Written by Zoe Nakoma Hartwig and edited by Sara Lolli

Introduction

The European Peace Facility (EPF) has gained substantial momentum since 2021 as the instrument that enabled the European Union (EU) for the first time to send lethal weapons to a third country, Ukraine. In two years, the EPF brought the EU’s security and defence development forward, deserving a comprehensive analysis at this point. This article seeks to explore the various perspectives on the EPF to provide an analysis of not only the positive (the good) and the negative (the bad) impacts but also the fundamental shifts (the ugly?) shaping the EU’s identity and influence on global security.

The Good

The EPF has significantly broadened the EU’s range of instruments to promote its strategic objectives on a global scale, thereby becoming a ‘game-changer’ (Tomat, 2021). It has emerged as a crucial off-the-budget fund providing military assistance to third countries (non-EU) and supporting EU Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) missions. This fund served as the solution to a legal block for financing military equipment, including lethal weapons, and replaced the Althena Mechanisms and prior African Peace Facility (APF). The primary rationale for removing this legal block was to improve its security assistance, filling the gap between technical support and much-needed military equipment for an all-encompassing integrated support to partners (Maletta and Heau, 2022; Shiferaw and Huack, 2022). Prior, the APF was almost entirely a budgetary support mechanism where the EU had limited say, paying mostly operational and salary costs of the African Union’s missions (Dinca, 2023). Thus, with the EPF, the EU has successfully overcome a legal barrier and increased its control over funding and security assistance.

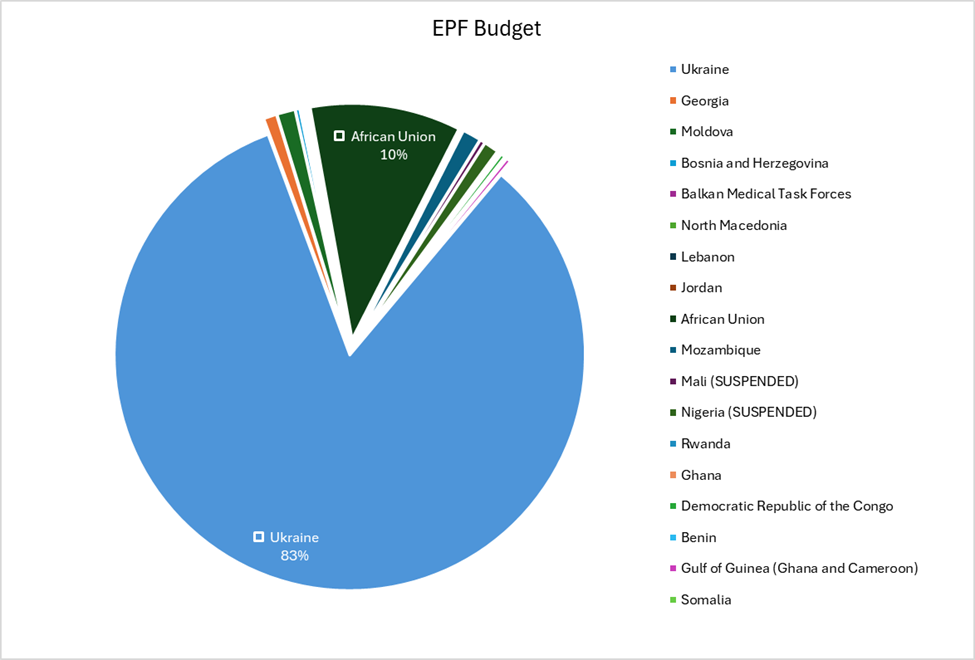

As a result, the European Peace Facility enables the EU to act independently, improving its capacity to support third countries and attain the ability to participate and influence international security. The European Union’s Global Strategy (2016) sought an EU with greater flexibility and tools to achieve strategic goals as such analysts have already described the EPF as an effective geopolitical tool (Dinca, 2023; Shiferaw and Huack, 2022; Karjalainen and Mustasilta, 2023). As evident, the EPF is used to reinforce countries against terrorism and to minimise migration, two major objectives of the EU (Dinca, 2023). However, its most notable application is in Ukraine, with a training mission and other assistance topping up to almost six billion euros (see Graph 1). Yet, the support for Ukraine is unique as the military demand is high and aligns seamlessly with EU security objectives (Karjalainen and Mustasilta, 2023). The significance of US support to Ukraine, member states’ limited commitments, and the restricted military-industrial complex of Europe are all not answered by the EPF (Tchakarova and Hrabina, 2023). Thus, realist analysts welcome the EPF but are uncertain of the effective contribution to EU defence and security capabilities when those fundamental restrictions are left unanswered (ibid.; Dumoulin et al., 2023; Grand, 2023).

Graph 1: Budgetary distribution of the EPF until November 2023 adapted from European Peace Facility Factsheet (EEAS, 2023)

However, one cannot overlook the success of the EPF for Ukraine. The budgetary ceiling of the EPF has been raised multiple times to enable greater support, and within a year of its establishment, the EU supplied funding for lethal weapons (Finable, 2023; PAX, 2023). While it is undeniable that the invasion of Ukraine was an exceptional circumstance, it did demonstrate the true purpose of the EPF – to serve as a more effective and rapid response tool to support the EU’s security strategy (Karjalainen and Mustasilta, 2023; Schmidt, 2022; Shiferaw and Huack 2022). Moreover, within its first two years, it has supported almost twenty countries (see Graph 1). This is substantial given the EU expectation-capacity gap, as described originally by Christopher Hill and followed by other scholars arguing the lack of resources and outcomes in contrast to heightened status and policy proposals made by the EU’s foreign policy actors (Bendiek et al., 2020). Although the European Peace Facility continues several capacity-building projects and most of its support still goes to traditional partners in Africa, with Ukraine as an exception, noteworthy developments include a heightened commitment from member states, a leading role played by the European External Action Service and an expansion of the EU operational toolbox.

The Bad

While the EPF has successfully pulled funds for its security assistance, coordination remains an issue, and the goal of an integrated security strategy with a predictable funding stream has yet to be fully fulfilled. Firstly, Bergmann (2023) questions the exclusive security assistance of the EPF that sidelines other policy instruments in support of capacity-building within the same target countries. This is at odds with the EU’s aim of pursuing an integrated approach in external actions, such as in the new whole-encompassing development instrument, the Global Europe-NDICI. For instance, according to PAX (Tschomba, 2023), the prior African Peace Facility’s success was primarily due to its layered response, expanding early response mechanisms, capacity-building initiatives, and military support. These analysts would generally disagree with exclusive security assistance, but to depart from this bias, having an exclusive military financing system would require much more coordination with other funding instruments and EU projects. To offer a balanced argument, Tomat (2021) would contend that the EPF does fill the prior military/security assistance gap in response to conflict, thus demonstrating a truly integrated approach.

Secondly, achieving coordination and commitment is an ongoing challenge for the EU, as it was already seen within the EPF’s framework. In March 2022, EU High Representative Josep Borrell announced that the EU would be supporting Ukraine with fighter jets, which was not agreed upon by the EU member states (Schmidt, 2022). Additionally, Ireland, Malta, and Austria abstained from the transport of lethal weapons to Ukraine (ibid.). It highlights the ongoing coordination struggles within the EU and emphasises diverging strategic cultures. But even so, the foreign policy shift witnessed after the invasion of Ukraine is beginning to show some cracks, even amongst supportive member states. Thus, as realist sceptics of the EU’s foreign policies indicate, despite this development in foreign policy integration, the member states must still navigate their political landscape to authorise, conduct, and regulate their contributions (Tchakarova and Hrabina, 2023; Maletta and Heau, 2022).

Thirdly, an additional rationale for the EPF was to provide a funding stream that was predictable and sustainable, and that would foster stronger partnerships with third countries (Furness and Bergmann, 2018). However, with the invasion of Ukraine, this was overturned. As mentioned, the budgetary ceiling was broken several times, which Maletta and Heau (2022) argue creates uncertainty in the funding allocation and budget. Particularly for the EU’s key partner, the unpredictability does not align with the primary goal of the African Union (AU), which is to secure stable and sustainable funding for their missions (Dinca, 2023). While this may not be considered a major cause for concern, given that the EPF is meant to be a rapid response mechanism, the unpredictability stems from a lack of coordination and disagreements. For example, there have been delays and subsequent frustration over the reimbursement procedures to member states, as support for Ukraine was initiated swiftly before detailed discussions took place (Maletta and Heau, 2022).

The Ugly?

The EPF has raised concerns, especially from both humanitarian organisations and analysts (e.g. PAX, Altamimi, 2022), regarding the use of lethal weapons and the risk of arms diversion, which may exacerbate security challenges rather than mitigate them. Although the EPF’s main rationale is to overcome the EU’s own legal restrictions, it still has a complicated legal framework that mirrors the international debate on funding arms, particularly to regions in conflict (ibid.; Maletta and Heau, 2022). The EPF does mention international human rights and humanitarian law, but it is limited. For example, it does not reference the state’s (EU and Member states’) international responsibility or the Arms Trade Treaty (Altamimi, 2022). However, even without explicit mention, the Member States’ and the EU’s policies and actions are bound by international law (ibid.). Nevertheless, it does reveal a lack of emphasis on human rights and a legal complexity that the EU has failed to address.

In addition, the risk assessments conducted to uphold human rights lack transparency or proper attention (Maletta and Heau, 2022; Altamimi, 2022; Tschomba, 2023). A leaked risk assessment report for Ukrainian assistance revealed that the EU’s approach towards such evaluations lacks the necessary level of gravity (ibid.). Moreover, recent interviews conducted by PAX (ibid.) with local civil society organisations in multiple African countries showed that they were not well-informed about the EPF and were not consulted for the risk assessment process. Although the risks and, most likely, the liability come down to member states, the lack of transparency within the EU is concerning (Rutitigliano, 2022). It is questionable whether the legal maze of international arms transfer would have been dealt with through the establishment of the EPF, but as the EU strongly upholds its values in human rights, the regulations and risk assessment are below expectations.

The current EU-African Union relations are also below expectations, and the EPF has failed to align with analysts’ recommendations for revitalisation (Shiferaw and Huack, 2022; Bergmann, 2023; Dinca, 2023). The prior funding tool, the African Peace Facility, was born out of a request from the African Union, and it became a vital tool in the EU-AU security relationship (ICG, 2021; Dinca, 2023). However, with the EPF, the EU can bypass the African Union’s consultation and fund African national armies. Making matters worse, the EPF was not an essential aspect of EU-AU Summits, and the EPF does not reflect the AU’s goal to secure sustainable funding for its security operations. It symbolises the EU’s retreat from the African Union and the AU’s fragmentation (Shiferaw and Huack, 2022). Even though the African Union still makes up most of the EU’s financial contribution to Africa (See Graph 1), as Shiferaw and Huack (2022) argue, the swift commitment of the EU to Ukraine highlights that where there is a will, there is a way, casting a shadow on EU-African relations.

Last but not least, the European Peace Facility is a firm part of the EU’s strategic compass to enable ‘strategic competition’ and ‘expands the EU’s ability to provide security for its citizens and its partners’ (EEAS, 2021). The transition from a regional African focus to a global facility, coupled with the active pursuit to tackle issues related to terrorism and migration, firmly positions the EU’s internal security objective at the core of the EPF (Dinca, 2023). While the EPF is seen as a positive stride towards a more cohesive foreign and security policy, it has encountered criticism from some quarters.

Some analysts and humanitarian organisations (Shiferaw and Huack, 2022; Dinca, 2023; Karjalainen and Mustasilta, 2023; Tschomba, 2023) argue that the EPF is not the appropriate response to civilian crises and conflicts. The EPF has been criticised for abandoning the development objectives of its prior instrument and, more widely, as a foreign policy approach. Thus, this raises concerns among humanitarian organisations about the effectiveness of a security-focused approach in promoting human security (ICG, 2021; Safterworld, 2019; Tschomba, 2023). It signals a securitised or even militarised approach to conflicts that only addresses the symptoms (e.g. terrorism) and not the drivers of conflict and crisis (e.g. economic instability) (ibid; Bergmann, 2023). This shift in approach also marks a departure from the EU’s traditional role as a civilian power in maintaining peace (ibid.). Karjalainen and Mustasilta (2023) indicate that even as the EPF initially emphasised conflict prevention, in 2023, this was dropped in favour of ‘security partnerships.’ This reflects a significant trend within the European Union’s foreign and security policies of subordinating development to security interests and securitising relations.

Conclusion

‘No other project stands as much for the EU’s shift from a peace project to a military power as the EPF’ (Schmidt, 2022). This illustrates the shift observers see in the European Peace Facility, which is supported by the increasing budget, the speed of resolutions and the lethal weapon support towards third countries. For an organisation that suffers from the expectations-capacity gap, this symbolises commitment. The EPF has successfully been established to support more than twenty countries in two years, and, in particular, it was the key instrument in the European support of Ukraine. However, it still suffers from a lack of coordination and secondary consequences, and fundamental questions persist about the EPF’s strategy for achieving security. It puts this funding instrument at a crossroads between the EU’s geopolitical interests and normative values.

___

Bibliography

Altamimi, A. M. (2022). The European Peace Facility and the UN Arms Trade Treaty: Fragmentation of the International Arms Control law? Journal of Conflict and Security Law. 77 (3): 411-437. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1093/jcsl/krac024

Bergmann. J. and Mueller, P. (2021). Failing forward in the EU’s common security and defence policy: the integration of EU crisis Management. Journal of European Public Policy, 28(1): 1669-1687. Retrieved from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/epdf/10.1080/13501763.2021.1954064?needAccess=true

Bergmann, J. (2023). Heading in the Wrong Direction? Rethinking the EU’s Approach to Peace and Security in Africa. SWP. 07/2023. Retrieved from: https://www.swp-berlin.org/publikation/mta-spotlight-26-the-eu-should-rethink-its-approach-to-african-peace-and-security

Bendiek, A., Alander, M., and Bochtler, P. (2020). CFSP: The Capability-Expectation Gap Revisited. SWP. Comment 2020/C 58. Retrieved from: https://www.swp-berlin.org/10.18449/2020C58/

Dinca, A. (2023). The European Peace Facility in action: rethinking EU-Africa Partnership on peace and security? Political Studies Forum, 4(1). Retrieved from: https://www.semanticscholar.org/reader/40f7eed25e6511c3f9952e204a0962e98be8edb4

Dumoulin, M., Friis, L., Gressel, G. and Litra, L. (2023). Sustain and prosper: How European can support Ukraine. European Council of Foreign Relations. Policy Brief. 08/2023. Retrieved from: https://docs.google.com/document/d/10Xro7WBopN94y_yRcpYl72LDy15INYHsc1rQ6kLsa3o/edit

EEAS (2023). The European Peace Facility Factsheet, EEAS. November 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/2023/EU-peace-facility_2023-11_0.pdf

EEAS (2021). European Peace Facility. EEAS. August 2021. Retrieved from: https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/european-peace-facility_en

Grand, G. (2023). A question of strategic credibility: How European can fix the ammunition problem in Ukraine. European Council of Foreign Relations. Commentary. 04/2023. Retrieved from: https://ecfr.eu/article/a-question-of-strategic-credibility-how-europeans-can-fix-the-ammunition-problem-in-ukraine/

International Crisis Group (ICG) (2021). The Evolution of EU Funding for Africa Peace and Security. How to Spend It: New EU Funding for African Peace and Security. International Crisis Group. Report N°297. Retrieved from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep31444.5

Karjalainen and Mustasilta (2023). European Peace Facility: from a conflict prevention tool to a defender of Security and Geopolitical interests. TEPSA. Briefs 05/2023. Retrieved from: https://tepsa.eu/analysis/european-peace-facility-from-a-conflict-prevention-tool-to-a-defender-of-security-and-geopolitical-interests/

Maletta, G. and Heau, L. (2022). Funding Arms Transfer through the European Peace Facility: Preventing Risks of Diversion and Misuse. SPIRI. 06/2022. Retrieved from: https://www.sipri.org/publications/2022/policy-reports/funding-arms-transfers-through-european-peace-facility-preventing-risks-diversion-and-misuse#:~:text=In%20addition%2C%20through%20the%20EPF,diverted%20to%20unauthorized%20end%2Dusers.

Furness, M. and Bergmann, J. (2018). A European peace facility could make a pragmatic contribution to peacebuilding around the world, Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE) Briefing Paper, No. 6/2018. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.23661/bp6.2018

Finable (2023). The Council of the EU tops up the European Peace Facility financial ceiling by an additional €3.5 billion, FINABLE. 17 July 2023. Retrieved from: https://finabel.org/playing-the-long-game-hungarian-parliament-continues-to-delay-swedens-nato-accession-bid-2/

Tschomba, P. (2023). Two years European Peace Facility. PAX. 06/2023. Retrieved from: https://paxforpeace.nl/publications/two-years-european-peace-facility/

Rutitigliano, S. (2022). Accountability for the misuse of proposed weapons in the framework of the new European Peace Facility. European Foreign Affairs Review. 27 (3): 401–416. Retrieved from: https://kluwerlawonline.com/journalarticle/European+Foreign+Affairs+Review/27.3/EERR2022029

Shiferaw, L. T. and Huack, V. (2022). The War in Ukraine: Implication of for the Africa-EUrope Peace and Security Partnership. Strategic Review of Southern Africa, 44 (1): 93-110. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.35293/srsa.v44i1.4071

Schmidt, N. (2021). The European Peace Facility, an unsecured gun on EU’s table. Investigate Europe. 29 March 2022. Retrieved from: https://www.investigate-europe.eu/posts/european-peace-facility-controversy

Tomat. S. (2021). EU Foreign Policy Coherence in Times of Crises: The Integrated Approach. European. Foreign Affairs Review. 26 (1): 149–156. Retrieved from: https://kluwerlawonline.com/journalarticle/European+Foreign+Affairs+Review/26.1/EERR2021012

Tchakarova, V. and Hrabina, J. (2023). State your case: the European Union needs to embrace realism before it’s too late. The Defence Horizon Journal. 9 March 2023. Retrieved from: https://tdhj.org/blog/post/european-union-realism/

The geopolitical role of the Sahel: the influence of the EU and other Great Powers in the Malian crisis

The geopolitical role of the Sahel: the influence of the EU and other Great Powers in the Malian crisis  Is Nuclear Disarmament Still a Dream? The Third Meeting of State Parties in Perspective

Is Nuclear Disarmament Still a Dream? The Third Meeting of State Parties in Perspective  Strategic Saboteur: Hungary’s Entrenched Illiberalism and the Fracturing of EU Cohesion

Strategic Saboteur: Hungary’s Entrenched Illiberalism and the Fracturing of EU Cohesion  The invention of development: power, narrative, and the afterlife of Truman’s speech

The invention of development: power, narrative, and the afterlife of Truman’s speech