By Simona Torotcoi, Public Policy student at the Central European University and writer for the European Student Think Tank

“new [EU] members will not be allowed to lift their internal Schengen borders for many years, they will be required to reinforce their external borders, and they will wait for up to seven years after accession before their citizens enjoy the right to live and work anywhere in the EU”.[1]

When it comes to new members’ accession to the Schengen Area the interaction of the veto-players in deciding on these countries’ status is puzzling. More precisely countries such as Germany, France or The Netherlands and other Schengen members seem to present inconsistent behavior, attested by their contradictory statements made in short time periods regarding their official position towards the issue. The delay regarding the accession decision proves that there are controversial issues at the veto-payers level, a fact that reflects the level of trust and consensus among the members. Before exploring the main topic, this paper will present a short description of the Schengen area in terms of constituency, principles, membership and benefits. Further it will provide the main literature on EU and Schengen enlargement in Central Eastern European countries and try to explain veto-players’ behavior and its relevance to Bulgarian and Romanian Schengen “delay”.

The Schengen Area and its cornerstone principles

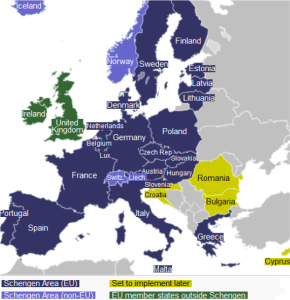

The Schengen Area is a group of twenty-six European countries that has abolished passport and immigration controls at their common borders. It functions as a single country for international travel purposes, with a common visa policy.

The Member Countries of the Schengen Area (Source: www.axa-schengen.com)

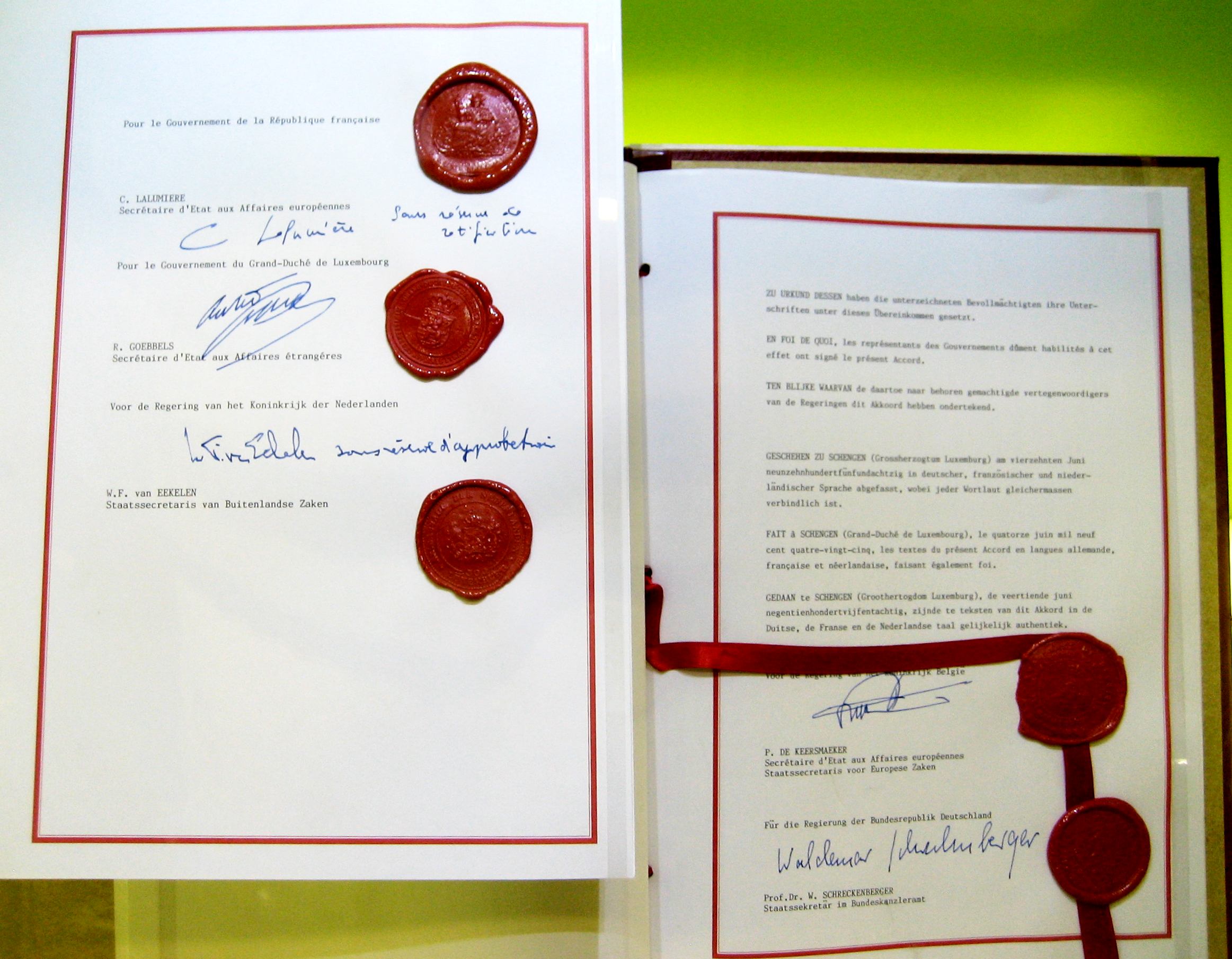

The Schengen Area represents a territory where the free movement of persons is guaranteed. The signatory states agreed to abolish all internal borders and have a single external border. Here common rules and procedures are applied with regards to visas for short stays, asylum requests and border controls. These rules are implemented based on the existing policies and regulations within each member state. Simultaneously, to guarantee security within the Schengen area, cooperation and coordination between police services and judicial authorities have been stepped up. It is relevant to mention that Schengen cooperation has been incorporated into the European Union (EU) legal framework by the Treaty of Amsterdam of 1997. However, not all countries cooperating in Schengen are parties to the Schengen area. This is either because they do not wish to eliminate border controls or because they do not yet fulfill the required conditions for the application of the Schengen acquis (e.g. Ireland, United Kingdom). According to Gaisbauer, Schengen started with an agreement of five member states in 1985 and was later incorporated into the Treaty of the European Union (TEU), an agreement which represents an effort to promote and strengthen principles such as freedom of movement and free circulation of goods and services.[2]

According to European Commission,[3] currently twenty-two of the European Union (EU) member states and the four European Free Trade Association (EFTA) member states are part of the Schengen Area. Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway, and Switzerland, four non-members of the EU, but member states of EFTA are part of the Schengen Area, while Monaco, San Marino, and the Vatican can be considered as de facto parts of the Schengen area as they do not have border controls with the Schengen countries that surround them. Ireland and the United Kingdom can maintain opt-outs.

Four EU member states, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus and Romania, are obliged to eventually join the Schengen Area. However, before fully implementing the Schengen rules, each state must have its preparedness assessed in four areas: air borders, visas, police cooperation, and personal data protection. The assessment process involves a questionnaire and regular visits by EU experts to selected institutions in the country under assessment. In order to become a full member it requires the agreement of all the other members and the relevant EU institutions.

Some of the benefits for being a Schengen member are the lift of controls between internal borders of member states and the creation of a single external border where checks are carried out according to a set of clear rules in the field of visas, migration, asylum, also measures related to police, judicial and customs cooperation.[4] Besides these benefits, joining the Area will have positive effects on state cooperation, free movement, trade opportunities, tourism and security, but it will also contribute to the country’s international reputation. However, as Gaisbauer claims, the benefits are mutual, the Schengen “club” provides certain network goods, which are “excludable but exhibit no rivalry in consumption but a kind of ‘inverse’ or ‘negative’ rivalry: the more members contribute to the production of and/or consume the good the higher the benefit for all”. Another reason why Western states may embark on Schengen or EU enlargement is due to the power of norm-based arguments through which they admit countries that share their liberal values.

Case study and research question

Joining the Schengen Area is not merely a political decision. Countries such as Bulgaria and Romania must also fulfill a list of pre-conditions among which include: the capacity to take responsibility for controlling the external borders on behalf of the other Schengen States and for issuing uniform Schengen visas; to efficiently cooperate with law enforcement agencies in other Schengen States in order to maintain a high level of security once border controls between Schengen countries are abolished; to apply the common set of Schengen rules (Schengen acquis), such as controls of land, sea and air borders (airports), police cooperation, and protection of personal data. Applicant countries undergo a “Schengen evaluation” before joining the Schengen Area and periodically thereafter to ensure the correct application of the legislation.

Bulgaria and Romania joined the EU in 2007, and in doing so they were also legally bound to join the Schengen Area, however the implementation has been delayed. They are not yet fully-fledged members of the Schengen Area and the border controls between them and the Schengen area are maintained until the EU Council decides that the conditions for abolishing internal border controls have been met. Bulgaria’s and Romania’s bids to join the Schengen Area were approved by the European Parliament in June 2011 but rejected by the Council of Ministers in September 2011, with the Dutch and Finnish governments citing concerns about shortcomings in anti-corruption measures and in the fight against organised crime. Concern has also been expressed about the potential influx of illegal immigrants through Turkey to Bulgaria and Romania and then to other Schengen countries. Although the original plan was for the Schengen Area to open its air and sea borders with Bulgaria and Romania by March 2012, and land borders by July 2012, continued opposition from the Netherlands in 2012 deferred the two countries’ entry. Current Schengen member states could veto Romania’s and Bulgaria’s membership if their capacity to control cross-border crime and other threats is judged to be inadequate.

By looking at the delayed accession of Bulgaria and Romania this paper investigates whether there is a level of mistrust between the Schengen Area veto-players and to what extent this delay is a result of a lack of confidence (the certainty that the partner will apply the rules effectively) between the member states. In order to answer this question, the focus of this research will be on the migration policy and different levels of interaction between the involved actors (between the core Schengen members (horizontal), between core and peripheral Schengen members (horizontal) and last but not least (vertical) between Schengen members and applicant countries).

Before analysing the decision making process in this regards, it is worth looking at countries such as Denmark, Ireland and United Kingdom, Iceland and Norway, which can be considered the agenda setters in this case. For example Denmark can choose whether or not to apply any new measures taken under the EC Treaty within the EU framework, even those that constitute a development of the Schengen acquis. Ireland and the United Kingdom can take part in some or all of the Schengen arrangements if the Schengen Member States and the government’s representative of the country in question vote unanimously in favor within the Council. Iceland and Norway, countries with no voting rights, can propose new measures or arrangements and also express their opinions on current developments.

Theoretical framework

Schimmelfennig and Sedelmeier’s external incentives model is relevant for analysing both the EU enlargement and Schengen Area membership. This is a rationalist bargaining model in which “the actors involved are assumed to be strategic utility-maximizers interested in the maximisation of their own power and welfare. In a bargaining process, they exchange information, threats and promises; its outcome depends on their relative bargaining power”.[5] According to the external incentives model, EU and Schengen external governance mainly follows a strategy of conditionality in which they set their own rules as conditions which the applicant countries have to satisfy in order to receive rewards.

This model makes use of what Grabbe[6] calls asymmetry of power and Keohane and Nye[7] asymmetrical interdependence. As far as the former is concerned it implies that there is an asymmetrical relationship between the applicant countries and the EU or Schengen “clubs”, which gives to the clubs more coercive routes of influence in the applicant countries’ domestic policy-making, therefore additional conditions. The latter approach, the asymmetrical interdependence, refers to the fact that the more asymmetry a country has in its favor, the stronger it is and therefore more resources and more advantage in influencing the outcome of an event.

Besides this (vertical) type of power asymmetry, there is also the case of different types of power between core states (horizontal), such as France and Germany, countries which proved to have greater power bargaining but also countries that came with initiatives and strategies into the Schengen cooperation. The stance of these countries with regards to migration policies and the Romanian-Bulgarian accession is what Putnam calls the two level game strategy. In the field of international negotiations, this strategy implies that “at the national level, domestic groups pursue their interests by pressuring the government to adopt favorable policies, and politicians seek power by constructing coalitions among those groups. At the international level, national governments seek to maximize their own ability to satisfy domestic pressures, while minimizing the adverse consequences of foreign developments”.[8]

Further, in order to understand how Schengen member states interact and decide when it comes to the area enlargement, this paper will use Tsebelis’[9] veto-players theory (VP) for explaining the Schengen member states’ behavior. The ‘veto players’ concept is an old one, dating back at least 2000 years. Tsebelis synthesises and formalises it. A veto player is an individual or collective actor who has to agree for the change of the legislative status quo. Tsebelis argues that having many veto players makes significant policy changes difficult or impossible. He also predicts that systems with a high number of veto players will pass few significant laws. The author considers two types of veto players: institutional (those officially named somewhere) and partisan (those whose veto arises from the system but are not one of the rules of the system). Some of these veto players, moreover, can present “take it or leave it” proposals to the other veto players. Tsebelis calls these “agenda setters”.

As mentioned above, in order for a new Schengen applicant country to be a full member there is the need for all the members’ agreement, however some countries have more veto-power than others. Therefore, in order to establish whether some actor is a VP or not, at least two questions have to be answered: 1) Does this actor have effective veto power? 2) How likely is this actor’s ideal point located in the pareto set of other (already identified) VPs (“absorption”)?

As Tsebelis claims, increasing the number of VPs tends to increase policy stability within a system, and it will never decrease it. This situation is reflected through the fact that in 2004 around ten new member states got Schengen membership (through membership applicant country becomes a veto-player), the collective decision making of that time veto-players being much easier than in the current Romanian-Bulgarian case when the number of veto-players almost doubled. If the ideal point of a new player is located in the pareto set of the existing players (the set of policies that could not be changed without leaving at least one player worse off), this player has no effect on policy stability – in Tsebelis’ terms, the player is “absorbed”. Via their effect on policy stability VPs are assumed to affect a number of important characteristics of political systems. High policy stability reduces the importance of players’ agenda-setting power because there are not many agreeable policies from which agenda-setters can choose. According to Tsebelis, policy stability may lead to government instability, in our case club instability, because as governments may resign if they cannot get anything done, Schengen member states can produce policy blocking and therefore cannot agree on changing the status quo of Bulgaria and Romania.

Analysis

According to Pascouau,[10] at the base of Schengen regime are principles such as solidarity (the ability to adopt common rules and to apply them correctly) and mutual trust, the certainty that the partner will apply the rules effectively. In addition, Pascouau claims that mutual trust is necessary in the common external borders monitoring. However, he claims that this implies that there is an “asymmetrical” affair because some countries’ land and sea borders are more exposed to major migrant influxes than others due to their geography. However, the trust and solidarity principles in the Schengen Area have been violated recently. One of the examples brought by Pascouau are the happenings in 2011, when as a result of the collapse of the dictatorship regimes in Egypt and Tunisia, 48,000 migrants had arrived in Lampedusa, Italy, by the end of August. The Italian government provided them with residence and travel permits in the Schengen Area. In these circumstances France asked for stronger border controls with Italy as a defense strategy to protect itself from the imminent “human tsunami”. Such incidents proved the weaknesses in mutual trust between the member states, not only between France and Italy but Schengen cooperation overall. National actions and European responses created the conditions to call the Schengen system and its philosophy into question. This proved that a partner can fail in its mission of external border control and endanger the public policy of its neighbors, affecting the area of free movement and taking the shape of the solid erosion of mutual trust. As Pascouau claims “the development of mutual mistrust among member states has de facto had a negative impact on Romanian and Bulgarian membership of the Schengen area, on representation agreements among member states over visa issuing procedures, and on the “Dublin” system relating to share out of responsibilities among member states as regards the distribution and treatment of asylum seekers’ demands”.[11]

The two level game strategy helps to explain the changing behavior of these countries with regards to their agreement on the Romanian Schengen membership: in 2010 French representatives in Romania stated that Romania has France’s agreement for its accession. In the same year Germany’s position was similar with the one stated by France: “We support Romania’s bid to join the Schengen Area, (…) Romania has already bravely sought to overhaul its judiciary and limit corruption,” said Merkel in one of her visits to Romania.[12] When it comes to analysing group choices, club choices in our case, Shepsle[13] claims that when one has an incentive to misrepresent their preferences by voting strategically, “a person might consider doing so if she or he could produce a more preferred final outcome”. In these circumstances it is worth questioning whether Germany or France could change an outcome by shifting their vote.

According to Tsebelis, among feasible outcomes (that is, the shared winset of outcomes which meet each veto player’s requirement of being superior to the status quo), agenda setters pick the outcome that they personally like most. From both countries’ EU accession process we can learn the fact that the core members such as Belgium, Netherlands, Luxembourg, Germany and France, are standing behind the Schengen idea and that the migration policy from the tiny economic size countries can be a reason for vetoing their membership.

Talking about migration Rechel points out one of the possible causes of veto players’ behavior. He claims that in the EU accession process the “fear of Roma migration to the “old” EU member states seems to have been a major driving force behind the increased concern for Roma. When Roma did migrate to the West, they often found little welcome and were sometimes summarily deported to their countries of origin. In the United Kingdom, reactions to the immigration of Roma from the Czech Republic were particularly hysterical.”[14] This quote and the following incidents such as Roma forced eviction and fingerprinting in Italy or France’s 2010 Roma repatriation program, emphasise once again that Roma migration from CEE countries creates a level of mistrust between members since Roma have been seen as sources of illegal trafficking, of exploitation of children for begging, of prostitution and crime.

As far as the asymmetrical interdependence is concerned, it allows for the clubs to set the rules of the game in the accession conditionality they have all the benefits to offer while countries such as Romania and Bulgaria with their tiny economic size have very little to offer and therefore little bargaining power, their desire to join is much greater than the wish of the member states to let them in. However only when the applicant countries get full membership, the power relationship between core and peripheral member states will reverse.

According to Pascouau, “it is equally crucial that public order and security issues remain the only reasons that can be claimed for reestablishing national border controls, and that no other reasons can be invoked, such as massive migrant influxes, which would lend themselves to all kinds of random interpretations.”[15] According to Pascouau, the refusal to accept the entry of Bulgaria and Romania into the Schengen area (even though the assessment report showed that both countries meet the requirements) is a sign of mistrust, “by using the issue of corruption, states have therefore shifted debate from the technical arena (evaluation of conditions required to eliminate internal border controls with Romania and Bulgaria) to the political arena”.[16] The final decision being in the hands of the member states and Council members. The hidden agenda provided by Pascouau is the fact that if Bulgaria enters the area of free movement, its territorial continuity with Greece and Turkey may pose similar threats to the other member states, as was the case with Italy and France. Another reason for the “delay” might be the lessons learned from Bulgaria’s and Romania’s EU membership in 2007, when both countries’ Roma ethnic minority migrated in western countries like Spain, Italy, and France and “disturbed” the countries’ public policies. Moreover, integration of Roma and adaptation to the host country living standards affected the reaction of certain states, such as France or Italy, to engage in costly, ineffective, and illegal policies like repatriation programs.

Conclusion

It can be concluded that the actor’s constellations involved in the accession preparations are very complex. Different parts of the EU as well as its institutions and member-states give different advice and signals, and different actors even within the same institution do as well. In this respect several studies show that the Romanian Bulgarian accession is “delayed” due to the mistrust between the veto-players demonstrating that a member state may have no confidence in the decision made by another.

Another reason is given by the increased number of actors because the threat comes from the random likelihood of an individual veto under unanimity, which increases exponentially as the EU enlarges. Recent reactions from France and Germany show that they both want to maintain a status quo that is closer to their interests than the proposed policies, such preferences being given by the expected huge migration from these countries of low skilled migrants and ethnic groups, especially Roma. Solidarity and mutual trust are the founding and structural elements of the Schengen area and therefore of the European migration policies.

The experienced mistrust phenomena showed the weaknesses of the relationship between the Schengen Area members but also between them and the Central Eastern European countries. However, it is hoped that the integrity of the area of free movement will be maintained thanks to the positions held by the European institutions, the interaction among which will decide on any improvements that may need to be made.

This piece expresses the opinions of the author only and does not necessarily reflect the position of the European Student Think Tank.

We are still looking for great writers to contribute to the European Student Think Tank!

List of references

[1]Andrew Moravcsik and Milada Anna Vachudova, “National Interests, State Power, and EU Enlargement,”East European Politics and Societies, 17 (2003), 51-52.

[2]Helmut Gaisbauer, “Evolving patterns of internal security cooperation: lessons learned from Schengen and Prüm laboratories”,European Security 22, no. 2, (2013), 188.

[3]European Commission, “Schengen, Borders & Visas” http://ec.europa.eu/dgs/home-affairs/what-we-do/policies/borders-and-visas/index_en.htm

[4]Romanian Ministry of Internal Affairs, “Schengen Romania” http://www.schengen.mai.gov.ro/

[5] Frank Schimmelfenniga and Ulrich Sedelmeier, “Governance by conditionality: EU rule transfer to the candidate countries of Central and Eastern Europe,” Journal of European Public Policy 11, no.4 (2004), 669.

[6]Heather Grabbe, “Europeanisation Goes East: Power and Uncertainty in the EU Accession Process,” In: Kevin Featherstone, Claudio M. Radaelli. The Politics of Europeanisation (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003).

[7]Robert O. Keohane and Joseph S. Nye“Power and Interdependence Revisited”. International Organization 41, no. 4, (1987), 725-753.

[8]Robert, D. Putnam, “Diplomacy and domestic politics: the logic of two-level games, “International Organization 42, (1988), 434.

[9]George Tsebelis, “Decision Making in Political Systems: Veto Players in Presidentialism, Parliamentarism, Multicameralism, and Multipartyism”.British Journal of Political Science 25, (1995), 289-326.

[10]Yves Pascouau, “Schengen and solidarity: the fragile balance between mutual trust and mistrust”. European Policy Center, (2012). Available online at: http://www.epc.eu/documents/uploads/pub_2784_schengen_and_solidarity.pdf(Accessed 20-05-2014).

[11]Yves Pascouau, “Schengen and solidarity: the fragile balance between mutual trust and mistrust”. European Policy Center, (2012), 2. Available online at: http://www.epc.eu/documents/uploads/pub_2784_schengen_and_solidarity.pdf(Accessed 20-05-2014).

[12]Irina Savu and Andra Timu, “Germany Will Back Romania for Schengen If Country Meets Tests, Merkel Says”. Bloomberg News, (2010). Available online at: http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2010-10-12/germany-will-back-romania-for-schengen-if-country-meets-tests-merkel-says.html(Accessed 20-05-2014).

[13]Kenneth A.Shepsle, Analyzing Politics: Rationality, Behavior, and Institutions. 2nd edition. (New York and London: W.W. Norton & Company, 2010).

[14]Bernd Rechel, “What Has Limited the EU’s Impact on Minority Rights in Accession Countries?” East European Politics and Societies 22, (2008), 182-183.

[15]Yves Pascouau, “Schengen and solidarity: the fragile balance between mutual trust and mistrust”. European Policy Center, (2012), 2. Available online at: http://www.epc.eu/documents/uploads/pub_2784_schengen_and_solidarity.pdf (Accessed 20-05-2014).

[16]Idem, 14.

Axa Schengen. Available online at: www.axa-schengen.com (Accessed 20-05-2014).

European Commission, “Schengen, Borders & Visas”. Available online at: http://ec.europa.eu/dgs/home-affairs/what-we-do/policies/borders-and-visas/index_en.htm (Accessed 20-05-2014).

Gaisbauer, Helmut. “Evolving patterns of internal security cooperation: lessons learned from Schengen and Prüm laboratories”, European Security 22, no. 2, (2013), 185-201.

George Tsebelis, “Decision Making in Political Systems: Veto Players in Presidentialism, Parliamentarism, Multicameralism, and Multipartyism”. British Journal of Political Science 25, (1995), 289-326.

Grabbe, Heather. “Europeanisation Goes East: Power and Uncertainty in the EU Accession Process,” In: Kevin Featherstone, Claudio M. Radaelli. The Politics of Europeanisation (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003).

Keohane Robert O. and Nye Joseph S. “Power and Interdependence Revisited”. International Organization 41, no. 4, (1987), 725-753.

Moravcsik Andrew and Vachudova Milada A. “National Interests, State Power, and EU Enlargement,” East European Politics and Societies, 17 (2003), 42-57.

Pascouau Yves. “Schengen and solidarity: the fragile balance between mutual trust and mistrust”. European Policy Center, (2012). Available online at: http://www.epc.eu/documents/uploads/pub_2784_schengen_and_solidarity.pdf (Accessed 20-05-2014).

Putnam, Robert, D. “Diplomacy and domestic politics: the logic of two-level games,” International Organization 42, (1988), 427-460.

Rechel, Bernd. “What Has Limited the EU’s Impact on Minority Rights in Accession Countries?” East European Politics and Societies 22, (2008), 171-191.

Romanian Minsitry of Internal Affairs, “Schengen Romania”. Available online at: http://www.schengen.mai.gov.ro/ (Accessed 20-05-2014).

Savu, Irina and Timu, Andra. “Germany Will Back Romania for Schengen If Country Meets Tests, Merkel Says”. Bloomberg News, (2010). Available online at: http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2010-10-12/germany-will-back-romania-for-schengen-if-country-meets-tests-merkel-says.html (Accessed 20-05-2014).

Schimmelfenniga Frank and Sedelmeier Ulrich. “Governance by conditionality: EU rule transfer to the candidate countries of Central and Eastern Europe,” Journal of European Public Policy 11, no.4 (2004), 669-687.

Shepsle Kenneth A. Analyzing Politics: Rationality, Behavior, and Institutions. 2ndedition. (New York and London: W.W. Norton & Company, 2010).

The geopolitical role of the Sahel: the influence of the EU and other Great Powers in the Malian crisis

The geopolitical role of the Sahel: the influence of the EU and other Great Powers in the Malian crisis  Is Nuclear Disarmament Still a Dream? The Third Meeting of State Parties in Perspective

Is Nuclear Disarmament Still a Dream? The Third Meeting of State Parties in Perspective  Strategic Saboteur: Hungary’s Entrenched Illiberalism and the Fracturing of EU Cohesion

Strategic Saboteur: Hungary’s Entrenched Illiberalism and the Fracturing of EU Cohesion  The invention of development: power, narrative, and the afterlife of Truman’s speech

The invention of development: power, narrative, and the afterlife of Truman’s speech