Written by Aparajeya Shanker

No crisis in recent memory has called for greater solidarity, self discipline and sacrifice than the current COVID-19 crisis

Foreword from the author

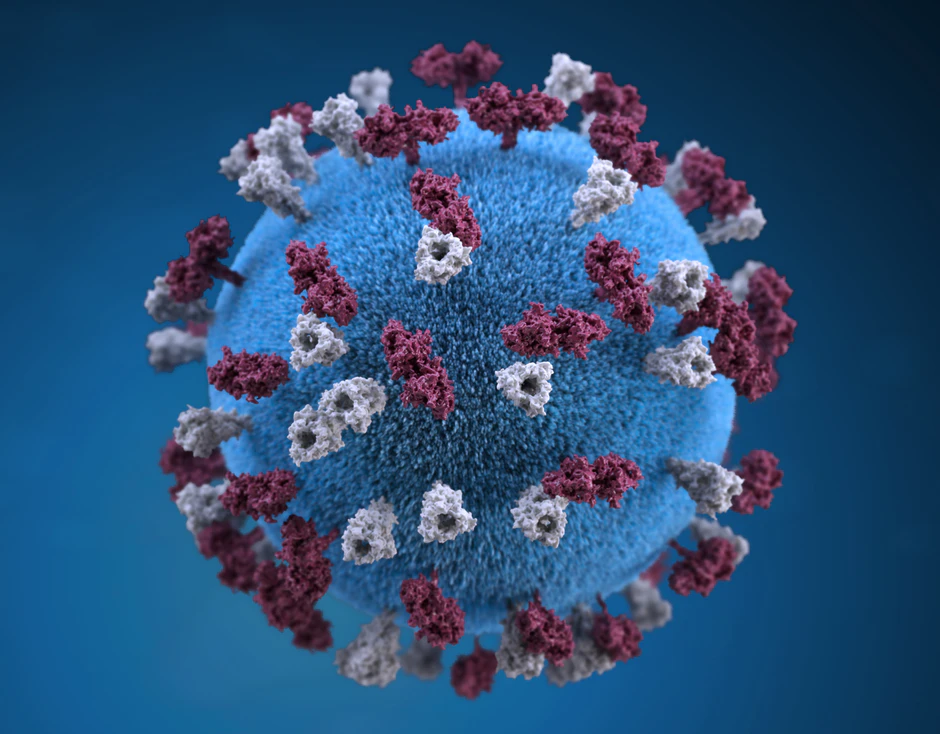

The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic requires no introduction. It has been declared a global pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) and responses from governments around the world have seen shutdowns, paralysis of healthcare systems and mass mobilization towards quarantine. The trajectory of this disease is still not understood because public health models do not have accurate data yet. It is, of course, common to see numbers flash on news channels and situation reports by the WHO, but there is very little in terms of contextualized data. One thing is certain, however, social distancing and quarantine are our only options in controlling this disease.

There are no current vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 the virus that causes the disease COVID-19. Treatment options for COVID-19 are limited. There are some potential antiviral medications, combined with anti-malarial drugs which show promise (Zhou et al, 2020) , but greater clinical trials are required before any treatment plan is globally adopted.

The pandemic has shown the fragility of healthcare systems around the world. Italy, a developed nation with resources, struggles to keep abreast of the pandemic, and the trajectory in Italy’s situation with COVID-19 are impossible to predict. The images in Italy of overcrowded hospitals, the ban on funerals, the shortage of masks and protective gear reveals that Italy is a case study of the resource intensive battle that embodies the fight against COVID-19.

With this seemingly cataclysmic view of the situation now, it is important to remind ourselves not to be paralyzed by fear and paranoia. While the situation is serious and will probably turn for the worse, it is important to remember that the fight against COVID-19 is not just in the laboratory or the hospitals, but a fight in which we are all involved. Quarantine, social distancing, stricter self-discipline are all the ways that we can fight this disease. Global cooperation is the way forward. Staying alert, but not paranoid is the way forward.

A major part of fighting a global pandemic in the 21st century is the constant battle against misinformation and paranoia. Reports on social media have been alarming. Empty supermarket shelves, hoarding of essential supplies, price-gouging, shortages in Personal Protective Equipment (PPE), and a rabid skepticism about the global response against COVID-19 aided by misinformation are causing ancillary problems in addition to the disease itself. The current challenge of COVID-19 is not just that it is a highly virulent disease with consequences that are fatal for the aged, but also that it tests our very values of democracy and our collective social cohesion. Protest against the Government is banned in many countries because of the ability of COVID-19 to spread through human-to-human contact, and this of course has implications for the values and rights we hold dear.

The fight against COVID-19 is far from over, and has only just begun. A global pandemic is one of the rare occasions where we must set aside our differences to work towards a common goal. We must balance our concerns and our rights towards self-determination while holding governments accountable. We must also remember that the COVID-19 pandemic calls upon us all to do the difficult thing, to actually make sacrifices for those who are sick and those for whom the disease will undoubtedly prove fatal. No other movement in recent history has called for greater solidarity and unity than the fight against COVID-19.

Introduction

COVID-19 is a global pandemic that began in Wuhan, China, in late December. Since January, the number of cases have spread around the world, tallying at over 300,000 cases, with at least 10,000 fatalities as of March 21st, 2020 (John Hopkins CSSE, 2020). Images and videos of overcrowded hospitals in Italy, silent streets around the world, and calls for quarantine are all well-known and familiar. It is important to know that the fight against COVID-19 has only just begun. The number of cases are constantly increasing in Europe and other countries, and there is no concrete sign that this disease’s trajectory is under control.

In order to further understand and contextualize the COVID-19 situation around the world, it is important that we discuss various facets of the disease. The global pandemic has brought with it economic losses, losses to business, culture, and a suspension of what it means to be human: the human touch itself (Hussain, 2020). COVID-19 has demonstrated the fragility of economic and healthcare systems around the world but has demonstrated a unique solidarity in the scientific world.

For the general public, however, the imperative here is to take personal and social responsibility. After all, the COVID-19 crisis in Italy has shown that no healthcare system, no matter how well equipped, can fight this pandemic alone. The complete involvement of all sections of society, across economic and social barriers, will aid in the fight against this disease. This article aims to address the specific concerns of the pandemic, in terms of the immediate action that the public can take, and also to arm the public with the appropriate context so that paranoia and fear do not grip the public.

Data and statistics, within context

The most recent numbers of COVID-19 state that there have been over 300,000 confirmed cases so far, and over 10,000 fatalities (John Hopkins CSSE, 2020). Of these total cases, 89,000 cases have recovered from COVID-19. The vast majority of cases in Europe are in Italy, with 41,000 cases since the start of the pandemic. Fatality rates currently vary, with some estimates placing the fatality rate between 2% to 5.7% (Baud et al, 2020).

Without context, the data is open to misinterpretation. Calculating a case fatality rate is an exercise in futility due to this being a current pandemic with constant changes in confirmed cases. Essentially, the fatality rate is calculated as a percentage of fatalities among people with known or confirmed cases. The primary concern in terms of calculating or measuring the seriousness of a pandemic in the terms of the fatality rate is that it is often not accurate because as a pandemic evolves and the number of confirmed infections increases, it can skew the fatality rate to reflect a higher or lower fatality rate. The secondary concern is the fact that there is a distinct shortage of testing kits available (Kuznia et al, 2020). Due to this, only those who show symptoms are being tested. It is resource intensive and wasteful to test everyone because this is not logistically possible.

A common criticism around the world is that not enough people are being tested. This is a valid concern and more tests should be made available. The WHO, in conjunction with governments around the world, is trying to certify more laboratories to provide testing (WHO, 2020). This is a process that requires stringent quality control.

The other concern with data currently is that it is not absolute and it is not static. These numbers are bound to change. As the past few months have demonstrated, current numbers are always bound to change and there are variables to be considered. Despite the numbers being shown to the general public that are endorsed by the WHO, the European Centre of Disease Control (ECDC), and the United States’ Center of Disease Control (CDC), it must be remembered that there is a dearth of concrete data. While numbers are important for getting an idea of the severity of the situation, all forms of data require the correct context (Ioannidis, 2020)

The data from the WHO states that those at greatest risk for serious complications requiring hospitalization are the elderly (over 65 years). This does not mean that those who are younger, or have chronic health concerns are not at risk for serious complications. The classification of disease severity into “Mild, Moderate, Severe” has been victim to misinterpretation by the young, as evidenced by the widespread disregard for social distancing seen in the United States. Date from the CDC, considering the number of known hospitalizations, stated 9% were aged ≥85 years, 36% were aged 65–84 years, 17% were aged 55–64 years, 18% were 45–54 years, and 20% were aged 20–44 years. This shows the seriousness of this disease across all age groups, except the very young (Razzaghi, 2020).

Global approaches to COVID-19

At the time of writing this article, the spread of COVID-19 is global with most of the world’s countries reporting COVID-19 cases. In total, 185 countries, states and territories have reported COVID-19. The number of cases, as described above, have only increased although some countries, like China, are reporting fewer new COVID-19 cases. The general approach in most countries has been that of containment, to track, contact-trace, and quarantine suspected cases and confirmed cases. However, Italy seems to be in the mitigation stage, with a complete lockdown of the country with increased focus on prioritising treatment and allocation of resources.

There is a caveat to any model adopted by a country that shows success in the fight against the pandemic. Not all countries have the same resources to enact the same general principle of complete isolation, shut-downs, and rigorous disinfection. South Korea and Singapore have been applauded by the United Nations (UN) for the constant testing and active measures taken to combat COVID-19.

The general principle of isolation and containment have been the working principle so far. However, there is growing concern around the world by people who compare the different responses to COVID-19 and ask why the same stringent measures placed in China are not used elsewhere. There is a comparison between the situation in Italy and other countries. Italy does serve as a case study in how difficult and resource intensive the battle against this pandemic is. Amid the fog of social media and the concerns of the public, the valuable lessons from Italy are being lost. Governmental inaction plays a part, for example, the United Kingdom initially felt that encouraging herd immunity would be a better idea than quarantine (Ghosh, 2020). However, this has changed in the past week with shutdowns, self-quarantine, and mobilization of “key workers” being the modus operandi (Public Health England, 2020). Much of this mismatch arises from multiple factors. One factor that plays a major role and bears repeating is the fact that the data gathered so far is simply not enough.

There must be greater investigation into why some countries report fewer cases than others. An informal analysis would indicate that constant testing, as is the case with South Korea, works, as do the intensive quarantine and disinfection protocols implemented in China. There is a missing link in this analysis. No study exists that can directly attribute only one single method of fighting against the pandemic. The only principle that does apply universally to this pandemic is the idea of social distancing and quarantine (Hellewell et al, 2020). This method, however, has implications for the global economy and severe implications for society at large. Global economic losses due to shutdowns and quarantine have implications in the foreseeable future and all response measures should be weighed keeping in mind the economy as much as public health (World Economic Forum, 2020). Although public health should take greater precedence and it is taking greater precedence in most countries, this pandemic will be far more difficult to combat within the context of economic collapse. Venezuela, a country facing economic and political unrest over the past year, is particularly vulnerable to the pandemic. The economic collapse and inflation have contributed to a complete lack of basic supplies in hospitals, the breakdown in the water supply system, and a lack of food in general, will only further compound the pandemic’s effects (Nugent, 2020). Venezuela should also serve as a case study in the effects of economic recession and the mortality of COVID-19.

Testing for COVID-19

The WHO recommends increased testing. Measures such as providing training, technical, and scientific support to countries around the globe have been implemented to aid in testing (WHO 2020). However, due to the increased demand, the number of test kits available now are limited and while testing everyone would be ideal, it is not possible at this stage (Schnirring, 2020). The European Centre for Disease Control (ECDC) has established clear guidelines for who to test first. The ECDC recommends testing to primarily the elderly with established underlying health conditions (cancer, cardiovascular disease, etc.), acute respiratory symptoms such as respiratory failure (characterized by severe shortness of breath and low oxygen content in the blood), and medical workers exposed to these patients (ECDC, 2020). This approach allows for better resource management until more testing kits are available. Countries around the world follow this general principle because it is important to allocate resources for the most vulnerable first.

There have been developments in regards to better and more rapid testing kits, but there is some scientific evidence to suggest that these tests may not be accurate. Testing for any disease is a process based on scientific evidence that involves demographic and statistical data. Testing for COVID-19 is a resource intensive process, involving Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) machines which amplify the genetic material present in the samples taken from patients, which then undergo specific genetic testing to confirm the presence of the SARS-CoV-2 (the causative virus responsible for COVID-19). This process requires training of medical staff and the establishment of infection and hygiene protocols, in addition to stringent quality control mechanisms.

Vulnerable populations

There are vulnerable populations around the world. The pandemic has shown us that the elderly and those with chronic medical conditions are especially vulnerable in times of crisis like this. An aspect of demographic changes that we have not considered is the effect of this crisis on the poor and vulnerable populations around the globe. Quarantine has suspended businesses, and while some countries have implemented economic packages for their workers, other countries with less stable economies have yet to implement economic packages serving the poor.

There are two other populations in Europe which require the immediate attention of the European Commission. The first are the Roma, the largest ethnic minority in Europe and the second are the refugees escaping the Middle East and Africa. Concerns surrounding the racial profiling of and discrimination against these populations have risen to the fore in the current crisis (Ouled, 2020). There is a specific concern as to how these two populations will access healthcare and whether quarantine procedures and national governmental support to these groups is adequate.

Refugees are not a uniquely European problem. Refugee camps around the world are facing a crisis due to the pandemic, especially when they face a lack of water and sanitation in refugee camps (Ahmed, 2020). Suspension of support services provided to refugees in Europe poses a risk to the status of refugees and their rights (Wallis, 2020). Further, it exposes them to greater risk of the pandemic. In context, this neglected population can compound the pandemic if further action is not taken within time (Ahmed, 2020).

Social implications of COVID-19

Through the course of this pandemic, from January onwards, there have been an uptick in racial discrimination against ethnic minorities. It began with racial abuse directed at people of Asian descent in Canada (Cecco, 2020). It continues now with Trump’s insistence on calling COVID-19 as the “Chinese Virus” (Little, 2020). Racist diatribes and racial attacks are unacceptable but continue to be shared widely on social media. Racial discrimination offline, such as racist attacks on people of Asian descent illustrate that the fight against COVID-19 is not only a battle against the disease, but also a fight against bigotry. The pandemic calls upon us to show greater solidarity and unity, across racial, age, and social lines.

An aspect of social distancing is the ban on protests requested by national governments around the world. The right to protest is a core principle of liberty and democracy. However, large gatherings of people increase the risk of human-to-human transmission of COVID-19. The greatest test of this pandemic is the challenge it poses to healthcare systems and to our shared democratic values. The ethical dilemma is to balance the right to protest with the prevention of the spread of COVID-19. This ethical dilemma is further complicated by misinformation about the severity of this disease. Misinformation ranges from cataclysmic projections of apocalyptic doom to the idea that this disease is not serious or is engineered as part of an authoritarian conspiracy. Conspiracy theories about the origin of this disease have spread like wildfire ever since January.

It is clear that the only way to contain this pandemic is through social distancing and quarantine. However, many protests continue around the globe with no intention of suspension. In India, some protestors have tested positive for COVID-19 (Outlook India, 2020), and despite this, the protests continue. The challenge globally is to measure our democratic values with the threat of the pandemic itself. Measures should be taken to ensure that although we face a global crisis, we should not forget our democratic values. This, however, does not mean an endorsement of large gatherings, but an appeal to protests around the world to suspend their protests until this pandemic is under control.

Religious meetings and gatherings have not been suspended in some countries either. While religious beliefs are a source of comfort, it must be remembered that religious gatherings pose a very high risk of amplifying human-to-human transmission as was observed with Patient 31 in South Korea, who spread the disease during a church meeting (BBC, 2020). Many religious groups have not suspended their activities, and some have. All religious gatherings should be suspended in light of the pandemic, and trust must be placed on the scientific and public health measures put in place to combat COVID-19.

Status of therapeutics

The search for appropriate therapy against COVID-19 has seen an acceleration in the past few weeks. Considering the nature of this crisis, it is understandable that the search for medication and vaccines be given the priority it deserves. Some antiviral medications, combined with anti-malarial drugs, have shown some promise (remdesevir and hydroxychloroquine) (Zhou et al, 2020). The recommendation for using hydroxychloroquine is based on the improvement on CAT Scan (CT) images and reduction of fever. This drug was also used during the Ebola outbreak. The concern here is that there have been no clinical trials to test the efficacy of this combination. While this combination is approved in China; reproducible, peer-reviewed, stringent research is of great necessity.

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) is the safest way to prevent transmission in doctors and medical staff. Unfortunately, a global shortage of PPE, probably accelerated by the panic buying of masks and gloves has endangered frontline medical staff. The WHO is currently working on supply chain management to ensure that masks, respirators and gloves can be supplied to the countries that most need it.

The current management of COVID-19 in severe cases remains largely supportive. Oxygen therapy and ventilator support are the only ways to provide supportive treatment in the absence of evidence-based clinical medication (WHO, 2020). It must be noted that no vaccine or antiviral medication for SARS-CoV-1 (responsible for the SARS outbreak in 2003) exists. Most coronaviruses cause only mild, upper respiratory tract infections and SARS-CoV-2 (responsible for COVID-19) is relatively new, even in terms of its evolutionary and phylogenetic history (Li et al, 2020).

Currently, 20 vaccines are being investigated around the world with the help of the WHO’s R&D blueprint. However, the earliest possible date for a safe and effective vaccine is spring 2021. Until then, non-pharmaceutical interventions such as quarantine, social distancing, and containment are the most effective methods of pandemic control. Due optimism is understandable, however, the most effective approach is to comply with the evidence present now: that COVID-19 is best prevented through stringent social distancing and quarantine.

Future considerations

COVID-19 has given us valuable lessons in healthcare. Primarily, it has exposed the vulnerability and fragility of healthcare systems around the world. It has also shown that global cooperation is vital to the scientific management of disease and public health crises. It must be noted that this is not the end of the pandemic, but the beginning and strategies will evolve as further data is made available and considered. The fight lies ahead.

It is important to remember the maxim of “Alert, not Paranoid” when dealing with COVID-19. This pandemic is the first in history where evidence and rapid transmission of scientific and technical guidance are available (WHO, 2020), and the first where a unified response is possible. COVID-19 has also shown that while information can be disseminated with ease, there is a great potential for misinformation to spread. The current pandemic is not only a healthcare effort, but also multifaceted with implications on society and economics. Solidarity across countries is as important as is assuming personal and social responsibility in combating this pandemic.

Healthcare systems around the world will need to change to be better prepared to deal with crises like this, where large patient volumes have the capacity of overwhelming even the most well-developed and well-funded healthcare systems. The concern for Europe must be to unify and standardize all healthcare systems within the European Union to facilitate a more efficient healthcare response. Although each nation faces unique challenges in crises like these, the value of standardizing responses and evolving better healthcare systems cannot be understated. Greater funding for healthcare is a priority now and moving forward. Healthcare systems should be prioritized to ensure that responses across the EU are standardized and unified.

The source of COVID-19 was traced to a seafood and exotic wildlife wet market in Wuhan, China. It is time to recognize the implications and importance of enforcing wildlife trade restrictions and to also enforce hygiene and sanitation standards around the world. Although hindsight is gifted with clarity, it is prudent to suggest that this pandemic could have been prevented.

The fight against COVID-19 will not end with a fall in new cases. The next challenge will be to ensure an equitable distribution of vaccines, improvement in healthcare, and an increased public awareness campaign of the importance of hygienic and sanitation requirements. The challenge with vaccines is well-understood, with vaccine confidence rates falling across the EU and the world. The challenges due to misinformation and propaganda need to be confronted with a global, scientific and evidence based approach and will be the greatest challenge yet.

Conclusion

The global effects of COVID-19 have only just begun. The pandemic is in its early stages and while this is a cause for concern, it is not cause for paranoia. Paranoia, reflected by the increase in panic buying and the spread of misinformation, risks further social and healthcare collapse. Precautions such as good hand hygiene, social distancing, and quarantine are the only evidence based ways to stop the spread of COVID-19. It is the duty of every person to participate in the mobilization against COVID-19 by breaking the chain of transmission. Low reported cases should not be a cause for complacency but for resolute maintenance of containment protocols. Lower numbers of new reported cases in China, while admirable, should not be the cause of lowering concern and relaxing the stringent requirements for quarantine.

It is important to be alert to the challenges of COVID-19, to be alert to the challenges faced by the vulnerable and elderly, but paranoia is not the way. The maxim for fighting COVID-19 is “Alert, not Paranoid.”

References

Ahmed, 2020,

The Guardian World’s most vulnerable in third wave for COVID19

Baud, David

The Lancet: Real estimates of mortality following COVID-19 infection

12th March, 2020

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30195-X

BBC 2020 Coronavirus: South Korea church leader apologises for virus spread

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-51701039

Cecco, The Guardian Canada Chinese Community battles racist backlash

European Center for Disease Control

https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/covid19_-_eu_recommendations_on_testing_strategies_v2.pdf

Ghosh, Pallab

BBC News Coronavirus: Some scientists say UK virus strategy is ‘risking lives’

https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-51892402

Hellewell et al

The Lancet Feasibility of controlling COVID-19 outbreaks by isolation of cases and contacts

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/langlo/article/PIIS2214-109X(20)30074-7/fulltext

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30074-7

Hussain, Samira

BBC News :Global stock markets plunge on coronavirus fears

https://www.bbc.com/news/business-51612520

Ioannidis

Statnews : A fiasco in the making? As the coronavirus pandemic takes hold, we are making decisions without reliable data

John Hopkins CSSE

https://gisanddata.maps.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html#/bda7594740fd40299423467b48e9ecf6

Kuznia R, Devine C, Drew G

CNN: Severe shortages of swabs and other supplies hamper coronavirus testing

https://edition.cnn.com/2020/03/18/us/coronovirus-testing-supply-shortages-invs/index.html

Li et al, 2020

Journal of Medical Virology Evolutionary history, potential intermediate animal host, and cross-species analyses of SARS-CoV-2.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.25731

Little, Becky Time Trump’s ‘Chinese’ Virus Is Part of a Long History of Blaming Other Countries for Disease.

https://time.com/5807376/virus-name-foreign-history/

Nugent, Ciara Time Could the Coronavirus Topple Nicolas Maduro’s Regime in Venezuela?

https://time.com/5807142/venezuela-maduro-coronavirus-oil/

Ouled, Youssef 2020, Racism in a pandemic

https://www.liberties.eu/en/news/racism-in-a-pandemic/18949

Outlook India

Corona positive case in Shaheen Bagh sends protesters into tizzy

https://www.outlookindia.com/newsscroll/corona-positive-case-in-shaheen-bagh-sends-protesters-into-tizzy/1775806

Public Health England Gov.uk 2020

Razzaghi, Hilda

Center for Disease Control and Prevention

https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6912e2.htm

Schnirring, Lisa

Centre for infectious disease research and policy

Wallis, Emma InfoMigrants.com

WHO EVENTS https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/events-as-they-happen

WHO Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) technical guidance: Laboratory testing for 2019-nCoV in humans

WHO 2020 Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection when novel coronavirus (nCoV) infection is suspected

https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance/patient-management

WHO WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 – 11 March 2020

World Economic Forum The IMF explains the economic lessons from China’s fight against coronavirus

https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/03/imf-economic-lessons-from-china-fight-against-coronavirus

Zhou et al

Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy COVID-19: a recommendation to examine the effect of hydroxychloroquine in preventing infection and progression

https://academic.oup.com/jac/advance-article/doi/10.1093/jac/dkaa114/5810487?searchresult=1

A Catastrophe for Generations: The Production of Debility during the Genocide in Gaza

A Catastrophe for Generations: The Production of Debility during the Genocide in Gaza  Unity and Disunity in EU Diplomacy: Why Speaking with One Voice Remains Difficult

Unity and Disunity in EU Diplomacy: Why Speaking with One Voice Remains Difficult  Sharing the Costs of Climate Ambition: Rethinking Justice in the EU’s CBAM

Sharing the Costs of Climate Ambition: Rethinking Justice in the EU’s CBAM  The ’Ndrangheta’s Infiltration and Threat to European Institutions

The ’Ndrangheta’s Infiltration and Threat to European Institutions