Gordon Brown expressed a memorable idea during the referendum. He claimed that the E.U. should be

“A United Europe of States, not a United States of Europe.”

Britain could champion a looser arrangement of states on Europe’s ‘Outer’ periphery: The European Outer Area (EOA). This article is an exercise in realistic creativity; desperate times call for such measures. The peace and prosperity Europe has admirably built over the past 70 years risks being lost to mismanagement and to the forces of populism.

As will become clear, concepts such as ‘variable geometry’ are not new. Until just before the Maastricht Treaty, mainstream thinking held that all members should participate in all aspects of integration. This changed in the years after the Maastricht Treaty. From then on, there would be opt-outs for some countries from some aspects of integration. Known as ‘variable geometry’, this has been the natural progression of the European project thereafter. It is not the case that the E.U. is an obstinate, inflexible institution incapable of reform. Due to its history and nature, it is built on compromise. Therefore, it is not an impossibility that an Outer Area/form of sub-membership could be created and headed by Britain, as a result of Brexit.

Eurozone vs. The Rest

Central to this idea is that it would be the Eurozone vs. The Rest, which was discussed with interest at the Centre for European Reform (CER) previously. Britain could lead an ‘outer belt’ of countries currently within the E.U. that do not have the euro. This could include countries such as Bulgaria and Poland, whose economies are currently not suited to Euro adaption and are finding the Eurozone entry criteria too demanding.

They could be joined by members outside the E.U. altogether such as Switzerland and the EEA members Norway and Iceland.

A win-win situation, this would be seen favourably by the Eurozone, which would then be free to focus energies on overcoming its problems without having to incorporate the less-advanced Bulgaria or Poland.

It is true that integrationist appetite may have somewhat waned across the board. Banking unions, insurance deposit schemes and other integrationist measures that the Eurozone needs appear not to be on the table for the foreseeable future. Yet there are still politically innocuous integrationist advances that the Eurozone members could undertake. The Eurozone is inherently fragile, and a number of its member states have underperforming economies. Finding solutions to these problems should be the Eurozone and the E.U.’s priority before looking to expand.

The European Central Bank in Frankfurt has its work cut out – The Eurozone may have passed the worst, but it remains structurally flawed and dealing with chronically low growth.

For it to work, the ‘outer belt(s)’/non-euro members could only carry limited decision-making capacities as compared to Eurozone members, whom would likewise qualify for increased privileges.

Subsequently, key decision-making capacities could include the ability to allocate the headquarters of major E.U. bodies to Eurozone states. For example, Eurozone states should hold the right to move the European Banking Authority (EBA) out of London and to a Eurozone capital.

Privileges could include the increased directing of the EU’s energies to ‘expertise sharing’. The wealthier, northern European Eurozone states could undergo programmes of sending officials to help with structural reform and civil service overhaul in states where it has proven necessary (Germany has previously sent officials to help overhaul the Greek tax system). To tackle real problems such as these, practical solutions are needed. ‘Better Europe’ is needed as opposed to ‘More Europe’.

Other politically non-toxic advances in Eurozone could include the harmonisation of labour laws. This might ease the flow of labour from Eurozone areas of unemployment to Eurozone areas of labour shortages (from Portugal to Germany, for example).

Yet above all, a plan for the Eurozone is in order. Eurozone heads of state could meet every six months to discuss the Eurozone’s competitiveness, in let’s say, a ‘Eurozone Competitiveness Summit’ (ECS). This could include the wider E.U. heads of state (as it is in the interests of everyone that the Eurozone performs well).

A particularly interesting aspect of the Eurozone is that it inadvertently forces its members to adopt structural reforms. As part of this competitiveness building, Eurozone states tend to boost their comparative advantages, or put simply, to do best what they know how to do, as they cannot devalue. For example, Baltic states such as Estonia have become hubs for start-ups and high-end technological developments – the home of Skype. Greece clings to shipping and many types of tourism. Maybe this ought to be made an official strategy? Maybe Tallinn can become the European start-up capital? Maybe Greece can become the European shipping capital?

Such measures are taken by member states instead of simply devaluing the currency, which of course is not an option. With Britain gone and not standing in the way, Eurozone states may wish to officialise such an approach as they outline a plan for the years ahead.

The Rest

The ‘rascals’ should join forces to try to influence policy from the outer belt. Let’s say Britain, Poland, Norway, Switzerland, etc. convene in the form an ‘outer belt’ sub-committee.

Should Britain stay in the single market and have to adopt a Norway-style deal with the E.U., it would find itself in a situation whereby it is told what to do; this is politically untenable. An outer belt, however, with some say in policy-making, therefore offers a realistic solution. Little say would be better than no say.

Should Switzerland and current EEA members join this outer belt, they would gain some say alongside Britain. The little say that they gain would be better than no say, which they have had for decades under the EEA arrangement. True, EEA members (Norway, Iceland) and Switzerland, comply with EU legislation without having any say, in order to remain competitive with their neighbours. Ironically then, this sub-committee could now be their chance to improve their position with the E.U., which has never satisfied them. The Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker stated on December 9th,

“We have to invent a different orbit for those who don’t want to be a part of all the domains … This would not be a tragedy … It would be a chance. It would make things clearer”.

Wealthier members of this outer belt would have to forward budgetary payments, and/or military contributions, (and anything else to increase leverage), which could be offered in return for influence in single market rules.

Such changes do not fundamentally alter how the E.U. operates, yet they would shift the direction in which the E.U. is heading. These changes are achievable, and while some may consider implementation of the measures unrealistic, it should be noted that the E.U. reformed in such a ‘multi-currency’ direction under Cameron’s renegotiations – Britain and others would stand aside from further Eurozone integration. However, losing the referendum means this does not now hold. One former British minister summarised the situation,

“The old policy was to drive in the fast lane but as slowly as possible, holding everybody else back. Now the government is happy to pull over and let the others accelerate away, especially if that is deemed necessary to shore up the euro.”

This Outer Belt/EOA idea would be constructed along those lines: States that do not want to adopt the euro do not have to and do not try to. Those who wish to adopt the euro, meanwhile, have the opportunity – possibly the Czech Republic and Croatia. Yet the idea is different to this in that it does privilege Eurozone members in decision-making as previously discussed.

A multi-currency union also would accommodate less wealthy, non-Eurozone countries, which happens to be most of Eastern Europe. Euro adoption, in any case, is not suited to the current nature of economies such as Poland. Poland is a manufacturing base for much of Europe which relies on lower cost labour and cheap exports which are kept low by flexible exchange rates.

So, for the non-euro Poles and Bulgarians, the incentive would still be to join the euro (for higher real wages among other reasons), but they would lay off trying to enter momentarily. Should they wish to, they could re-initiate the Eurozone entry process at any point down the line and eventually join the inner Eurozone core.

Another benefit of such an arrangement would be that it could suit countries such as Ukraine or Serbia. Such countries face a long and difficult path to E.U. membership, and thus it may make sense for these countries not to be concerned with the extra demands of Eurozone membership.

Swedes and Danes

Two countries stand out as particularly problematic in regards to the multi-speed idea: Sweden and Denmark.

Sweden is a non-Eurozone member and it resembles Britain’s ‘so-so’ attitude to European integration (‘Lagom’ in Swedish.) However, Swedes are a highly educated bunch and for the most part, tend to be aware of the benefits that integration brings to Sweden. Swedish banks have a very large presence in the Baltic states. Sweden also is the 2nd biggest contributor to the E.U.’s budget; being side-lined would not bode well.

Denmark is a non-Eurozone member, given that its electorate rejected the euro in 2000. Thus, Denmark has pegged the Danish Kroner to the euro since 1992 for stability.

In any case, these two states could have specific ‘opt-outs’ of the euro. They could, furthermore, participate in the policymaking of the Eurozone states/Inner Belt and maintain their pledges to adopt the euro at some vague point in the future.

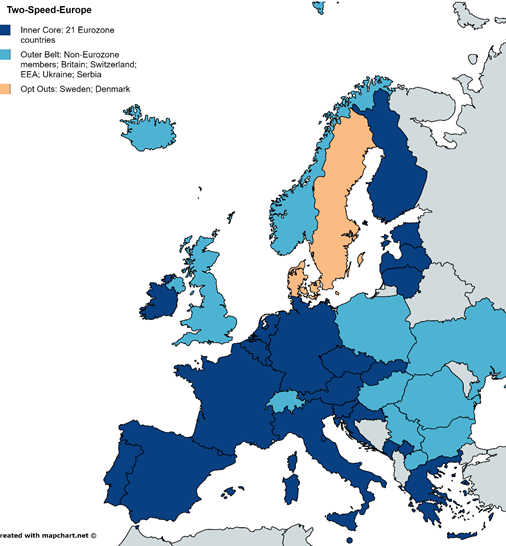

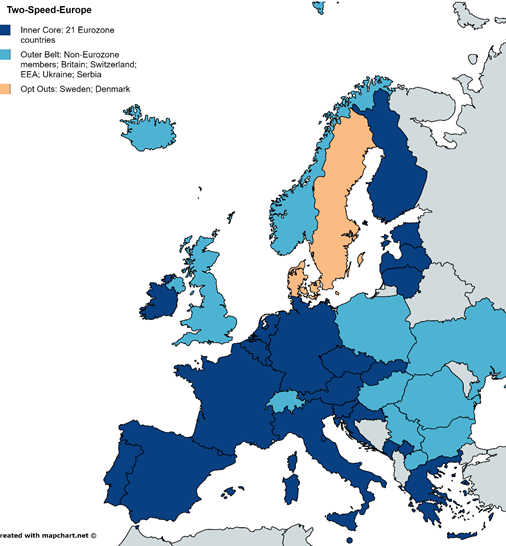

In due course, the unit may correspond roughly to the map below:

Figure 1: This figure includes extra members in the Inner Core/Eurozone; Non-EU Kosovo and Montenegro unilaterally adopted the currency; Croatia and the Czech Republic who may join in due course.

In dark blue, the 23 euro countries form the inner core:

Austria; Belgium; Croatia; Cyprus; Czech Republic; Estonia; Finland; France; Germany; Greece; Ireland; Italy; Kosovo; Latvia; Lithuania; Luxembourg; Malta; Montenegro; Netherlands; Portugal; Slovakia; Slovenia; Spain

In light blue, 12 countries form the outer core:

Britain; Switzerland

The EEA: Iceland, Norway, Liechtenstein

Non-Eurozone countries: Poland; Hungary; Romania; Bulgaria

Countries that could accede to the E.U. relatively soon: Ukraine; Serbia; Macedonia

In Pale Orange, 2 Non-Eurozone inner core members:

Sweden; Denmark

Of course, such an idea is not without its problems. Bulgaria, Romania, and Poland may not be eager to jump down a tier into the outer belt, where their voice is not as strong. Currently, however, as Cameron’s renegotiation are no longer applicable, the E.U. is not a multi-currency union. These countries’ voices may then be cast aside even if they will not be forced to join the euro any time soon, unless there is some sort of re-run of Cameron’s negotiations within the E.U.’s current framework.

Alternatively, a ‘hybrid tier’ or ‘middle tier’ could be created for these members. Ultimately, nevertheless, such discussion may be beyond the scope of this article.

At least, let’s see the idea as an athletics club: those most committed will become the best athletes, and this will earn them positions of responsibility. The coaches should be encouraging, but not overbearing. If they push athletes too hard, they will not want to come back, and if they are accommodating to those with different drives, they may be well-received by all of the athletes. Those ‘less committed’ may even decide to do more for the team at some point in the future.

Free movement

The free movement of people has been a hot topic, to say the least. I recently argued on VoteWatch Europe that the proposal of an emergency break system on E.U. immigration is not a non-starter. That’s to say, any given E.U. member state would carry the right to temporarily halt entry of E.U. citizens, perhaps in part. This could be done if there was clear evidence that E.U. immigration had compressed wages, put unduly pressure on public services, etc.

It is something which Switzerland has been striving to achieve since 2014. This proposal could finally gain traction through this ‘outer belt’ alliance.

So, Bulgaria, Romania, Poland, from where high levels of immigration are coming, may be more likely to agree to an emergency brake in return for continued British support against the all-integrationist Brussels. Warsaw has always seen London to be its key E.U. ally in this regard.

There would be widespread sympathy for an emergency brake, and it should be applicable to any member state, inner belt or outer belt.

Outlook

Like many, I believe that the Eurozone cannot avoid full fiscal and political union in the long run. The Republic of Ireland now appears to be returning to worryingly high-levels of growth – something which could quickly turn into a long-drawn recession in the event of another financial crisis.

However, for now it is about surviving, about muddling through. Now is not the time to push for federalism. Deeper political and fiscal integration of the Eurozone must wait for another day, for the next era of euro-enthusiasm, should there be one at all.

There lies an opportunity for Britain to draw upon latent political capital which they have in support from EEA and other members who share their concerns. They should use this like-mindedness for a comprehensive renegotiation and creation of a ‘second way’ in the European landscape.

The idea may be wishful thinking. It could be thoughtful wishing. Yet, those holding federalist ambitions should bear in mind that there needs to be something left to federalise. Should it not listen to the concerns of its members, the E.U. faces a serious prospect of disintegration. As phrased by the Dutch PM Mark Rutte recently on December 11th,

“We cannot push the project over the edge by pushing for more Europe … We are losing the population in the process.”

A line from Margaret Thatcher’s famous Bruges speech in 1988 speech puts it aptly,

“To try to supress nationhood and concentrate power at the centre of a European conglomerate … would jeopardise the objectives we seek to achieve.”

The two-speed, or multi-speed Europe, celebrating differences among states, could serve to build a unit that is truly ‘united in diversity’.

This article was written by Sean McLaughlin

Spain, Latin America and Caribbean Research Analyst at InframationGroup, based in London (http://www.inframationgroup.com/)

Northern Ireland Ambassador for the European Student Think Tank (https://europeanstudentthinktank.com/international-office/united-kingdom/)

Recent graduate of the University of St. Andrews (http://st-andrews.academia.edu/seanmclaughlin)

The ’Ndrangheta’s Infiltration and Threat to European Institutions

The ’Ndrangheta’s Infiltration and Threat to European Institutions  From Paper to Practice: How Grassroots Norms Undermine Gender Rights in Pakistan

From Paper to Practice: How Grassroots Norms Undermine Gender Rights in Pakistan  Exploited Childhoods: The Role of Global Corporations in Perpetuating and Mitigating Child Labour

Exploited Childhoods: The Role of Global Corporations in Perpetuating and Mitigating Child Labour  Human Rights Challenges in Addressing SLAPPs in Media, NGOs and Journalism in the EU

Human Rights Challenges in Addressing SLAPPs in Media, NGOs and Journalism in the EU