, learning, and enjoying.

Whereas his urban proposal was introduced in 2015, it was not until the pandemic that Moreno´s innovative concept mesmerised politicians and urban planners. In fact, the concept was popularised after the mayor of Paris, Anne Hidalgo, hired Moreno as a scientific advisor and used the 15-minute concept as part of her re-election campaign (Willsher, 2020). After her victory, Paris has seen an increase in cycling routes, the use of schoolyards or nurseries as recreational public spaces during the weekend, and more pedestrian-only streets (Gongagze et al., 2023). Today, 15-minute cities can be found in Spain (Barcelona), Norway (Oslo), Portugal (Lisbon) or Ireland (Dublin) (Di Marino et al., 2022).

This article argues that to combat climate change, not only must the global economic system become greener, but also the structure of cities. In this regard, the 15-minute city concept might be a key solution to reduce CO2 emissions given the socio-economic and environmental benefits it brings. Even so, it is important to acknowledge the concerns around its potential side effects, especially regarding inclusivity, for Moreno’s idea to be realised.

Context: COVID-19 And The Need To Rethink City Structural Designs

The concept of a 15-minute city garnered attention in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. During lockdowns, citizens faced mobility restrictions and could only leave the house to satisfy their essential needs. This revealed inadequacies in the accessibility of fundamental local amenities in various areas. Consequently, after COVID-19, politicians and urban planners embraced the idea of a decentralised urban model in which shops, parks, and hospitals are moved to where people live, not vice versa.

This idea of decentralisation also served to limit the spread of the virus, as walking and biking were the encouraged methods of transport when public transport was not a feasible option. During the pandemic, with decreased levels of traffic, cities experienced no congestion, as well as reduced noise and air pollution levels. This new scenery received popular support, thus many countries all over the world, especially in Europe, put forward public recommendations in favour of cycling and walking. The city of Milan, for instance, implemented a scheme called “strade aperte” (open streets) to reduce the use of cars (Laker, 2020). Brussels carried out a plan to introduce 40 km of new cycle lanes, later expanded to 50 km (European Cyclists´Federation, 2021). The capital of Spain, Madrid, increased to 36 the number of streets that face car restrictions during the weekend and holidays, allowing pedestrians to walk or exercise (Calleja, 2020).

Green, Healthy And Economically Profitable Cities

The proximity-oriented design of 15-minute cities reduces the time and distance needed to access essential services, which has been reported as having a positive impact on residents. These cities, on the one hand, encourage a healthy lifestyle by prioritising walking or using a bike as the main method of transport. This is extremely important in a context where people are insufficiently active. In fact, the WHO has declared obesity as the new epidemic in Europe, where 59% of adults are overweight or obese, and that number rises to29% for children (William, 2022).

On the other hand, this urban proposal is also beneficial regarding mental health. COVID-19 revealed the existence of another pandemic, a “loneliness pandemic”, in which the feelings of solitude are exponentially increasing among the population. For instance, in 2016, 12% of EU citizens stated feeling frequently lonely, whereas, during the pandemic, this increased to 25% (Baarck et al., 2022). Through the decentralisation of services, the 15-minute city concept could be a way to tackle the feelings of loneliness, given its vision for proximity and social cohesion. Not only does it facilitate access to amenities, services and goods, but Moreno’s idea also increases opportunities for social encounters. For example, he proposes the use of facilities such as schools and hospitals as recreational spaces during the weekend, which in turn increases the supply of spaces available for neighbours to meet. As mentioned in the introduction, this approach is already being implemented in Paris (Gongagze et al., 2023).

Consequently, Moreno’s idea is an alternative to the current urban design where cities and neighbourhoods are specialised in just one activity or function. This creates a sense of segregation between areas of life where citizens live in one part of the city, work in another, and socialise in yet another. In contrast, Moreno´s concept allows for one neighbourhood to fulfil all the activities in the categories of living, working, and enjoying.

The economic and environmental benefits of this urban strategy are also worth mentioning. On the one hand, the delocalisation of urban functions and services can boost local investment thereby increasing opportunities for residents to find jobs that match their skill sets, and consequently, reducing unemployment. For citizens, the 15-minute city model also enables them to reduce transportation costs due to the proximity to essential amenities. Given the closeness of the facilities, private transportation is no longer needed.

On the other hand, the 15-minute city could be a valuable urban tool to tackle climate change. First, it increases car-free walking zones and prioritises cycling and walking routes. Following the logic that all the necessities of daily life are accessible on foot or by a short bike ride, transportation-related emissions will decrease. This has a positive impact in terms of noise and air pollution, which will directly benefit and improve the health of the residents living in the neighbourhood. To illustrate this, the WHO estimated that 7 million people die every year as a result of air pollution (indoor and outdoor pollution) (Roser, 2021). Moreover, the 15-minute city concept usually implies the integration of green spaces into daily life.

Implementation Challenges: Inclusion As A Key Factor For Success

In order for Moreno’s concept to succeed, urban planners need to consider how the 15-minute city concept would affect different collectives, and thus, ensure social inclusivity. To do that, factors such as age, gender and income are extremely relevant.

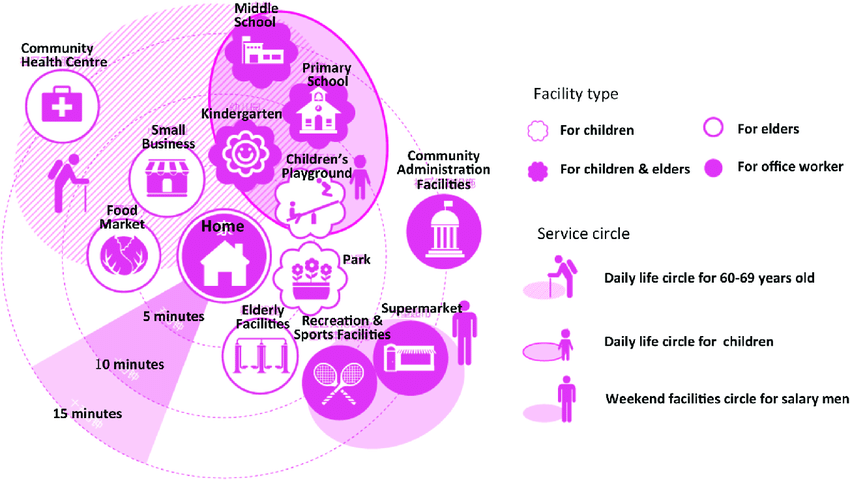

Moreno explains in great detail the benefits having access to all essential services within a short walk could bring to citizens in terms of wellbeing, time and money. However, a challenge that policymakers and urban planners have encountered while trying to bring his concept to life is the fact that people’s travel time and distance are not the same for all social groups. That is, whereas on average the elderly walk at a speed of 3.5 km/h, the numbers increase to 5 km/h when younger demographics are analysed (EIT Urban Mobility, 2022). This gap implies that 15-minute cities need to consider all population groups when measuring the distance between destinations. Moreover, those 15 minutes can be a 15-minute walk or a 15-minute bike ride. Whereas the former would be accessible for the elderly, the latter would constrain their freedom of movement. By not being able to use the bike as a method of transport, certain shops would therefore be out of their reach, which would in turn undermine the 15-minute city´s characteristic of ensuring access to all essential services to residents within a short distance. A potential solution to this challenge can be found in what the cities of Shanghai, Beijing and Guangzhou called “circles”. These consider multiple life experiences, with the distribution of services and facilities within a neighbourhood taking into account the walking distance of children, adults, and the elderly. As the illustration shows, the essential services used by children are all close to each other and similarly for those used by the elderly.

Source: Shanghai Urban Planning and Land Resources Administration Bureau (2016).

This is crucial when designing cities, as many European countries are facing ageing populations. Thus, both policymakers and urban planners need to pay attention to the abilities and needs of the elderly, as well as other population groups with restricted mobility. Similarly, not all citizens know how to ride a bike or want a bike to be their method of transport. Thus, it is argued that the 15-minute concept should accord the same priority to public transportation as it does to biking and walking.

Another factor worth considering is gender. For instance, data show that men cycle more than women. For instance, in Brussels, male cyclists represented 63.8% of the total, while female cyclists accounted for only 36.2%. That same year, 57.2% of bicycle users were male in Barcelona, and only 42.8% were female (GESOP, 2019). The main reason for this gap is safety-related. On the one hand, women may be more reluctant to use the bike due to the inappropriate looks or comments from men, opting for public transportation instead. On the other hand, a lack of proper street lighting or poorly built roads can also discourage people from using this means of transport, especially among beginners, who either have not ridden a bike before or have ridden a bike but not around a city. Consequently, prioritising bike riders should be accompanied by the implementation of safety measures (Stredwick, n.d.)

A third potential problem linked to the 15-minute city concept is the viability of affordable housing, which is connected to concerns regarding social marginalisation and increased inequalities through the creation of ghettos. While Moreno argues that his concept implies ethnic diversity, affordable housing and local jobs, critics have questioned the way in which such goals will be achieved in practice. For example, housing accessibility and affordability in the city of Paris have been in decline for a while as housing costs started to soar during the 2000s. One of the main reasons for this is gentrification and real estate speculation (Guibard and Le Goix, 2024). If the revitalisation of an area leads to rising property values, residents might be forced to move elsewhere (Herbert, 2021).

Similarly, all neighbourhoods should be equally considered for the 15-minute city planning, and one might even argue that poorer suburban areas should have priority over more privileged areas. This prioritisation would avoid further inequalities, as programmes only targeting wealthier neighbourhoods would only lead to more social marginalisation and exacerbate inequalities (Herbert, 2021).

Conclusion

Cities play a pivotal role in sustainable development and are key in the fight against climate change. Carlos Moreno’s “15-minute city” concept has been proposed as an effective alternative to current urban planning design given the environmental, socio-economic and health-related benefits having access to all essential needs within a 15-minute walk or a short bike ride entails. However, this article has pointed out certain concerns, especially in the sphere of social inclusivity, that must be addressed. That is, if the implementation of the concept cannot ensure social inclusivity, then the concept will not be viable in the long term. Consequently, it is essential that 15-minute cities take into consideration the following points: accessibility, safety, and inclusivity to all population groups. This can involve considering different limitations among age groups, how people feel when riding a bike, or whether local investment and revitalisation of areas will hinder current residents.

Being in their infancy, 15-minute cities have yet to provide solutions to certain practical problems or limitations. And thus, that further development is needed to ensure a successful implementation. Consequently, it can be concluded that Moreno’s idea, albeit imperfect, might turn out to be the adaptive solution we need to tackle climate change.

Bibliography

Baarck, J., D´Hombres, B., & Tintori, G. (2022). Loneliness in Europe before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Policy, 126(11),1124–1129. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2022.09.002

European Cyclists´Federation. (2021, March 18) One-Year Anniversary: Will the Pandemic Transform Brussels´Mobility System for Good.

Calleja, I. (2020, May 5). Madrid amplía el tramo peatonal de la Castellana y añade siete nuevas calles para pasear y hacer deporte. ABC. https://www.abc.es/espana/madrid/abci-coronavirus-madrid-amplia-tramo-peatonal-castellana-y-anade-siete-nuevas-calles-para-pasear-y-hacer-deporte-202005131336_noticia.html

Center for Climate and Energy Solutions (C2ES).(2015). Outcomes of the UN Climate Change Conference in Paris. https://www.c2es.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/outcomes-of-the-u-n-climate-change-conference-in-paris.pdf

Di Marino, M., Tomaz, E., Henriques, C. & Hossein Chavoshi, S. (2022).The 15-minute city concept and new working spaces: planning perspective from Oslo and Lisbon. European Planning Studies, 31(3), https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2022.2082837

EIT Urban Mobility. (2022). 15-minute city: human-centred planning in action[Press release November, 16]. https://www.eiturbanmobility.eu/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Press-summary_15min-city_final.pdf

Gabinete de Estudios Sociales y Opinión Pública (GESOP).(2019). Barómetro de la bicicleta en España. https://fevemp.es/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/RCxB-Barometro-de-la-Bicicleta-2019.pdf

Gongadze, S., and Maassen, A (2023, January 25). Paris’ vision for a “15-Minute City” sparks a global movement. World Resources Institute. https://www.wri.org/insights/paris-15-minute-city

Guibard, L., and Le Goix, R (2024) Those who leave: Out-migration and decentralisation of welfare beneficiaries in gentrified Paris. Urban Studies, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/00420980231224640

Herbert, J. (2021, September 2). Transformation or gentrification? the hazy politics of the 15-Minute City. resilience. https://www.resilience.org/stories/2021-09-02/transformation-or-gentrification-the-hazy-politics-of-the-15-minute-city/

Katsis, P., Papergeorgiou, T., and Ntizachristos, L (2014). Modelling the Trip Length Distribution Impact on the CO2. Energy and Power 2014, 4(1A): 57-64DOI: 10.5923/s.ep.201401.05

Laker, L. (2020, April 21). Milan announces ambitious scheme to reduce car use after lockdown. The Guardian https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/21/milan-seeks-to-prevent-post-crisis-return-of-traffic-pollution

Roser, M. (2021, November 25). How many people die from air pollution? [Data set as of November 2021]. OurWorldInData https://ourworldindata.org/data-review-air-pollution-deaths

Shanghai Urban Planning and Land Resource Administration Bureau. (2018). Shanghai Master Plan 2017- 2035. Striving For The Excellent Global City. http://english.shanghai.gov.cn/newshanghai/xxgkfj/2035004.pdf

Stredwick, A. (n.d.) Why don´t more women cycle? We are cycling UK. https://www.cyclinguk.org/article/campaigns-guide/women-cycling

United Nations. (2022, May 3) WHO warns of worsening obesity “epidemic” in Europe. https://news.un.org/en/story/2022/05/1117402

Willsher, K. (2020, February 7). Paris mayor unveils 15-minute city plan in re-election campaign. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/feb/07/paris-mayor-unveils-15-minute-city-plan-in-re-election-campaign

The ’Ndrangheta’s Infiltration and Threat to European Institutions

The ’Ndrangheta’s Infiltration and Threat to European Institutions  From Paper to Practice: How Grassroots Norms Undermine Gender Rights in Pakistan

From Paper to Practice: How Grassroots Norms Undermine Gender Rights in Pakistan  Exploited Childhoods: The Role of Global Corporations in Perpetuating and Mitigating Child Labour

Exploited Childhoods: The Role of Global Corporations in Perpetuating and Mitigating Child Labour  Human Rights Challenges in Addressing SLAPPs in Media, NGOs and Journalism in the EU

Human Rights Challenges in Addressing SLAPPs in Media, NGOs and Journalism in the EU