Written by By Anne Sophie Puers

Abstract

The current Covid-19 pandemic does not only induce a health and economic crisis, but also a crisis of mental health and well-being. Especially young peoples’ mental health is at stake for several reasons, amongst which far-reaching changes to working life. A survey among youth from Italy, one of the countries hit the hardest in the beginning of the pandemic, revealed that hardly any measures exist to promote mental health at work and a vast majority of young people does not know where to find mental health support if needed. It also showed that broaching the issue of mental health at work has a positive impact on individual well-being.

This policy brief therefore offers recommendations to decisionmakers on how to improve mental health and well-being and how to prevent the manifestation of mental health problems in the first place.

Context and scope of the pandemic and its effects on mental health

The Covid-19 pandemic affects people around the world in numerous ways and will have long-term consequences which are not yet all to be foreseen. Whereas youth may be less affected by physical health risks resulting from the Covid-19 pandemic than elder generations, they are overly prone to social, economic and mental health risks.

Above all, young people are disproportionally affected by the consequences the pandemic has on economic factors. During recessions, when the level of unemployment is high, young people are vastly disadvantaged competing with older employees, who tend to be more experienced and better integrated in stable employment relationships.

This already accounted for young people during the previous recession, when youth has been among those groups hit the hardest by the recession following the 2008 economic and financial crisis. It leaves them in a weakened position less resilient to new crises. While youth employment rates recovered over the last years and youth unemployment in the European Union decreased to 14.9% before the onset of the pandemic, youth unemployment rose to 17.6% in August 2020, numbers expected to be rising (Mascherini & Campajola, 2020).

Specifically regarding their employment prospects, young people suffer much more under the pandemic than their elder counterparts, as they amount to an essential part of the economic sectors mostly hit by the pandemic, like the retail, food services, and leisure and hospitality industries (Puerto Gonzalez et al., 2020). Apart from their economic sectors, many more young people are employed based on temporary or low-wage contracts or in more precarious and insecure forms of employment relationship, resulting in higher probabilities to undergo cuts in their working hours or to be dismissed. Besides, structural measures and regulations for employee protections mainly address older employees and impede young employee’s access to the job market (KAWAGUCHI & MURAO, 2014). Especially in Italy, strict regulations, high barriers, labour taxes, and a broad tradition of fixed-term contracts lead to a high level of youth unemployment (Melchiorre & Rocca, 2013).

According to Eurofound (2020), 9.8% of people aged 18-34 became unemployed due to the Covid-19 pandemic and 16% of young Europeans were afraid to lose their job within the next three months.

Even people who are not affected by job loss currently experience fundamental changes which the world of work undergoes owing to the Covid-19 pandemic. These include a generally higher job insecurity, teleworking, reduced working hours, changes of occupation, more exhausting working conditions, more difficult transition from education to employment, and many other factors (Dominguez, 2020).

These conditions, together with the social isolation during lockdowns, do not only affect young people’s long-term employability, but also have a heavy impact on mental health and well-being.

Whereas young people normally score highest on mental well-being compared to other age-groups, this trend has been reversed following the Covid-19 pandemic, Eurofound researchers Mascherini and Sándor (2020) found. In July 2020, 48% of young Europeans were at risk of depression and 20% felt tense ‘all or most of the time’, indicating risk of anxiety (Mascherini & Campajola, 2020). Meanwhile, 17% expressed suffering from loneliness. As numbers have been even higher in April 2020 (55% at risk of depression, 20% feeling lonely, 22% feeling tensed), an increase is also likely to be observed for the present lockdown and the next months to come. Young people now also report lower life satisfaction than people aged 50+, in contrast to surveys from before the pandemic, where young people normally showed a higher life satisfaction.

Italy: a closer look

One of the countries first hit by Covid-19 and still most affected by the pandemic and its consequences is Italy. Especially the northern Italian regions were confronted with a high number of cases and severe restrictions. Following quarantines of whole municipalities in Northern Italy by the end of February 2020, in the beginning of March 2020 all schools and universities in Italy had to close, and a few days later, nearly all commercial activity except food supply was stopped by the Italian government. Although the curve flattened due to these measures and restrictions were eased during summer, universities remained closed for on campus teaching and had to shift to online lessons. Among others, the pandemic has caused severe consequences for the country’s economy and employment.According to Eurofound, 7% of Italians have become unemployed since the beginning of the pandemic, 45% report a decrease in working hours, signifying the highest decrease in working hours (-9.7%) in Europe, and 44% indicated they were exclusively working from home.

In October 2020, the Italian government again ordered restrictions to contain the number of cases, but in November 2020, Italy still was among the countries reporting the most active cases of Covid-19 worldwide, and the Italian ministry of health estimated that since the onset of the pandemic, about 1.5 million Italians have been infected (Ministero della Salute, 2020a).

Besides, Italy has already been among the European countries most affected by youth unemployment (44.1%) during the last economic crisis (European Parliament, 2020) and thus is in a specially delicate position when it comes to the economic consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic.

The current research

In order to take effective measures against the occurring mental health crisis following the Covid-19 pandemic, an overview over the current situation, the trends, and numbers is needed. This policy brief hence aims to look at different aspects of mental health, well-being, and youth employment among Italy’s young employees. It takes a look at the working conditions during the pandemic, assesses the general consciousness about mental health issues, and compares well-being before and during the pandemic. Moreover, the accessibility of mental health support at work (and beyond) provided to young people before and after the pandemic is evaluated, as well as the state of information about mental health support at work and the willingness to draw on these offers.

In order to face these puzzles, an online survey designed for this study and including the WHO-5 well-being index has been conducted among 118 young Italians between the age of 18 and 34 in November 2020.

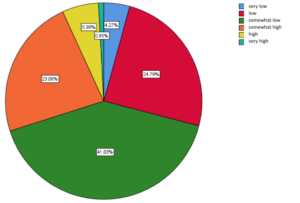

The survey revealed that 37% of the respondents had lost their job, 17% had to shift their work to home office, and 8% had to reduce working hours or changed their job due to the pandemic. Out of all participants, only 7% report a high or very high level of well-being, whereas 29% report a low or very low level of well-being. Figure 1 illustrates the responses given by all participants in the WHO-5 questionnaire.

Figure 1

Overall Level of Well-Being Assessed by the WHO-5 Questionnaire.

Apart from the WHO-5 well-being index, well-being was assessed through the following four dimensions: sense of isolation, stress, anxiety, and depression. Of all participants, 29% of the respondents reported that they felt more anxious after the start of restriction measures and 40% even much more anxious, 68% felt more or much more depressed, and 80% felt both more or much more isolated and more or much more stressed than before the pandemic. In general, 84.5% reported their well-being was significantly lower than before the pandemic, while less than 1% indicated it was not at all.

15% of the respondents received individual psychological support during the pandemic, half of them did not get professional support before.

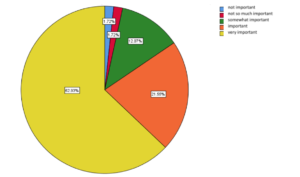

More than 80% of all subjects consider psychological support at work important or very important (63% very important, 22% important). No respondent considered psychological support as not important at all. Figure 2 illustrates the frequency distribution of given responses.

Figure 2

Percentages of Respondents Considering Mental Health Support at Work Important.

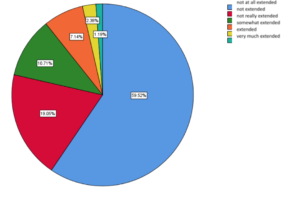

On the other hand, only 14% indicate that mental health support has been effective before the pandemic, while 22% indicate it has not been at all. These numbers even decreased during the pandemic. Now only 7% consider mental health support to be effective, half of the number of participants which indicated it had been effective before. Only 3% report that during the pandemic employers have extended existing measures of mental health support, and 11% report that new measures have been taken against mental health problems at work during the pandemic. Yet, 79% report that employers did not extend existing measures of mental health support, and 18% report they only marginally did. Figure 3 illustrates the number of measures extended during the pandemic. Concerning new measures, 50% report that no new measures were taken at all, and 39% report that hardly any new measures were taken.

Figure 3

Percentages of Respondents whose Employers Have Extended Mental Health Support During the Pandemic.

Only 8% indicate their employer offers psychological support at all, and even less employers inform about where to find support (2%). The same accounts for the regional governments.

In only 5% of all cases, mental health has been a topic at work before the pandemic and only 15% feel comfortable discussing mental health topics in general at work. When it comes to personal mental health issues, only 3% indicate they would talk about them to their employer.

In general, only 7% consider themselves well informed about psychological support at work, while 33% indicate they are not informed at all, and two thirds of the respondents indicate they would not know where to find psychological support if needed.

The amount of psychological support offered turned out to significantly predict the individual well-being, and so does the extent to which mental health is discussed at work. The use of social media seemed to have a positive influence on well-being, too. The extent of discussion, as well as the state of information about mental health support – that is, the overall presence of the topic – , has positive effects on the openness to ask for psychological support, if needed.

The amount of information about psychological support offered by regional governments turned out to be positively related not only to the respondents’ knowledge about where to find psychological support (Pearson’s r = .38, p < .001), but also to the number of measures offered to improve mental health: the more governments informed about mental health support, the more measures were offered by employers (r = .55, p < .001) and the more contented respondents were with the support offered during the pandemic (r = .53, p < .001). Whether mental health had been discussed at work before also turned out to be positively related to the support offered during the pandemic (r = .64, p < .001).

Policy responses

To quickly react to the impact the Covid-19 pandemic has on national economies, the European Union has established the new instrument for temporary Support to mitigate Unemployment Risks in an Emergency (SURE). It serves to support and protect people in jobs affected by the pandemic. As one of the countries mostly affected by the pandemic, Italy has received €10 billion, and under completion of the SURE disbursement, will have received €27.4 billion in the form of loans granted on favourable terms (European Commission, 2020c). This financial support is meant to be used to cover increases in public spending to preserve employment, finance short-time work schemes and support self-employed. It can also be used to finance health measures in the workplace and thus contribute to the recovery of normal economic activity.

In October 2020, all European Union Member States also agreed on a reinforced youth guarantee, a programme which is now addressed to all young people from 15 to 29 years of age, designed to ensure their integration in the labour market or educational system by individualised job support, guidance, and crash courses (European Commission, 2020a). In Italy, the programme is coordinated by the National Agency for Active Labour Policies (ANPAL) and has already been drawn on by more than 1.5 million young people not in employment, education, or training (European Commission, 2020b).

Since February 2020, the Italian government has approved several decrees to introduce financial support to enterprises and self-employed imperilled by the pandemic (e.g., Presidenza del consiglio dei ministri, 2020; Presidenza del consiglio dei ministri, 2021). They do however not directly aim to support youth employment. In addition, in February 2020 the Italian Health Ministry published a briefing note compiling strategic guidelines on how to manage mental health and the psychosocial aspects of Covid-19 (Ministero della Salute, 2020b). And in May 2020, the Italian National Institute of Health (ISS) presented an intervention programme to maintain mental health during Covid-19, based on strategic recommendations of the World Health Organization (Veltro et al., 2020). The programme integrates networks of psychosocial support, consisting of experts and voluntary associations.

Policy recommendations

Whereas both the Italian government and the European Union have reacted to urgent economic needs resulting from the Covid-19 pandemic, concrete measures to maintain mental health of the workforce have hardly been taken yet. One may argue that in the current crisis among all challenges mental health is not a priority, but still the mental health emergency caused by the pandemic should not be forgotten.

Mental health should particularly be included in the measures taken to support national economies. As individuals are investing a vast share of their every-day life at work, quality jobs and well-being at work are an essential aspect of a person’s quality of life and general well-being. The severe changes of working life due to the Covid-19 pandemic therefore directly affect individual well-being.

In return, a (mentally) healthy population implies a healthy economy, as mental health problems cause significant deficits and burdens to the economy, as well as the social and educational systems. Taking measures now to promote mental health is therefore not only important for individual well-being, but also has a positive impact on national economies in the long term.

Besides the economic aspect, the Covid-19 pandemic threatens young peoples’ mental health in several ways:

First, making up a big part of the workforce in retail and food service industries, many young people are continuously risking their own health through customer contact, a factor which is not to be underestimated regarding its impact on psychological stress and well-being in general.

Furthermore, the lack of social interaction due to the pandemic especially hit young people, who are predominantly used to more participation in public and social life under normal conditions than older age-groups. As the current research indicates, the strict limitation of social contacts and the reduction of public life and events has exceptionally critical consequences on their mental health and well-being.

Third, the use of social media in this context turns out to be a double-edged sword. Because although the use of social media as the central matter of social interaction during the pandemic proved to have a positive impact on well-being, it can also pose a threat. This is, because by shifting not only a major part of social interaction, but also of working and educational life, to online communication, boundaries get blurred, and the work-life-balance is disturbed. Here again, young people are especially prone to the negative consequences, as for most young people, it is disproportionally difficult to (mentally) disconnect. With these new modes of work and education, a promotion of the right to disconnect therefore is urgently needed.

As survey results showed, providing information and discussing about mental health is vital for both young peoples’ openness to ask for help if necessary and their general well-being. Far too less support is yet offered and with 37% of all respondents, an alarmingly high number of young people would not know where to find help in case needed.

Structural measures to support employees suffering from mental health conditions and measures to inform about mental health problems, together with prevention in the first place, therefore play an important role in defeating the negative impact of the Covid-19 crisis on our society. To broadly prevent mental health issues, both policymakers and employers must better inform about both mental health issues and offers of support. They must develop strategies to make mental health support broadly accessible, to improve the mental health conditions of affected employees and – first and foremost – broaden the floor for public discussion, to raise awareness about mental health issues in general and inform about providers of support.

References

Dominguez, T. (2020, November 16). The hidden health crisis: the dramatic impact of COVID-19 on young people’s mental health. EURACTIV.Com. https://www.euractiv.com/section/politics/opinion/the-hidden-health-crisis-the-dramatic-impact-of-covid-19-on-young-peoples-mental-health/

Eurofound (2020). Living, working and COVID-19.

European Commission. (2020a). The reinforced Youth Guarantee. https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=1079

European Commission. (October 2020b). Youth Guarantee country by country:: Italy.

European Commission. (2020c, October 27). €17 billion under SURE to Italy, Spain and Poland [Press release]. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_20_1990

European Parliament. (2020). Youth employment: The EU measures to make it work. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/headlines/priorities/social/20171201STO89305/youth-employment-the-eu-measures-to-make-it-work

KAWAGUCHI, D., & MURAO, T. (2014). Labor-Market Institutions and Long-Term Effects of Youth Unemployment. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 46(S2), 95–116. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmcb.12153

Mascherini, M., & Campajola, M. (2020). Youth in a time of COVID. https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/publications/blog/youth-in-a-time-of-covid

Mascherini, M., & Sándor, E. (2020). Is history repeating itself? The impact of the COVID-19 crisis on youth. https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/publications/blog/is-history-repeating-itself-the-impact-of-the-covid-19-crisis-on-youth

Melchiorre, M., & Rocca, E. (2013). The Unintended Consequences of Italy’s Labour Laws: How Extensive Labour Regulation Distorts the Italian Economy. Economic Affairs, 33(2), 156–173. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecaf.12012

Ministero della Salute. (2020a). Nuovo coronavirus. http://www.salute.gov.it/portale/nuovocoronavirus/homeNuovoCoronavirus.jsp

Ministero della Salute. (02/2020b). Affrontare la salute mentale e gli aspetti psicosociali dell’epidemia di COVID-19 [Press release].

Presidenza del consiglio dei ministri. (2020). DECRETO-LEGGE 14 agosto 2020, n. 104 – Normattiva. https://www.normattiva.it/uri-res/N2Ls?urn:nir:stato:decreto.legge:2020-08-14;104!vig=

Presidenza del consiglio dei ministri. (2021). DECRETO-LEGGE 22 marzo 2021, n. 41 – Normattiva. https://www.normattiva.it/uri-res/N2Ls?urn:nir:stato:decreto.legge:2021-03-22;41

Puerto Gonzalez, S., Gardiner, D., Bausch, J., Danish, M., Moitra, E., & Yan, L. X. (2020). Youth and COVID-19: impacts on jobs, education, rights and mental well-being: survey report 2020. ILO. https://www.voced.edu.au/content/ngv:87705

Veltro, F., Calamandrei, G., Picardi, A., Di Giannantonio, M., & Gigantesco, A. (05/2020). Indicazioni di un programma di intervento dei Dipartimenti di Salute Mentale per la gestione dell’impatto da epidemia COVID-19 sulla salute mentale.

Unity and Disunity in EU Diplomacy: Why Speaking with One Voice Remains Difficult

Unity and Disunity in EU Diplomacy: Why Speaking with One Voice Remains Difficult  Sharing the Costs of Climate Ambition: Rethinking Justice in the EU’s CBAM

Sharing the Costs of Climate Ambition: Rethinking Justice in the EU’s CBAM  The ’Ndrangheta’s Infiltration and Threat to European Institutions

The ’Ndrangheta’s Infiltration and Threat to European Institutions  From Paper to Practice: How Grassroots Norms Undermine Gender Rights in Pakistan

From Paper to Practice: How Grassroots Norms Undermine Gender Rights in Pakistan