Hugo Decis graduated from a French classe préparatoire a few months ago. He is now a student of the Strategic and International Relations Institute (IRIS) located in Paris. He is also the newly elected Director of Communications of the Graduates of Democracy community.

Upon writing an article about a subject as misused and manipulated as what I would like to call ‘Burkini Gate’, it is important to keep one fact in mind: the burkini ban is in no way a national one, but rather a decision taken by less than thirty cities in France, out of 36,000. Therefore, the ‘Burkini Gate’ is not a controversy as important as various organisations are trying to make it out to be. Does this make the ‘Burkini Gate’ incident insignificant? Far from it: it highlights the divisions existing within both French society and, in a subtler way, the French government.

Those divisions within French society seem to be growing stronger by the day, considering that parts of the population are willing to reinterpret the republican concept of secularism. This concept, the result of nearly three centuries of political, social and philosophical reflection, is being used to ban certain types of clothing perceived as radical Islam’s latest manifestation, thus endangering two of our Republic’s cornerstones: individual freedoms and freedom of religion. It also highlights an identity crisis within the French Socialist Party. In addition to Manuel Valls calling the burkini a “political provocation” – thus sharing Nicolas Sarkozy’s views on the matter, which only proves that Hollande’s five-year term is an ideological disaster – a various number of ministers (like Bernard Cazeneuve) either tried to appease things or, like Najat Vallaud-Belkacem, criticised the ban. Such a lack of shared discipline, only six months before presidential elections and whilst political initiatives are multiplying on the government flanks, only shows that some parts of the left are willing to be infected by Sarkozy’s so called droite décomplexée, in order to win new elections. Then again, it’s not about debating the burkini’s nature but rather its interdiction’s rightfulness. To think that resorting to such a questionable tool will automatically create a change of mindset within the French Muslim communities is, for better or for worse, the French way of handling religious-tainted issues. The French way might differ from the Anglo-Saxon liberal approach, since it relies on yet another State’s intervention rather than promoting individual initiatives. That being said, such policies are yet to be proven effective in both the United Kingdom and the United States. Subsequently, in order to question the effectiveness of the French mayors’ decisions, one must focus on analysing the French government’s attempts at curbing the rise of Islam through arbitrary interdictions rather than relying on the inadequate Anglo-Saxon approach.

In the wake of the wars of independence which occurred in both Africa and Asia during the second half of the 20th century, a number of countries felt the need to battle against certain religious habits deemed as outdated, such as wearing the hijab, as a means of modernization. Their leaders, most of them being partisans of nationalist ideologies similar to 19th century European nationalism, were trying to achieve both state modernization and people’s emancipation. Thus, leaders such as Habib Bourguiba in Tunisia or Mustafa Kemal Ataturk in Turkey, decided to ban civil servants from wearing the veil and settled for advising their citizens not to wear it anymore. Others made it optional, such as Mohamad Zaher Shah, Afghanistan’s last king. A more radical approach was taken by Raza Shah Pahlavi, penultimate Iran’s Shah, who made it completely illegal to wear the hijab. Still, the impact of these policies was disappointing at best. Rather than encouraging the development of a long-lasting secular mindset, these hijab policies made it only easier for the Islamists to develop a rhetoric in which they appeared as martyrs of compulsory and undemocratic westernisation. In this light, it makes sense to doubt the effectiveness of the French mayors’ decision to ban the burkini in the context of the fight against radical Islam. Moreover, it is quite wrong to associate the burkini with this fight, considering that most Iranian mullahs, Saudi imams or Afghan Taliban would in no way tolerate the sight of a woman bathing alongside unfamiliar men, even at the beach.

How then can we explain the occurrence of such a unnecessary controversy in France? First, by considering the geopolitical context in which both Europe and France are living and second, by remembering that elections are to be organised in less than six months. For the second time in recent history the French Republic is watching two events collide: an international crisis (the rise of Islamism and terrorism on its soil) and an internal crisis (the election of a new president). Sadly, examining the last time those kind of events shared a same timespan only leads to an alarming conclusion: the eagerness to satisfy hurt public opinion, and to take good care of their image, causes politicians to prioritize the way they come across towards their rather than finding a relevant and effective solution. This modus operandi is for instance responsible for the massacre that occurred in Ouvéa in 1988, when the French army launched an assault against hostages-takers which were about to surrender to the authorities as they just aimed to make a statement, a few weeks before the elections. This disastrous logic is nonetheless what seems to be the French politicians’ strategy in the long run. Indeed, in order to prevail, women and men such as Marine le Pen, Manuel Valls or Nicolas Sarkozy are willing to appear as hommes providentiels – another sad, French pattern – even if it only means beating the war drums harder than the others.

And yet, there is another way, an honest way, that newspapers will not bother to write about. News outlets should recognize that the burkini, as sexist as it is – and it is, since it relies on a so-called moral duty to show modesty and reserve for women only – should nevertheless not be banned. A ban only damages individual freedoms and reinforces radical islamists’ rhetoric whilst preventing women from going to the beach – which is in fact a more daring way to defy religious obscurantism than what our so-called “feminist” leaders have been doing for the past months and years.

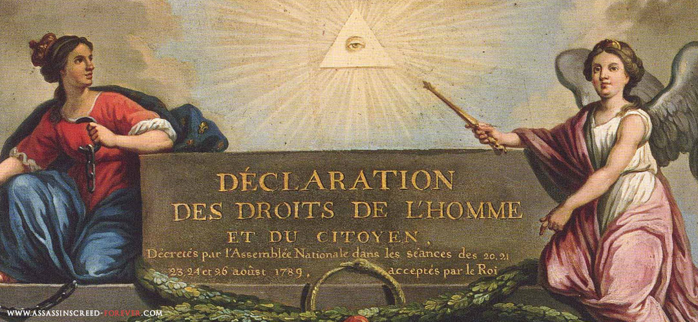

The mayors who decided to ban the burkini have provided various justifications for this decision. Some of them said that they aimed at defending French laïcité. They seem to have forgotten that our 1958 constitution quotes the 1789 Déclaration des Droits de l’Homme et du Citoyen in insisting on the fact that the Republic insures freedom of religion and guarantees the free exercise of religion, as long as they are not a threat to public order. Do those mayors really hope to prove that the burkini is endangering public order? Others may claim that they only want to protect women from religious obscurantism, which is at best doubtful since they never showed any desire to improve women’s living conditions before. Where were they when the right reduced funding for social programs and associations helping women gain easier access to contraception, STD’s prevention or abortion? Where were they when the right turned its back on the victims of domestic abuse? Where were they when the European Parliament tried to discuss the still existing salary gap between men and women but was not able to do it because the right voted against it? The fact that French politicians are willing to lie to get elected is nothing new. But it is simply terrifying to see so many citizens buy into the Front National feminist rhetoric whereas this party’s European representatives were only recently referring to abortion as a “weapon of mass destruction”.

Nevertheless, there are no redressers of wrong here. Various associations, eager to appear on television, indulged in the controversy, hoping to appear as both dispensers of justice and victims of secularism. Muslim citizens of France who felt hurt by the burkini ban decision might have hoped for a better lawyer than Marwan Muhammad. Muhammed, spokesman of the Collectif Contre l’Islamophobie en France (CCIF), indeed declared in 2011: “who has the right to say that France, in thirty or forty years, won’t be a Muslim country? Who as that right? No-one in this country has the right to take that away from us. No-one has the right to deny us the right to hope for a society faithful to Islam. No-one has the right in this country to define what is the French identity.” Until now, the CCIF was nothing but insignificant. From twenty-three releases published in the second half of 2011, it only published three releases in the first half of 2012. How can such a controversial association, whose members are known to be meeting radical imams and hateful preachers, be representing French Muslims? Sadly, for the common citizen who does not have entire days to dedicate to analyzing Burkini Gate, the fact that a man as despicable as Marwan Muhammad defends the right to wear the burkini immediately turned the fact of wearing it into a sign of radicalism. Therefore, the CCIF is in no way appeasing things nor defending Muslim women. It is, on the contrary, working towards dividing the society even more! It encourages tensions between communities and is not even trying to rationalise the republican debate. Its sole objective is both poisonous and irrational: to fuel hatred between French citizens, as this is its only way to appear on television. Subsequently, the first thing a politician willing to appease the situation should do would be to ignore the sleight of hand of such a dispensable association.

To add to this mess, the press, self-serving as ever, is at the same time setting things on fire and calling for firefighters, whilst ignoring Camus’ words on newspapers. Like many other thinkers and intellectuals, already in 1944 Camus criticized the media’s drift towards infotainment and the cult of immediate, terrific, disproportionate and dumb news. A few months before the Allies landed on the coasts of Normandy, Camus wrote: “How hard it is to be the first: one rushes on quaint details, appeals to the public’s sentimentality and willingness to be abused, howls alongside his readers, desperately trying to please him whereas he should only be enlightening him, all those actions being proof of the one’s despise for the people. And the media’s defence is well known: that’s what they want! And yet, that is rather what the public has been taught to want for the past twenty than what he really desires, which is utterly different.” And yet, one can only witness more and less well-known newspapers indulge in intellectual misery, ready to sacrifice the wiser way to inform the public upon the altar of cost-effectiveness; to crush the readers’ mind under hordes and hordes of articles somehow comparable to an artillery barrage; to bomb again and again the spirit’s walls. To see Le Monde, once one of France’s marvellous voices, taking part in the erection of this fortress of absurdities is nothing but another proof of the intellectual poorness of the paragons of the days of yore. Still we ought to be honest: the press is not the only one responsible. To click on an incomplete article, ill-written or resorting to unchecked facts, is by all means a dishonourable behaviour making you an accomplice of the great illusionist’s initiative. Camus, once again, had predicted it: “a society willing to be distracted by a dishonoured press and a thousand cynical entertainers […] is only heading towards slavery and that, despite the protests of the very ones who contributed to that degradation.” (CALIBAN, 1951)

What can we do, then, once it is clear that this controversy is nothing but the result of a society’s wounded pride? What can we do, once one understands the role played by cynical politicians and shameless media? The idealistic thing to do would be not to wait for the green light but to go and meet those women who, for whatever reason, decided to wear the burkini in order to understand their motives. It will always be honourable to make that effort, to build bridges, to challenge your own and other peoples’ mindset. Some women may admit that they are forced to wear it, and then your duty will be to help those individuals to get in touch with associations and institutions willing to help them stand for their rights. Others will say that they wear the burkini by their own choosing, even if it is directly linked to a social and cultural construction. Whatever your thoughts may be, you will have to respect that choice as long as it reflects the laws and constitution of the Republic. You will have to respect the fact that those burkini-wearing women show their desire to be part of our society by going to the beach in the first place. We should display tolerance at any time, without forgetting what we owe to the long fight for our secular society, in order to make sure we can truly enjoy our national motto: Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité, for all.

The French version of this article has previously been published on the ‘Graduates of Democracy’ website

- Articles and Blogs

- European Integration

- Geen categorie

- Global Politics

- law

- Migration

- radicalization

- Religion

- Uncategorized

- Women's Rights

Is the World Trade Organisation a Failure?

Is the World Trade Organisation a Failure?  Is EU citizenship for sale – or for keeps? A critical analysis of the CJEU’s Golden Visa ruling.

Is EU citizenship for sale – or for keeps? A critical analysis of the CJEU’s Golden Visa ruling.  The European Union in Space: From exploration and innovation to security and autonomy

The European Union in Space: From exploration and innovation to security and autonomy  The Rise of the Right: The Threat Right-Wing Extremism Poses to Women and Feminist Efforts in Germany

The Rise of the Right: The Threat Right-Wing Extremism Poses to Women and Feminist Efforts in Germany