Written by Marleen Ensink and Juan Antonio Moreno Jurado, Working Group on Migration

Abstract

This report aims to show an accurate picture of the migration context in Europe, more specifically on the management of (in)formal refugee camps, taking the case of the Calais refugee camp as an example. The first paragraph provides a general overview and several insights into the European migration context. The following three chapters dive deeper into the explanation of the differences between refugee camps and self-settlements, as well as the actors involved in the control and management of these spaces and the differentiation between unaccompanied, separated and refugee children. Finally, through the case of the refugee camp in Calais, readers will be able to gain a clearer idea of this sensitive issue that must receive more attention.

Keywords: Refugees, (in)formal settlement, camp management, unaccompanied children, Calais

A brief explanation of the European migration context

The hope of finding a new opportunity on the European continent turns out to be a nightmare for many migrants and refugees. The absence of the European Union (EU) in implementing migration policies and the lack of agreement among Member States (MbS) to manage migration flows do not seem to be having a positive impact. The consequences of these dubious strategies and measures developed by the MbS and the EU can be seen in the management of (in)formal refugee camps in Europe and in ensuring adequate protection for minors.

The worrying management of migration flows became more palpable with the advent of the so-called migration crisis of 2015. On top of that, the unprecedented number of new challenges brought by the Covid-19 pandemic raised further questions about the common tools used by the EU and its MbS to address this phenomenon. Moreover, the current context of the EU is leading to an increase of border restrictions, and thus, a partial halt to human movement between countries; for instance, around 6,200 children arrived in Europe between January and June 2020, 32% less than the first half of 2019 (8,236) (UNHCR, UNICEF, IOM 2020).

In a report published by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), and the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) stated that: ‘Out of the total number of children who sought international protection in Europe between January and June 2020, around 80% of them were mainly registered in Germany (37%), France (14%), Greece and Spain (12% each) and the United Kingdom (UK) (5%)’. However, countries such as France and the UK, face major legal and humanitarian dilemmas. The double-bind policies of both states in their responses to the plight of minors in the so-called ‘Jungle’ or Calais refugee camp (“a makeshift camp”) (Ibrahim 2020, p2), and the absence of the EU’s involvement, call into question the effectiveness of their policy decisions in managing the Calais context. Furthermore, the official implementation of the Brexit deal and the UK’s official exit from the EU has created more uncertainty about the future of the ‘Calais child’ (Idem.), who is trapped in the border policy game between France and the UK while being subjected to the violence of sovereign states.

Refugee camps or self-settlement

The international refugee regime is based on the need for protection. Human rights are at the core of this approach, which means that asylum seekers are granted economic and social rights and that the principle of non-refoulement is ensured (Bakewell 2014, p118). The main method of refugee assistance in this rights-based approach is taking in refugees and placing them in refugee camps or planned settlements (Stevens 2016, p266). Therefore, according to Bakewell (2014), encampment refers to ‘a policy which requires refugees to live in a designated area set aside from the rest of the country and, which is for the exclusive use of refugees, unless they have gained specific permission to live elsewhere (Bakewell 2014, p118). Basic services of water and sanitation are provided, and education might be available when the camp is used for a longer period of time.

In addition to Bakewell, Schmidt (2003) argues that camps are often characterized as a place where refugees are being segregated from the rest of the host society. The campsites have limited access for outsiders and are controlled, which restricts the mobility of refugees, which in turn leads to refugees’ dependence on relief organisations (Bakewell 2014, p118).

To better understand, and in an attempt to characterize refugee camps, Jacobsen (2001) created a typology based on five parameters: (i) freedom of movement, (ii) mode of assistance, (iii) mode of governance, (iv) designation of temporary locations and (v) population size or density. She imagines camps as temporary places that are frequently overcrowded and where the freedom of refugees is restricted. The level of control in camps is high and socio-economic, political, and cultural freedoms are particularly controlled (Idem.). This conception of the camp is in accordance with what Schmidt discusses in her report (2003). Jacobsen adds that the mode of assistance can differentiate between camps where refugees are dependent on economic assistance and camps that allow for a higher engagement of refugees in local economic activities (Idem.). For instance, during the ‘70s and ‘80s in Tanzania, Zambia, Sudan, and Uganda, the agricultural settlement was popular; each refugee household was allocated a plot of land that they were allowed to cultivate, thereby making a living for themselves. The engagement of refugees in the local economy in this instance was much higher than in the traditional refugee camps that we see more often nowadays.

Besides residing in refugee camps, another option is available for refugees that seek asylum, namely self-settlement. Self-settlement does not necessarily mean illegal settlement, however in most countries where refugees do self-settle outside formal refugee camps, they are in breach of the law, and they fall outside the formal governmental system (Bakewell 2014, p120). The people who choose to self-settle are invisible to the UNHCR and are thus not subjected to any formal refugee protection. The choice for self-settlement is regularly made based on a trade-off between aid that is supplied in camps and the opportunity to maintain autonomy, independence and make a better life for themselves. Further, reasons for refugees to choose for self-settlement over formal refugee camps could be based on prior experiences in camps where they have been deprived of their privacy and were restricted in their movement and economic activities, which fuels a fear of losing power and control over their lives. Another driver, which drives self-settlement, is a fear of forced repatriation and the reputation of camps for disease, death, or a generalized fear to adapt to the lifestyle of the camp (Idem.).

But, the line between refugee camps and self-settlement is not always as clear as proposed by these authors. In the example of the agricultural camps in Tanzania, Zambia, Sudan and Uganda, the line between camp and host country blurs. Refugees are given plots of land and their lives intertwine with the lives of locals. Diana Martin, in her study of Palestinian refugees in Beirut, proposes the idea of the ‘campscape’ (2005). She argues that the perception of camps as states of exception placed outside the judicial order, and without contact with the host country, is not always applicable. In her concept of ‘campscape’, the lines between different forms of settlements and the host country are blurred. With this concept, she tries to describe a more fluid spatialization of the sites, which often also includes citizens from the host country (Martin 2015, p14). This is in accordance with the example of the agricultural camps.

Camp management and aid for refugees

Under the rights-based international refugee protection regime, refugees are entitled to basic human rights. The UNHCR is the main actor who supports local governments in refugee protection practices and holds them accountable for keeping their borders open for asylum seekers. In turn, (local) NGOs oversee the UNHCR for honouring the human rights of refugees. As mentioned above, the idea of the refugee camp stems from this internationally established refugee regime and it is the main practice in refugee protection. To account for refugees’ human rights while residing in refugee camps, the UNHCR created an emergency handbook on camp coordination and camp management. This UNHCR camp coordination and camp management (CCCM) handbook is a collection of standardised coordination mechanisms that apply through the refugee coordination model. These mechanisms ensure that basic services are delivered, and protection is guaranteed, whether you live in planned camps, reception, or transit centres, or even in self-settled informal sites (UNHCR 2021).

The UNHCR separates camp coordination and camp management into three distinctive responsibilities that apply to three different actors. The first responsibility is camp administration and this is carried out by the host state, which should provide protection and assistance to refugees and displaced people that land on their territories. This includes supervision of all camp activities, like the security of and security in the camp (Idem.)

The second responsibility is camp coordination, which refers to the role of creating a necessary space for refugees and displaced people. Through the planning and through the establishment of the campsite, information management and through setting standards for the camp. Where camp administration is administered at the state-level, the camp coordination is functioning at the inter-camp level and is carried out by UNHCR. An important part of camp coordination is the development of exit strategies and durable solutions. This part of the responsibility is often shared with civil society and local actors (Idem.).

The third responsibility is camp management. This entails the coordination and monitoring of the delivered services. The actor is responsible for these checks the level of access to services, the level of protection and is responsible for the maintenance of the infrastructure of the camp. The main actors responsible for camp management are NGOs, national and local authorities. If the capacity of these actors is limited, the UNHCR might support camp management (Idem.).

This handbook created by the UNHCR on camp coordination and management gives an important role to local and regional NGOs. NGOs take the role of distributor of food, clothing, blankets, and other necessary items. Besides, they are the ones that provide services within the camp; for instance, basic care services, education, wells, and latrines digging. NGOs are also often the ones with extensive field experience and knowledge of local contexts. They play an essential role in educating others on the early signs of crisis. They expose human rights violations and upsurges in ethnic violence that might lead to an increase in migration. This means the role of NGOs extends way beyond field assistance; in as much, they also provide information, educate others, lobby for refugee rights, provide help to secure refugees’ right to asylum, and help integration in new countries. NGOs are frequently funded by governments, and in opposition to the UNHCR, they exercise a certain level of independence (Berthiaume 1994).

A brief analysis of the concepts of unaccompanied, separated, and refugee minors

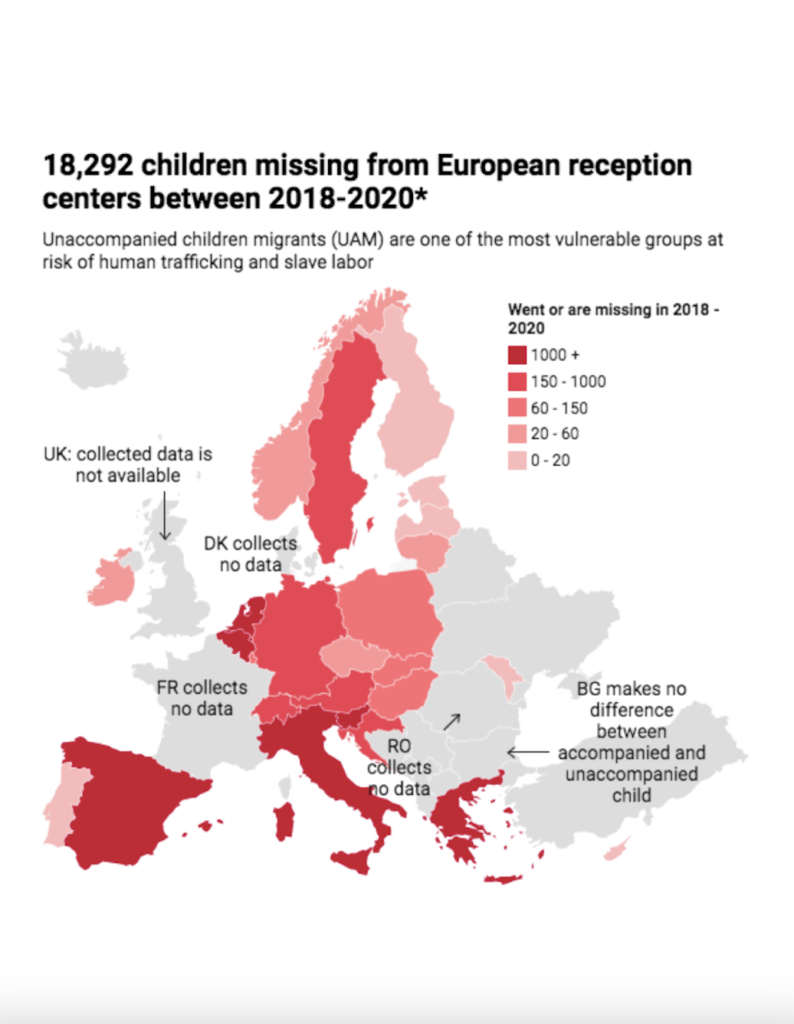

Although this comprehensive UNHCR handbook offers a holistic view of camp management, in practice, the application of these methods is much more complex. One example of the many challenges that can be encountered is the management of unaccompanied minors living in these camps. One of the latest reports published by Lost in Europe, a cross-border journalism project, revealed that around 18,292 children have gone missing in Europe between 2018-2020 (Stroobant 2021).

On the one hand, we have the differences between unaccompanied and separated minors, and on the other hand, refugee minors. According to the UNHCR, UNICEF, and IOM, the main differences between unaccompanied and separated children are that; the former is a ‘child separated from both parents and other relatives, and they do not receive care from any other adult who, by law or custom, is responsible for doing so’ (International Committee of the Red Cross, 2004); while the latter, the ‘child has been separated from both parents and previous customary or legally responsible, but not necessarily from other relatives’ (UNCHR, UNICEF & IOM 2018, p8). Hence, unaccompanied children are alone without any support, while separated children can be accompanied by other adult family members.

Then, regarding refugee minors, according to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), they are classified as ‘rights-bearers’, but in practice, contemporary states do not develop uniform policies and practices. Hence, despite the fact that the 1989 Convention on the Rights of the Child imposes more obligations on signatories to protect children, the definition of a ‘refugee child’ and the interpretations of ‘refugee children rights’ are implemented differently in international and national legal frameworks (Lawrence, Dodds, Kaplan & Tucci 2019). According to the Convention on the Rights of the Child, the term child refers to ‘every human being below the age of eighteen years old unless, under the law applicable to the child, the majority is attained earlier until they are eighteen’. Another aim of this Convention was to achieve a change in the treatment of children, thus, considering them as decision-makers who do not only belong to their parents, but who also have their own rights, and separating childhood from adulthood (UNICEF, 2021).

Once these unaccompanied, separated or refugee minors have arrived at any EU Member State, one of the main legal routes for a safe passage is under the Dublin Regulations III. The Dublin system, which entered into force in July 2013, established the mechanism and criteria for determining the MbS responsible for studying this country’s national or stateless person’s applications for international protection and to be lodged in one of the “Dublin Countries”.

However, the responsibility of the asylum request by a third-country national or by a stateless person must be applied by the first country where the person arrives or where local authorities identify them (Ammairati, 2015). Hence, despite the fact that one of the main aims of the Dublin regulations was to facilitate family reunion (Ibrahim, 2020: 3, 4), and therefore, to relocate unaccompanied children to a country where they have relatives or close family, their will is usually not considered.

These obstacles created unnecessary troubles in the implementation of international protection tools. Furthermore, the development of these policies and legal frameworks fell far short of being an effective or fair approach. Nevertheless, in September 2020, the European Commission presented a New Pact on Migration and Asylum (NPMA), which proposed a new holistic mechanism aiming at providing a new framework to respond to the new challenges and opportunities created in part by Covid-19 and other challenges related to migration and asylum flows.

The case of Calais refugee camp and the impact of Covid-19

The formation of camps has been the MbS’s unofficial answer to the so-called ‘migration crisis in 2015 (Davies 2015: 1). An example of this more than questionable management of migration flows was the creation of refugee self-settlements in Northern France, around the town of Calais, and the brutal interventions of the French authorities in April 2015. For further information about the history of the settlements created in Calais and in surrounding areas, have a look at the report published by Refugee Rights Europe (2020).

As a consequence of these violent interventions, around 1500 migrants and asylum seekers were forced to leave their encampments. Many of these people forcibly resettled in another area at the east of Calais, as well as in other regions of France. However, a new self-settlement was built under the name of the ‘new Jungle’. The ‘new Jungle’ was located on a former industrial landfill site adjacent to a chemical factory and to a motorway. There was only one water point serving the entire population, forcing many families to go out in search of water to bring it back to their self-built shelters (Davies, 2015: 1).

This new settlement has been dismantled, burned, and destroyed several times. Probably, the best-known events were those that occurred during 2016, when the French authorities, along with British complicity and European inaction, created chaos without remedying the roots of the problem. For further information, see the article ‘Not all wars and not all victims: Uncertain refugee in Calais’ by Peter Blodau & Elle Kurancid (2016); or the report published by Help Refugees, Refugee Rights Europe, Refugee Women’s Centre, Refugee Youth Service, Safe Passage (2019) ‘Left Out in the Cold. The Vulnerable Children on Britain’s Doorstep and the Urgency of Post-Brexit Family, Reunion Rules’.

Already in 2015, Intercept reported that; ‘the French and British governments have poured millions of dollars into extra riot police, dogs, tear canisters, floodlights, infrared cameras, (…) while neglecting to provide appropriate medical support, sanitation, meals, running water, or clothing’. A more recent example of how political decisions made in the UK affect the French government’s decision-making is mentioned by Matthieu Tardis, an expert on migration policy at the French Institute of International Relations in Infomigrants’ online newspaper (2020); ‘previous bilateral agreements – estimated to have cost Britain at least 100 million euros – to fund increased border security on the French side to prevent undocumented migrants from reaching the UK’. According to the report published by Refugee Rights Europe, the UK’s so-called ‘juxtaposed border arrangements and the tightening of security measures have led to the creation of what could be called a “bottle-neck” scenario (2020, p7; Crawley 2010).

In the middle of these uncoordinated and unjust responses, numerous NGOs and local associations such as Refugee Community Kitchen (see https://refugeecommunitykitchen.org/); Care4Calais (see https://care4calais.org/); Refugee Women’s Centre (see http://refugeewomenscentre.com/); Action Calais (see https://www.calaisaction.com/); or Utopia 56 (see http://www.utopia56.com/en) , have struggled to fill the gaps in assistance and protection that states at the national level, or supranational organisations such as the EU, fail to provide.

Despite all attempts to prevent the regrouping of migrants in the area north of Calais, more specifically in the Jungle, thousands of refugees and migrants including children continue to live in conditions of increasing squalor and deprivation. In fact, from 1st January to 31st December 2019 alone, there were around 961 evictions from informal settlements in Calais. This corresponds to an increase of almost 112% compared to the number of evictions carried out in 2018 (L’Auberge des Migrants, Human Rights Observer & Help Refugees 2019, p21). In this context, the fate of many unaccompanied and refugee children has fallen into the political fight between France and the UK, who continue to blame each other for their incompetence (Ibrahim, 2020: 2). In the meantime, aid workers and NGOs offer assistance that is very limited, and sometimes even criminalised.

The ‘criminalisation of solidarity’, according to the report published by RESOMA (Research Social Platform on Migration), refers to the increased surveillance of people assisting migrants, including journalists, priests, aid workers, volunteers, and NGOs (2020). The World Report 2021 published by Human Rights Watch alleges that in Calais, NGOs providing aid to migrants and asylum seekers have been subjected to harassment and abuse by the French authorities. On 10th September of 2020, the prefect of Pas-de-Calais banned any free distribution of drinks and food in certain areas of the city centre and some municipalities of Calais (Boussemart, 2020). Indeed, in France, the ‘délit de solidarité’, which is related to the facilitation of border crossings, remains illegal. Hence, any assistance to irregular entry remains criminalised regardless of its purpose, even if such aid was provided for humanitarian purposes (Ferstman, 2019: 27, 28). For more information on this issue, see Dr. Carla Ferstman report, published in the Expert Council on NGO Law CONF/EXP (2019)1, ‘Using criminal law to restrict the work of NGOs supporting refugees and other migrants in Council of Europe Member States’.

However, this seems to be only the beginning of a horrible story. On 31st January 2020, the UK officially left the EU, and on 16 March 2020, French President Emmanuel Macron announced the first national lockdown after the arrival of Covid-19 in Europe (Momtaz, 2020). These two elements had a profound impact on the lives of the Jungle’s inhabitants, workers, and volunteers. This context further slowed down the creation of safe passage for minors to find refuge in the UK (Wallis, 2020). In addition, the organisations working on the ground did not receive the necessary support to manage the terrible situation faced by thousands of people in and around Calais.

In an article written by Annie Kelly in The Guardian (2020), warned that Covid-19 was quickly spreading through the camp. Kelly also highlighted that Care4Calais was the only remaining NGO providing emergency aid to migrants and refugees in the makeshift camps and that over 1000 people did not have access to adequate sanitation, water supplies or food. Furthermore, several reports underline the escalation of police violence against the displaced communities in Calais since the outbreak of the pandemic (Evans-Jesra, 2020; Transnational Institute, 2020).

The combination of these factors mentioned above created unprecedented risks of abuse to unaccompanied and refugee children (Bulma, 2020). Already in February 2019, Médécins Sans Frontières (MSF) warned that ‘people were denied the opportunity to apply for asylum in France, and minors are particularly not considered as such; indeed, they are routinely turned away and push it back to Spain, instead of offering them protection as the law requires’. MSF and the organisation Comede alerted that the lockdowns implemented since the advent of the pandemic had affected ‘young unrecognised migrants ten times as hard as the rest of the population’ (Carretero, 2021). In a report published in June 2020, MSF warned of the many “negative” consequences of these lockdowns on the mental health of young people, including fearful increases in suicidal thoughts, anxiety, and a wide range of sleep disorders (this data was collected from the first lockdown 17 March to 11 May 2020). All the young people interviewed were waiting for their status as minors to be confirmed, in order to gain access to French child protection services. However, while these young people were waiting for a response, some of them were receiving help from local charities, but most of them were living on the streets.

In response to this untenable situation regarding the inadequate management of Covid-19 in Calais, organisations on the ground and other supporters of the cause sent an open letter to the French authorities asking for urgent measures to be taken to protect the migrants who were in a situation of total vulnerability (Ugolini, 2020). Approximately two weeks later, on the 27th of March 2020, another Open Letter was submitted to the EU, the United Nations (UN), and the Council of Europe (Auberge des Migrants, Help Refugees, Human Rights Observers, et al. 2020). However, the response of the local authorities was unfavourable to these requests.

To conclude this section, it is worth noting the lack of quantitative data on the minors affected. The monitoring that the French state, the EU, or other international organisations have been doing on this issue, especially since the beginning of the pandemic, is insufficient or non-existent. As the ‘Cour de Comptes’ (Court of Auditors) emphasised in a publication dated 17 December 2020, there is ‘a lack of statistics and knowledge of the young people concerned’. In this same report, Cour de Comtes mentions that the phenomenon of unaccompanied minors has not been a priority subject either by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) or by Eurostat – the latter has not included data in its annual surveys mainly because of the differences in treatment and definition of unaccompanied minors by MbS (Cour de Compte, 2020: 5). The absence of ‘solid information’ is also highlighted in a report published by UNICEF France on 10 March 2021, especially because the generation of uncertain or ‘not very objective’ information can have a negative impact on minors’ life.

Conclusion

The multidimensional aspects of migration management seem to have no simple solution; and this can be seen in the numerous differences between (in) formal refugee camps and self-settlements, as well as in the several tools and methods used to control or organise them. This article provides an overall view of how the protection of the human rights of the inhabitants of (in)formal refugee camps or self-settlements should be managed. Another essential point of this short essay is the explanation of the different legal statuses of minors based on their contexts. Finally, the example of the Calais refugee camp, also known as “the Jungle”, puts the theoretical basis of the article into perspective in a practical case.

One of the main insights gained after researching the Calais case is that there is a significant difference between theory and its implementation on the ground. The main observations which can be drawn from the chapter dedicated to the Calais case are the following: (i) the difference between the theoretical basis and the implementation of policies that ensure human rights; (ii) the absence of international or supranational organisations on the ground; (iii) the precariousness and insecurity of local organisations and NGOs; (iv) the lack of protection of the basic rights of minors living in the Calais settlements; (v), the violence of the control strategies and methods implemented by the French state, both local and national authorities, have only served to worsen the living conditions of the inhabitants of the self-settlements located in the area; and finally (vi), the direct or indirect involvement of the UK, as well as the arrival of Covid-19 in Europe, has further degraded the lives of the inhabitants of the refugee camps in Calais.

However, this brief investigation also leads us to ask further questions: although French and British non-state associations and charities are doing their best to cover the basic needs of the inhabitants of the self-settlements of Calais, it seems not to be enough. Thus, could a better integration of the migrants’ communities living in refugee camps or self-settlements into local life enhance the effectiveness of associations working on the ground? Could the intervention of supranational organisations such as the European Union improve the life’s condition of the inhabitants of the self-settlements located in Calais and Grande-Synthe? What has been the role of social media in the development of the settlements in Calais and Grande-Synthe? Hopefully, we will be able to continue writing on this topic and others that may be of interest to the EST audience.

Bibliography

Ammairati A. (2015) ‘What is the Dublin Regulation?’, Open Migration. https://openmigration.org/en/analyses/what-is-the-dublin-regulation/

Auberge des Migrants, Help Refugees, Human Rights Observers, et al. (2020) ‘Open Letter to the European Union, the United Nations and the Council of Europe regarding the urgent need for an adequate Covid-19 response in Northern France’. https://refugee-rights.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Open-Letter-Urgent-need-for-an-adequate-Covid-19-response-in-northern-France.pdf

Bakewell O. (2014) Encampment and Self-Settlement. In E. Fiddian-Qasmiyeh, G. Loescher, K. Long and N. Sigona (red.). The Oxford Handbook of Refugee & Forced Migration Studies (pp 117-125.). Oxford, England:Oxford University Press.

Berthiaume C. (1994) ‘Refugees Magazine Issue 97 (NGOs and UNHCR) – NGOs: our right arm’. https://www.unhcr.org/publications/refugeemag/3b53fd8b4/refugees-magazine-issue-97-ngos-unhcr-ngos-right-arm.html?__cf_chl_jschl_tk__=4f4c269b41ce0bc469bf1aae62e81e14f11925df-1621258547-0-AaCCFzeSlejQ5wqy7Voumqf_J9ZrZtc90XPcV21o8SyoHUP9K-vq73raRTgtsIRNJ7Ui2fxx4qQPLv494fQEOdeD7Fy2eB_9l_BnQEGNaVOwD1Twah-qsXWOpw95SMq6ZzHblR_nEkEWOSHK7tGhzTHqWkzn3e2-LhMnlV4z4UDKsy0vQ2nFHsSU4tSBVxhPp8D7Ow81bDOWd9sdiHAj_0zOKmI9ixNjfwLQIImZIICzy8FrYReRUKkz-7gV5-_KNAKK3BX9a6vJZStwEqz_mnN3aWNmaCJ9k4HDkpUDF5IYGpkH4PhsGCukS6I-fbAjLJE2haa2SRSMHtc1vvkz6N_ke9vbrJT5cJSnfT8GrUad8F1eVJg5MxRSVS1ZZ5Y38ZBFBflbX1JRPL12uXTmMGqOQBFUDI_OeAAO0GJ9IYaa3G0QUw2JYQL7eb7JwH-BdILFD69OVs7glkDkyAHLw9zOALdVo8bNxajRJaVawNcMEERbsMQ7jy6lc9KlEWO-t14XdL_k1CBX2F47hAMIMbk

Blodau P. & Kurancid E. (2016) ‘Not all wars and not all victims: Uncertain refugee in Calais’ Le Monde Diplomatique.

Boittiaux C., MiraF. & Welander G. M. (2020) Refugees and displaced people: A brief timeline of the human rights situation in Northenr France, Refugee Rights Europe.

Boussermart A. (2020) ‘Calais : l’interdiction de distribution de repas aux migrants renouvelée et élargie au Beau-Marais’, La Voix Du Nord, (accessed 01/11/2021). https://www.lavoixdunord.fr/872689/article/2020-10-01/l-interdiction-de-distribution-de-repas-aux-migrants-calais-prolongee-et-etendue

Brown A. (2015) ‘The Jungle: During Paris Summit, Climate and War Refugees Continued to Perish’, The Intercept (accessed 31/10/2021). https://theintercept.com/2015/12/15/spurned-by-the-french-government-refugees-risk-death-to-reach-england/

Bulma M. (2020) ‘An extremely hostile environment’: Refugee children in Calais face unprecedented risk of abuse’, Independent. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/calais-child-refugees-children-channel-france-home-office-b555833.html

Carretero L. (2021) ‘Unrecognized young migrants: Hard hit by lockdowns in France’, Infomigrants. https://www.infomigrants.net/en/post/31684/unrecognized-young-migrants-hard-hit-by-lockdowns-in-france

Crawley H. (2010) ‘Chance or choice? Understanding why asylum seekers come to the UK’, Refugee Council.

Citizens Information, Dublin III Regulation (accessed 26/09/2021). https://www.citizensinformation.ie/en/moving_country/asylum_seekers_and_refugees/the_asylum_process_in_ireland/dublin_convention.html#

Cour de Compte (2020) ‘La prise en charge des jeunes se déclarant mineurs non accompagnés (MNA)’, Paris (accessed 27/09/2021). https://www.ccomptes.fr/system/files/2020-12/20201217-refere-S2020-1510-prise-charge-jeunes-mineurs-non-accompagnes-MNA.pdf

Davies T. (2015) ‘Geography, migration and abandonment in the Calais refugee camp’, Political Geography: Elsevier.

European Commission, ‘New Pact on Migration and Asylum’, (accessed 07/11/2021). https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/promoting-our-european-way-life/new-pact-migration-and-asylum_en

Evans-Jesra, J. (2020) ‘Covid-19 in Calais – a harsher hostile environment, Global Justice Now. https://www.globaljustice.org.uk/2020/05/covid-19-calais-harsher-hostile-environment/ Franceinfo (2020) ‘Coronavirus: quelles mesures l’État prend-il auprès des migrants à Calais et à Grande-Synthe?’, (accessed 26/09/2021). https://france3-regions.francetvinfo.fr/hauts-de-france/coronavirus-quelles-mesures-etat-prend-il-aupres-migrants-calais-grande-synthe-1802114.html

Ferstman C. (2019) ‘Using criminal law to restrict the work of NGOs supporting refugees and other migrants in council of Europe Member States’, Expert Council on NGO Law CONF/EXP (1). https://rm.coe.int/expert-council-conf-exp-2019-1-criminal-law-ngo-restrictions-migration/1680996969

Help Refugees, Refugee Rights Europe, Refugee Women’s Centre, Refugee Youth Service, Safe Passage (2019) ‘Left Out in the Cold. The Vulnerable Children on Britain’s Doorstep and the Urgency of Post-Brexit Family, Reunion Rules’. https://www.refugee-rights.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/RRE_LeftOutInTheCold.pdf

Homolová, A. (2021) ‘Lost in Europe’s data publication became worldnews’, Lost in Europe (accessed 07/11/2021). https://www.datawrapper.de/_/7Cscs/

Human Rights Watch (2021) ‘France: Events of 2020’, (accessed 01/11/2021). https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2021/country-chapters/france#26e077

Ibrahim, Y. (2020) ‘The Child refugee in Calais: from invisibility to the ‘suspect figure’’, Journal of International Humanitarian Action, 5:19.

ICRC (2004) ‘Inter-agency Guiding Principles on Unaccompanied and Separated Children’, Central Tracing Agency and Protection Division: Geneva.

Kelly A. (2020) ‘Covid-19 spreading quickly through refugee camps, warn aid Calais groups’, The Guardian, (accessed 26/09/2021). https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2020/apr/09/covid-19-spreading-quickly-though-refugee-camps-warn-calais-aid-groups

Lawrence J, Dodds A, Kaplan I, Tucci M (2019) ‘The rights of refugee children and the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child’, MAPDI: Laws 8 (20): 4.

L’Auberge des Migrants, Human Rights Observer & Help Refugees (2019) Annual Report 2019: Observation of Human Rights, Violations at the UK-French Borders, Human Rights Observers (HRO).

MacGregor M. (2020) ‘France to UK: Why do migrants risk the Channel crossing?’, Infomigrants, (accessed 31/10/2021). https://www.infomigrants.net/en/post/27398/france-to-uk-why-do-migrants-risk-the-channel-crossing

Martin D. (2014) ‘From spaces of exception to ‘campscapes’: Palestinian refugee camps and informal settlements in Beirut’, Political Geography (44), 9-18.

Médécins Sans Frontières (2020) ‘Migrants trapped in relentless cycle of rejection on French-Spanish border’, MSF. https://www.msf.org/migrants-trapped-relentless-cycle-rejection-french-spanish-border-france

Médécins Sans Frontières (2020) Vivre le Confinement les Mineurs Non Accompagnés en Recours Face ‘A L’Epidémie de Covid-19, Avril 2021. https://www.msf.fr/sites/default/files/2021-04/Rapport%20de%20plaidoyer%20MSF%20Mission%20France_Vivre%20le%20confinement.%20Les%20MNA%20en%20recours%20face%20%C3%A0%20l%27%C3%A9pidemie%20de%20Covid-19_Avril%202021..pdf

Momtaz R. (2020) ‘Emmanuel Macron on coronavirus: ‘We’re at war’’, POLITICO, (accessed 26/09/2021) https://www.politico.eu/article/emmanuel-macron-on-coronavirus-were-at-war/

RESOMA (2020) ‘The criminalisation of solidarity in Europe’, EU Horizon 2020 Programme, https://www.migpolgroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/ReSoma-criminalisation-.pdf

OHCHR, Convention on the rights of the child (accessed 07/11/2021). https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/crc.aspx#:~:text=Article%203,1.,shall%20be%20a%20primary%20consideration

Paton E. & Boittiaux C. (2020) ‘Facing Multiple Crises: On the treatment of refugees and

displaced people in northern France during the Covid-19 pandemic, Refugee Rights Europe. https://refugee-rights.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/facing-multiple-crises-report.pdf

Sang D. (2017) ‘Calais Jungle Camp: Mission Accomplished?’ HuffPost (accessed 26/09/2021). https://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/dorothy-sang/calais-jungle-camp-refugee_b_12670136.html

Schmidt A. (2003) FMO Thematic Guide: Camps versus Settlements. https://www.alnap.org/help-library/fmo-thematic-guide-camps-versus-settlements

Stevens D. (2016) ‘Rights, needs or assistance? The role of the UNHCR in refugee protection in the Middle East’, The International Journal of Human Rights 20(2), p 264-283.

Strootbants J. (2021) ‘En trois ans, plus de 18 000 mineurs étrangers ont disparu en Europe’, Le Monde (accessed 07/01/2021). https://www.lemonde.fr/international/article/2021/04/19/en-trois-ans-plus-de-18-000-mineurs-etrangers-ont-disparu-en-europe_6077328_3210.html

Transnational Institute (2020) ‘Covid-19 and Border Politics’; Border Wars Briefing 1. https://www.tni.org/files/publication-downloads/tni-covid-19-and-border-politics-brief.pdf

Ugolini S. (2020) ‘Coronavirus : des associations réclament des mesures “urgentes” pour les migrants’, RTL France. https://www.rtl.fr/actu/debats-societe/coronavirus-des-associations-reclament-des-mesures-urgentes-pour-les-migrants-7800268558

UNHCR, UNICEF, & IOM (2018) ‘Refugee and Migrant Children in Europe. Accompanied, Unaccompanied and Separated: Overview of Trends, January to December 2019. https://www.unhcr.org/cy/wp-content/uploads/sites/41/2020/06/UNHCR-UNICEF-and-IOM_Refugee-and-Migrant-children-in-Europe-2019.pdf

UNHCR, UNICEF, IOM (2020) Refugee and Migrant Children in Europe Accompanied, Unaccompanied and Separated, January – June 2020. file:///C:/Users/moren/OneDrive/Escritorio/UNHCR-UNICEF-IOM%20Factsheet%20on%20refugee%20and%20migrant%20children%20Jan-June%202020.pdf

UNHCR (2021) Camp coordination and camp management (CCCM). https://emergency.unhcr.org/entry/42974/camp-coordination-camp-management-cccm

UNICEF, ‘What is the Convention on the Rights of the Child?’ https://www.unicef.org/child-rights-convention/what-is-the-convention

UNICEF (2021) ‘Un Rapport Parlementaire sur les mineurs non accompagnés qui inquiete vu sur’, (accessed 27/09/2021). https://www.unicef.fr/article/un-rapport-parlementaire-sur-les-mineurs-non-accompagnes-qui-inquiete

Wallis E. (2020) ‘post-Brexit Britain begins to close doors to unaccompanied children without relatives in the UK’, Infomigrants. https://www.infomigrants.net/en/post/29880/post-brexit-britain-begins-to-close-doors-to-unaccompanied-children-without-relatives-in-the-uk

The ’Ndrangheta’s Infiltration and Threat to European Institutions

The ’Ndrangheta’s Infiltration and Threat to European Institutions  From Paper to Practice: How Grassroots Norms Undermine Gender Rights in Pakistan

From Paper to Practice: How Grassroots Norms Undermine Gender Rights in Pakistan  Exploited Childhoods: The Role of Global Corporations in Perpetuating and Mitigating Child Labour

Exploited Childhoods: The Role of Global Corporations in Perpetuating and Mitigating Child Labour  Human Rights Challenges in Addressing SLAPPs in Media, NGOs and Journalism in the EU

Human Rights Challenges in Addressing SLAPPs in Media, NGOs and Journalism in the EU